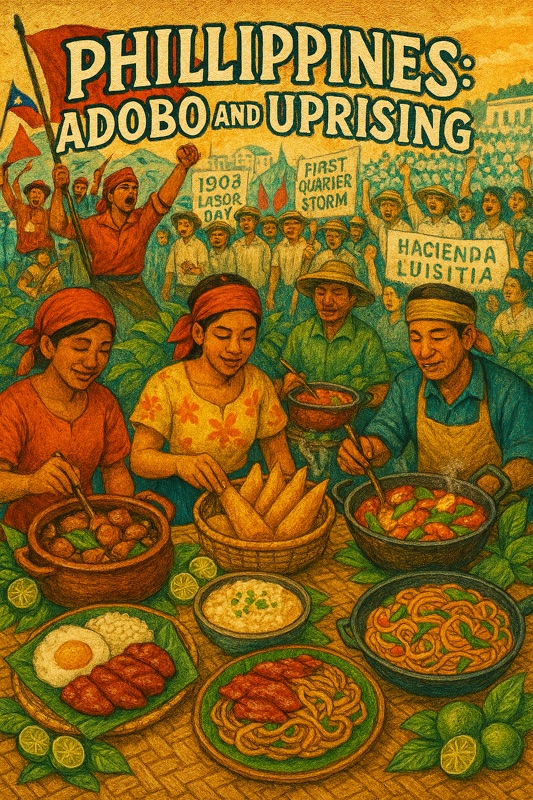

Philippines: Adobo and Uprising

Philippines: Adobo and Uprising

The Philippines has always been a nation forged in contradiction. An archipelago of more than 7,000 islands scattered across the Pacific, it has been a meeting point for traders, a prize for empires, and a crucible for revolutions. Long before the first European sails broke the horizon, there were thriving kingdoms and sultanates, Luzon’s maritime trade with China and Japan, Mindanao’s Islamic polities linked to Borneo and the Malay world, the Visayas’ warrior-chiefdoms sending out balangay fleets. These islands were not isolated, they were part of a vast, shifting web of commerce, culture, and power.

Then came Spain in 1521, bringing the cross and the cannon. The next 333 years would see Manila galleons hauling silver from the Americas and silk from China, with the islands themselves treated less as a nation than as a pit stop for empire. Catholicism took root alongside forced labor and land dispossession. Revolts flared, in Ilocos, Pampanga, Bohol, Mindanao. only to be met with the friar’s sermon and the soldier’s musket. Churches rose over mass graves. Sugar plantations spread where forests once stood. And yet, in kitchens from the poorest barrios to the convents themselves, Filipino cooking quietly evolved, blending native ingredients with Spanish methods, adopting, adapting, and resisting through the plate.

In 1896, the Katipunan lit the match. Andres Bonifacio’s revolutionaries, Katipuneros, fought for a free Philippines, fed in no small part by pots of adobo, rice, and coffee. Spain fell, but freedom proved short-lived. The Americans arrived in 1898 with public schools and machine guns, promising democracy while slaughtering tens of thousands in the Philippine–American War. It was a campaign often justified by American politicians and missionaries as a divine mission to "Christianize" the islands, an absurd claim given the Philippines had been a deeply Catholic nation for over 300 years.They reorganized land ownership to favor elites, built roads to extract resources, and taught English while quietly reinforcing class divisions. Yet they also brought soy sauce, canned goods, and bread-making, which Filipinos, ever resourceful, folded into their kitchens.

The Japanese came in 1941 with dreams of a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” What they got instead was an island-wide guerrilla war, one fed on root crops, dried fish, and whatever could be grown, scavenged, or stolen under occupation. By war’s end, the Philippines was in ruins. Independence in 1946 was less a clean break than a handover from one patron to another, with U.S. bases on the soil and U.S.-backed politicians in power.

Postwar decades brought the promise of progress but also the weight of inequality. Peasant uprisings like the Huk Rebellion, militant labor movements, and student radicals of the 1960s and ’70s kept the spirit of resistance alive. Ferdinand Marcos’ martial law (1972–1981) turned the country into a prison for dissenters and a playground for cronies, but also, ironically, spurred the underground networks that would later topple him.

Through it all, food was both sustenance and statement. Vinegar kept meat from spoiling when refrigeration was a luxury. Rice stretched the smallest portions to feed many mouths. Soy sauce could give depth to even the toughest cuts. These weren’t just flavors, they were strategies for survival, forged in scarcity and sharpened by necessity.

This post is about six dishes. Not the ones plated for hotel buffets or airbrushed for glossy cookbooks, but the ones that have marched with the people, filled their bellies, and fueled their fights. Chicken Adobo, the unofficial national dish and the rebel’s rations during the Katipunan’s uprising. Lumpia, fried crisp for the workers who gathered at the 1903 Labor Day rally in Manila, the first in Asia. Arroz Caldo, steaming bowls carried into meetings of the 1930s Sakdalista peasant movement. Sinigang; its sourness a perfect match for the anger that boiled over during the First Quarter Storm. Tosilog; fried on the edges of the barricades during the People Power Revolution and remembered at Mendiola. Pancit Canton; cheap, cold, and eaten on the picket lines during the bloody 2004 Hacienda Luisita strike.

The Philippines’ history is not a straight march to freedom, it’s a cycle of repression and resistance, of power hoarded and people rising. And in that cycle, food has always been there: in the pot, in the hand, in the protest, in the memory.

So crack an egg, set your rice to steam, and ready your broth to sour, because this is the story of the Philippines told not by presidents or generals, but by its working-class kitchens.

Chicken Adobo: Revolution in a Clay Pot

Chicken Adobo is more than the Philippines’ most beloved dish, it’s a survival strategy that predates the nation itself. Its origins stretch back to the pre-colonial barangays, long before Magellan’s cross touched Cebu’s shores in 1521. In those days, Austronesian seafarers preserved meat and fish in tuba (palm vinegar) and salt, an age-old technique that kept food edible during long voyages and in the humid, insect-rich tropics. The word adobo comes later, a Spanish label from adobar, meaning “to marinate,” applied by the colonizers who recognized a familiar tang in an unfamiliar land. The native method endured because it worked, vinegar slowed spoilage, salt cured, and garlic kept pests and illness at bay.

Over centuries, the formula evolved, incorporating Chinese-traded soy sauce into the marinade alongside the ever-present vinegar. Black peppercorns, laurel leaves, and sometimes coconut milk joined the pot. It was flexible, forgiving; pork, chicken, squid, vegetables; whatever was on hand could be stewed into sustenance. And most importantly, it was portable: a pot of adobo could be carried for days without turning rancid, feeding farmers in the fields, fisherfolk at sea, and, when the time came, revolutionaries in the hills.

By the late 19th century, the Philippines was a colony under the heavy boot of Spain. Three centuries of friar rule had carved the land into vast haciendas owned by Spanish religious orders and loyal principalia. The indios, peasants, laborers, and workers, paid tribute, endured forced labor, and had little hope of advancement. But change was simmering, and like a slow stew, it was gathering strength.

It began with ideas. In 1887, José Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere and later El Filibusterismo exposed the cruelty of the friars and the hypocrisy of colonial rule. These novels were banned, but they passed from hand to hand, read aloud in candlelit gatherings. The ilustrados, educated Filipinos, many schooled in Europe, dreamed of reform: equality before the law, secular education, representation in the Spanish Cortes.

But beneath this polite reformism, another current surged, one with no patience for Spain’s permission.

In 1892, Andrés Bonifacio, a warehouse clerk and radical thinker, founded the Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan, the Katipunan. It was a secret society of workers, farmers, artisans, and teachers sworn to fight for complete independence. They met in back rooms, warehouses, and bamboo huts. Their meetings often ended in communal meals, bowls of rice, dried fish, and, when fortune allowed, clay pots of adobo. In this stew, there was both nourishment and defiance: a dish born before Spain, now fueling the fight to outlast it.

When the Spanish authorities discovered the Katipunan in August 1896, there was no more time for secrecy. On August 23, in a grassy barrio called Pugad Lawin, Bonifacio and hundreds of Katipuneros tore up their cedulas, residence certificates and symbols of subjugation, and cried for independence. It was the spark that lit the Philippine Revolution.

Rebel camps sprang up in forests and mountains. Supplies were scarce. Meals had to be simple, keep without refrigeration, and feed many. Adobo was ideal: its vinegar and salt kept meat edible for days, and its ingredients, garlic, pepper, bay, were easy to forage or trade for. Cooking it in clay pots over open fires, the Katipuneros ate from the same vessel they cooked in, passing spoons from hand to hand. Each bite was a reminder of what they were fighting for: a life no longer dictated by Spain’s table.

The revolution was fractious. Bonifacio clashed with Emilio Aguinaldo, a Cavite leader with military skill but political ambition. Bonifacio would be executed by his own comrades, yet the cause pressed on. By June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo stood on a balcony in Kawit, Cavite, and declared independence from Spain. But even as the flag waved, American warships sat in Manila Bay, ready to claim the islands for themselves. The promise of an American alliance had been a cruel fiction, one of many perpetuated by the new colonizers who justified their war by claiming a need to “civilize and Christianize” the already-Catholic nation. Within a year, the Philippine–American War would erupt, and the struggle for true independence would begin again.

But that is another meal.

Adobo requires patience. But, it’s quite delicious. Its tangy flavor may just be your favorite way to eat chicken by the end.

Chicken Adobo

Description: A savory, tangy Filipino stew with chicken (or pork) braised in soy sauce, vinegar, garlic, and spices.

Ingredients:

- 2 lbs (1 kg) chicken thighs or drumsticks, bone-in

- ½ cup soy sauce

- ½ cup white vinegar

- 1 cup water

- 1 head garlic, minced

- 1 medium onion, sliced

- 2 bay leaves

- 1 tsp whole black peppercorns

- 2 tbsp cooking oil

- Optional: 1 tsp sugar, 2 potatoes (cubed)

Instructions:

- Marinate: In a bowl, combine chicken, soy sauce, half the garlic, and peppercorns. Marinate for 30 minutes (optional).

- Sauté: Heat oil in a large pot over medium heat. Sauté remaining garlic and onion until fragrant.

- Brown Chicken: Add chicken (reserve marinade) and cook until lightly browned, about 5 minutes.

- Simmer: Pour in marinade, vinegar, water, and bay leaves. Bring to a boil, then lower heat and simmer for 30-40 minutes, uncovered, until chicken is tender. Add potatoes halfway if using.

- Adjust: Taste and add sugar if desired. Simmer 5 more minutes.

- Serve: Serve hot with steamed rice.

Notes: Do not stir after adding vinegar until it boils to avoid a raw vinegar taste.

Lumpia: Rolls of Resistance

Lumpia is a dish of many hands, hands that chop, season, roll, and fry, hands that pass plates around birthdays, wakes, and rallies alike. It’s one of the Philippines’ most iconic party foods, but beneath the crisp shell lies a story of migration, adaptation, and solidarity.

Its ancestry reaches back centuries to run bing, the fresh spring rolls of Fujian Province, carried across the South China Sea by Chinese traders long before the Spanish conquest. In bustling precolonial ports like Manila, Cebu, and Iloilo, these traders settled, married into local families, and folded their culinary traditions into the archipelago’s own. Over time, the roll transformed, filled with local vegetables, pork, shrimp, or mung bean sprouts, sometimes served fresh (lumpiang sariwa), sometimes fried (lumpiang prito). Vinegar dips mirrored ancient preservation techniques, while wrappers evolved from rice flour crepes to paper-thin wheat sheets.

By the 19th century, lumpia was at once street food, lunch for schoolchildren, and appetizers for the drinking table, a dish that could be both humble and celebratory. What never changed was its communal nature: lumpia-making was an assembly line of conversation and cooperation. It was food that came into being through collective effort, an edible metaphor for organizing.

And in 1903, organizing was in the air.

The Philippine Revolution (1896–1898) had driven Spain from the islands, but the victory was stolen. Under the Treaty of Paris, Spain sold the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. Filipino revolutionaries, who had declared independence in Kawit, Cavite, found themselves facing a new imperial army. The Philippine–American War (1899–1902) was brutal, marked by massacres, scorched-earth campaigns, and famine.

By 1902, open resistance was crushed in most regions. The Americans shifted from military occupation to “civil government,” but it was civil in name only. They rebuilt infrastructure for export economies, favoring U.S.-aligned elites. New corporate plantations, sugar mills, and logging operations demanded cheap, docile labor. Wage disputes were met with firings, strikes with arrests.

Into this tense new order stepped Isabelo de los Reyes, a journalist, folklorist, and revolutionary intellectual who had already been imprisoned by the Spanish for sedition. Returning from exile, de los Reyes turned his gaze from nationalist politics to class struggle. In 1902, he co-founded the Unión Obrera Democrática Filipina (UODF), the first major labor federation in the country. It brought together dockworkers, printers, seamstresses, carpenters, cigar rollers, and more, uniting trades that had never before shared a common platform.

Their demands were radical for the time: eight-hour workdays, safer conditions, higher pay, and, crucially, Philippine independence. They understood that true sovereignty wasn’t just about flags and anthems, but about the dignity of the worker.

May 1, 1903, was their proving ground. Inspired by the growing global recognition of International Workers’ Day, the UODF called for a mass rally in Manila. Flyers rolled off union-owned presses, messages passed quietly through loading docks, and word-of-mouth carried the call into weaving rooms, print shops, and market stalls.

That morning, the streets swelled. Workers poured out of Tondo, Santa Cruz, and Binondo, marching with red banners painted in Spanish, Tagalog, and English. Chants echoed off corrugated roofs and stone façades: ¡Viva la independencia! Mabuhay ang manggagawa!

And like any Filipino gathering, whether fiesta or protest, there was food. Women woke before dawn to fry batch after batch of lumpia, stacking them in banana-leaf-lined baskets. Street vendors set up makeshift stalls along the procession route, their oil crackling as marchers stopped for a bite. Unionists on break leaned against walls, licking vinegar from their fingers between speeches. Children clutched rolls in one hand and tiny red flags in the other. Lumpia, inexpensive and easy to carry, fueled the rally as much as rhetoric did.

Governor-General William Howard Taft saw none of the joy in this gathering. To him, it was a dangerous show of defiance. By afternoon, constabulary forces moved in, dispersing the crowd and arresting UODF leaders, including Hermenegildo Cruz. Taft branded them anarchists; newspapers loyal to the colonial government painted them as rabble.

The UODF was broken within a year, but the spark it lit did not fade. The 1903 rally remains one of the largest labor demonstrations in Philippine history, and May 1 would later be enshrined as Labor Day, one of the rare victories wrested from colonial hands.

In the decades that followed, lumpia would reappear in strike kitchens, union halls, and protest marches. It was rolled in clandestine meetings under Martial Law, sold to raise funds for jeepney drivers’ strikes, and passed around at rallies demanding wage increases and land reform. It fed not only the stomach but the spirit, embodying the same principle as the movements it nourished: that many hands, working together, can create something worth fighting for.

And soon, another movement, rooted not in the factories but in the fields, would rise to demand the most fundamental resource of all: land.

Make sure you make these for a crowd! The recipe yields alot.

Lumpia (Filipino Spring Rolls)

Description: Crispy spring rolls filled with meat and vegetables, served with a sweet chili or vinegar dipping sauce.

Ingredients:

- 1 lb (500g) ground pork

- 1 cup shrimp, chopped (optional)

- 1 medium carrot, julienned

- 1 cup cabbage, shredded

- ½ cup green beans, finely chopped

- 1 small onion, finely chopped

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- 2 tbsp soy sauce

- 1 tsp fish sauce

- Salt and pepper to taste

- 20-25 lumpia wrappers

- 1 egg, beaten (for sealing)

- Cooking oil for frying

- Dipping sauce: Mix ¼ cup vinegar, 1 tsp minced garlic, 1 tsp soy sauce, and 1 small chili (or sweet chili sauce)

Instructions:

- Make Filling: In a large bowl, mix ground pork, shrimp (if using), carrot, cabbage, green beans, onion, garlic, soy sauce, fish sauce, salt, and pepper.

- Wrap: Place 2 tbsp of filling on a lumpia wrapper. Fold the bottom over the filling, tuck in the sides, and roll tightly. Seal the edge with beaten egg.

- Fry: Heat 2 inches of oil in a deep pan to 350°F (175°C). Fry lumpia in batches for 3-5 minutes until golden brown and crispy. Drain on paper towels.

- Serve: Serve hot with vinegar dipping sauce or sweet chili sauce.

Notes: For lumpiang shanghai, make smaller rolls and use only meat and minimal vegetables. Freeze uncooked lumpia for later use.

Arroz Caldo: Warmth in the Barricades

Arroz Caldo is not a dish of luxury. It will not dazzle a guest list or gild a banquet table. It’s built to sustain, not impress, ginger-scented, softly simmered, thick with starch, salt, and the steam of survival. It carries the Spanish word arroz for rice, but its soul is older, closer to the Chinese jūk and chok brought centuries earlier by traders who carried more recipes than silver. Over time, Filipinos married the two traditions, adding fish sauce, garlic, calamansi, and when luck allowed, a boiled egg or chicken wing for strength.

It became the dish for times of strain: when the skies opened and the fields turned to mud; when sickness swept through a household; when payday was still two sunsets away. It was a meal that could stretch itself thin but still fill many bowls, each ladle not just nourishment but an act of care.

In the 1930s, the Philippines was hungry for more than food.

The country was in the awkward grip of the Tydings–McDuffie Act’s promise: “eventual independence” under a 10-year Commonwealth transition. It was a pledge that Washington and Manila politicians alike touted as a step toward freedom. But in the provinces, where tenant farmers bent over rice paddies from before dawn until the herons came home, it felt like a far-off banquet to which they’d never be invited.

American sugar barons and Filipino landlords still controlled the countryside. Land taxes bit deep into meager earnings. The much-talked-about land reform never reached beyond speeches and paper plans. In barrios and barangays, the same families that had worked haciendas under Spain were now working them for U.S.-aligned elites or Filipino politicians in tailored barong Tagalog.

Into this discontent stepped Benigno Ramos, a former government translator who swapped his desk for a pen dipped in fire. Ramos launched the Sakdal newspaper in 1930, naming it for the Tagalog word sakdal, “to accuse.” He accused President Manuel Quezon and the political elite of betraying the masses, replacing American masters with Filipino ones in fine clothes. Ramos called for immediate independence, the redistribution of land to those who tilled it, the abolition of taxes on the poor, and the removal of U.S. military bases. His words did not echo in the marble halls of Manila, they landed in bamboo huts and carabao sheds, carried in rolled-up newspapers and memorized in dim light.

The movement grew in rice fields and fishing villages, fueled by a quiet ritual: steaming pots of Arroz Caldo. Organizers served it before predawn meetings so no one debated on an empty stomach. Mothers ladled it out to children while whispering that their fathers would be gone that day to “help Ramos.” In makeshift kitchens, young men stirred cauldrons of rice and ginger over wood fires before marching out to paint Sakdal slogans on town walls. It was humble fuel for dangerous work, a kind of edible courage.

On May 2, 1935, that courage boiled over.

In coordinated uprisings across Laguna, Cavite, Bulacan, and other provinces, thousands of Sakdalistas, many barefoot, armed only with bolos, bamboo spears, or borrowed rifles, seized municipal halls, cut telegraph lines, and hoisted the red-and-white Sakdal flag. It was not an elite’s coup; it was the countryside on its feet, farmers and fishermen declaring they would wait no longer.

The Philippine Constabulary, trained and equipped by the Americans, moved fast. Within days, machine guns and volleys of rifle fire shattered the rebellion. More than 100 were killed, hundreds more imprisoned. Ramos escaped into exile in Japan, where his movement withered without its base.

The revolt failed in arms, but not in memory. For those who had shared its cause, the taste of gingered rice still carried the echo of those days, of whispered plans over the pot, of bowls passed down the line before dawn, of men and women who believed that freedom without bread was no freedom at all. Arroz Caldo remained in the peasant kitchen long after the Sakdalistas were gone, each serving a quiet reminder: revolutions are fed before they are fought.

The ginger and garlic amounts are a floor, not a ceiling. I personally like much more!

Arroz Caldo

Description: A comforting rice porridge with chicken, ginger, and garlic, perfect for cold days.

Ingredients:

- 1 cup glutinous rice (or regular rice)

- 1 lb (500g) chicken thighs, bone-in, cut into pieces

- 8 cups water or chicken broth

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- 4 cloves garlic, minced

- 2-inch piece ginger, julienned

- 2 tbsp fish sauce

- 2 tbsp cooking oil

- 2 boiled eggs, sliced (optional)

- 2 green onions, chopped

- Fried garlic (for garnish)

- Calamansi or lemon wedges

- Salt and pepper to taste

Instructions:

- Sauté: Heat oil in a large pot over medium heat. Sauté garlic, onion, and ginger until fragrant.

- Cook Chicken: Add chicken and cook until lightly browned, about 5 minutes.

- Add Rice: Stir in rice and toast for 1-2 minutes.

- Simmer: Add water or broth and fish sauce. Bring to a boil, then lower heat and simmer for 30-40 minutes, stirring occasionally, until rice is soft and porridge-like. Add more water if too thick.

- Season: Add salt and pepper to taste.

- Serve: Garnish with green onions, fried garlic, boiled eggs, and calamansi wedges. Serve hot.

Notes: For extra flavor, toast the rice longer or use homemade chicken broth.

Sinigang: Sour Truths and Street Fires

Sinigang’s soul is in its sourness, traditionally from sampalok (tamarind) plucked green from the tree, but just as often from calamansi, kamias, green mango, or whatever the season and market stall will yield. Pork, bangus, shrimp, even leftover fish from the morning’s catch; it welcomes all, but hides none. Kangkong wilts in the broth, gabi turns soft and earthy, okra thickens the liquid just enough to cling to the tongue. Every bite reminds you that life, like sinigang, can be bracing and cleansing all at once.

It is one of the oldest dishes in the archipelago’s repertoire, predating the arrival of Spaniards and their galleons. Austronesian ancestors, cooking by riverbanks and in coastal huts, simmered fish with wild sour fruits long before tamarind trees were cultivated in Luzon’s backyards. Over centuries, sinigang adapted, absorbing the pork of colonial livestock, the gabi from trade routes, the tomatoes from Mexico, yet it never lost its defining tang. In that way, it was a culinary map of the Philippines itself: shaped by many hands, yet stubbornly retaining its own flavor.

Sinigang is communal food. It is meant for a pot that sits at the center of the table, surrounded by people dipping ladles into bowls, returning for seconds without asking. It adapts to scarcity as easily as it does to abundance. In the cramped kitchens of student boarding houses or workers’ tenements, the broth could be stretched with more water, the vegetables sliced thin, the pork bones boiled twice to yield every last bit of marrow.

In the late 1960s, that adaptability mirrored the youth movement itself, coalitions of student unions, labor organizers, peasant advocates, church activists, and artists. They came from different provinces, spoke different dialects, and followed different strategies. But in the face of growing inequality and repression, they stewed together into something potent.

And by January 1970, they were boiling over.

Ferdinand Marcos had entered politics in the postwar years with a brilliant smile and an even more brilliant record, at least on paper. He claimed to be a decorated guerrilla hero against the Japanese, a narrative later debunked by U.S. Army investigations but still potent in the young republic hungry for war stories. Charismatic, calculating, and fiercely ambitious, Marcos cultivated the image of a man destined to lead the nation into modernity.

Elected president in 1965, he promised roads, dams, and development. But his first term also brought ballooning foreign debt, swelling military budgets, and cozy deals with political cronies. As his 1969 re-election campaign loomed, Marcos launched a massive public works spree, funded not by surplus, but by unprecedented foreign loans. It was the most expensive campaign in Philippine history, and it bought him victory, but at the cost of a financial crisis. Inflation soared, the peso weakened, and unemployment rose.

The cracks were visible to the youth before most others. They saw how the promises of post-independence democracy had soured into elite musical chairs, with U.S. influence still heavy in Manila’s corridors of power. They watched their parents’ generation, traumatized by war, wary of dissent, remain silent. And they decided to be louder.

On January 26, 1970, Marcos was set to deliver his fifth State of the Nation Address. Outside Congress, thousands gathered: students in worn jeans, farmers’ children clutching placards, laborers carrying banners stitched by their wives. Groups like the Kabataang Makabayan, the Movement for a Democratic Philippines, and countless smaller collectives had converged on the capital.

The protest began in disciplined rows, speeches punctuated by chants. But as Marcos exited the building, flanked by Imelda and an armored security detail, a wooden coffin symbolizing the “death of democracy” was pushed forward. Accounts differ on who threw the first object, but what followed is remembered the same way: batons swinging, shields shoving, tear gas hissing into the crowd. Blood slicked the pavement outside the Batasang Pambansa.

This was the opening act of what became known as the First Quarter Storm; three months of escalating protests, strikes, and street battles. On February 12, thousands marched to the U.S. Embassy, denouncing American imperialism and Marcos’ loyalty to it. Rocks and Molotov cocktails met tear gas and gunfire. Six days later, on February 18, demonstrators surged toward Malacañang Palace itself. The night ended with bodies in the street.

In between these clashes, sinigang simmered. In cramped dorm kitchens, volunteers chopped vegetables and kept the pots warm for those staggering back from the front lines. Workers’ canteens stretched their budgets to ladle pork bone broth into dozens of enamel bowls. The sourness seemed to fit the times; uncompromising, tongue-prickling, a flavor you could not mistake or soften. Between bites, people shared tactics, rumors, poems, and the names of the injured. The pot became a center of gravity; the broth, a kind of truce between exhaustion and resolve.

The First Quarter Storm ended without toppling Marcos, but it shook his palace walls. The youth had tasted their own power, and Marcos had seen their potential to challenge his rule. He labeled them communists, destabilizers, enemies of the state. In private, he prepared the ground for a far more permanent solution.

By 1972, with public unrest still simmering and elections approaching, Marcos declared Martial Law, citing threats of communist insurgency and lawlessness. In truth, it was his bid to hold power beyond the constitutional limit, to rule without opposition. What began in the sour broth of student kitchens would continue underground, in the mountains, and in exile.

The flavor of sinigang lingered through it all, proof that not everything bitter is to be avoided, and that some truths, like some soups, must be tasted in their full strength to awaken you.

In the years that followed, the streets quieted under Martial Law, but the memory of those first months of 1970 remained, like the sour tang of tamarind on the tongue long after the last spoonful. Sinigang’s sharpness was a reminder that the bitterness of resistance could be nourishing, that solidarity could be ladled out even in the leanest of times. The young people who once huddled over steaming bowls in makeshift kitchens would grow older, some forced underground, others scattered abroad, but the taste of that broth, and the truth it carried, would stay with them. And when the moment came to gather again, years later, they would remember not only the chants and the tear gas, but the meals shared in defiance, and the lesson that some flavors, once acquired, never fade.

Southeast Asian soups are superior to all soups. There I said it. This soup does nothing but strengthens that theory.

Sinigang (Tamarind Sour Soup)

Description: A tangy, savory soup with pork (or shrimp) and vegetables, flavored with tamarind.

Ingredients:

- 2 lbs (1 kg) pork ribs or belly, cut into chunks (or 1 lb shrimp)

- 1 pack (40g) tamarind powder (or ½ cup fresh tamarind paste)

- 8 cups water

- Vegetable oil, for searing

- 1 medium onion, quartered

- 6-8 Okra, Halved lengthwise

- 2 medium tomatoes, quartered

- 1 Small knob of Ginger, sliced

- 2-3 Garlic cloves, Smashed

- 1 radish, sliced

- 1 bundle kangkong (or spinach), leaves and tender stems

- 1 eggplant, sliced

- 10-12 pieces green beans, cut into 2-inch lengths

- 1 long green chili (siling pansigang)

- Fish sauce (patis) to taste

- Salt and pepper to taste

Instructions:

- Sear Pork: Heat oil in a large pot on medium. Briefly sear the pork belly until lightly browned.

- Boil Pork: In a large pot, boil pork in water with onion, tomatoes, ginger, and garlic for 45-60 minutes until tender. (For shrimp, skip this step and add shrimp later.)

- Add Tamarind: Stir in tamarind powder (or tamarind paste boiled and strained). Add radish, eggplant, okra, and green beans. Cook for 10 minutes.

- Add Greens: Add kangkong and green chili. If using shrimp, add now. Cook for 3-5 minutes until vegetables are tender and shrimp is pink.

- Season: Add fish sauce, salt, and pepper to taste.

- Serve: Serve hot with rice and extra fish sauce on the side.

Notes: Adjust sourness by adding more tamarind or water. Fresh tamarind or other souring agents (like guava or calamansi) can be used.

Tosilog: Hope on the Morning Plate

Tosilog, a portmanteau of its three core components, tocino, sinangag, and itlog, is a modern classic in Filipino cuisine, but its history is deeply intertwined with the country's culinary traditions and economic landscape.

The heart of the dish is tocino, which literally means "bacon" in Spanish. However, Filipino tocino is a far cry from its Western counterpart. Its origins can be traced back to the Spanish colonial era when methods of preserving meat were introduced. Without modern refrigeration, meat was preserved through curing with salt, sugar, and spices. Over time, Filipinos adapted this process, developing their own unique version that is sweeter and often dyed a distinct red, a color that has become a visual hallmark of the dish. This curing method was a practical way for families to make meat last longer, and it created a beloved flavor profile that became a staple in many households.

The sinangag, or garlic fried rice, has a history rooted in resourcefulness. It's the ultimate example of "no waste" cooking, as it’s traditionally made from day-old, leftover steamed rice. Frying the rice with generous amounts of garlic not only gave it a delicious new life but also ensured that no food was thrown away. This practice reflects the thriftiness and practicality that is a cornerstone of many Filipino kitchen traditions.

Finally, the itlog (egg) completes the trio. The simple addition of a fried egg, typically cooked sunny-side up, was an affordable and quick way to add protein and richness to the meal. Paired with the sweet tocino and savory sinangag, the creamy yolk of the egg provides a perfect balance, binding the different flavors together.

Tosilog, as we know it today, gained widespread popularity in the 20th century as a go-to breakfast for the working class. Its affordability, satisfying flavor, and ability to provide a full day's worth of energy made it the perfect meal for laborers, drivers, and students. It became a symbol of a hearty start to a long day, a meal that was both a comfort and a source of fuel. The concept of combining these three items into a single, cohesive plate led to the creation of the "-silog" category, which now includes many other popular variations like longsilog (with longganisa sausage) and tapsilog (with cured beef tapa).

It’s the kind of meal that fuels jeepney drivers before a shift, dockworkers before first light, students before a long exam, or protesters before they step into history. Affordable, caloric, quick to prepare in a roadside eatery or a kitchen with a single burner, Tosilog has long been the choice of people who know the day ahead will demand everything they have.

In February 1986, the day ahead was nothing less than the dismantling of a dictatorship.

For four days, the world watched as millions of Filipinos filled Epifanio de los Santos Avenue in a vast, unarmed human barricade. They prayed rosaries in unison, sang folk songs, passed bread rolls and thermoses of coffee to strangers, fried eggs on makeshift stoves along the curb. Soldiers sent to disperse them found themselves being handed food instead of fear. This was People Power, peaceful, defiant, miraculous.

And it worked. Ferdinand Marcos, who had ruled under Martial Law for fourteen years, fled to Hawaii. Corazon “Cory” Aquino, widow of assassinated opposition leader Ninoy Aquino, took her oath as president. For a moment, it felt as if the country had been reborn.

But the morning after a revolution is still a morning in a country of the poor.

The landless farmers who had endured Marcos’ broken promises now pinned their hopes on Aquino. Many had marched for her, campaigned for her, prayed for her victory in chapels and rice fields alike. The 1987 Constitution, drafted under her government, enshrined the principle of agrarian reform. But months passed, and the promises remained words on paper.

On January 22, 1987, nearly 10,000 farmers and allies, organized through the Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas, marched to Malacañang to demand land, justice, and action. They had come from provinces far from Manila. Some had eaten only rice and salt on the journey. Others likely began that day with Tosilog. cheap, filling, enough to face the heat and the distance. The aroma of garlic rice may have still clung to them as they reached Mendiola Bridge, chanting for the land that had always been theirs in labor if not in title.

They never reached the palace gates.

Police and military units opened fire. For minutes, chaos reigned, shouting, gunshots, bodies collapsing on the pavement. Thirteen protesters were killed, dozens more wounded. Most were peasants. Some were students. A few were teenagers whose only weapon was a placard.

The Mendiola Massacre did more than kill. It punctured the fragile dream that democracy alone would feed the hungry or return stolen land. Cory Aquino distanced herself from the order to shoot, but trust had been broken, and the farmers returned to their villages not with land deeds, but with coffins.

Still, in the years that followed, the movements persisted. And in the kitchens of those who refused to surrender, Tosilog remained, on tables at dawn before meetings in barangay halls, in canteens where carpenters and market vendors traded news of the struggle, in the homes of families who had lost someone at Mendiola but still rose early, still ate, still fought. It was a breakfast that carried both the sweetness of hope and the salt of disappointment—a plate for people who knew that revolutions, like mornings, always come again, but never guarantee the day you dream of.

It is crucial you use yesterday’s rice and are patient with the pork belly!

Tosilog Recipe: Tocino, Sinangag, and Fried Egg

Yields: 3-4 servings Prep time: 20 minutes (plus at least 4 hours marinating for tocino, ideally overnight) Cook time: 20-30 minutes

I. Filipino Pork Tocino (Sweet Cured Pork)

Ingredients:

- Pork: 1 - 1.5 lbs pork shoulder, pork butt, or pork belly, sliced about 1/4 inch thick

- Sweetness:

- 1/4 - 1/2 cup brown sugar (adjust to your sweetness preference)

- 1/4 - 1/2 cup pineapple juice (helps tenderize the meat and adds tang)

- Savory & Aromatic:

- 2-3 tablespoons soy sauce (low-sodium if preferred)

- 1-2 tablespoons vinegar (cane or white vinegar for balance)

- 4-6 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 teaspoon salt (adjust to taste)

- 1/4 teaspoon black pepper

- Color (Optional, but traditional):

- 1/2 - 1 teaspoon annatto powder (atsuete powder) OR a few drops of red food coloring.

- For Cooking:

- 1-2 tablespoons cooking oil (if needed)

- 1/2 - 1 cup water (for simmering)

Instructions for Tocino:

- Prepare the Pork: Slice the pork against the grain into thin pieces, about 1/4 inch thick.

- Make the Marinade: In a large bowl, combine brown sugar, pineapple juice, soy sauce, vinegar, minced garlic, salt, black pepper, and annatto powder (if using). Mix well.

- Marinate the Pork: Add the pork to the marinade, ensuring all pieces are well coated. Transfer to an airtight container or zip-top bag and refrigerate for at least 4 hours, ideally overnight (8-24 hours).

- Cook the Tocino:

- Place the marinated pork in a frying pan in a single layer. Pour in about 1/2 to 1 cup of water, enough to almost cover the meat.

- Bring to a boil over medium heat, then reduce to low-medium and simmer, uncovered, until the water has almost completely evaporated and the pork is tender.

- Once the water evaporates, add 1-2 tablespoons of cooking oil (if needed). Increase heat slightly to medium.

- Cook, flipping frequently, until the tocino is nicely caramelized, slightly crispy on the edges, and has a sticky, glossy glaze. Watch closely to prevent burning due to the sugar.

II. Sinangag (Filipino Garlic Fried Rice)

Ingredients:

- 3-4 cups day-old cooked white rice (chilled rice is essential to prevent mushiness)

- 4-6 cloves garlic, minced (or more, to taste)

- 2-3 tablespoons cooking oil (vegetable, canola, or the rendered fat from cooking tocino if you have enough)

- 1/2 teaspoon salt, or to taste

- Optional: Pinch of black pepper

Instructions for Sinangag:

- Prepare the Rice: Break up any clumps in the day-old rice with your hands or a spoon.

- Fry the Garlic: Heat the cooking oil in a large wok or frying pan over medium heat. Add the minced garlic. Fry until golden brown and aromatic. Carefully remove about half of the crispy garlic bits and set them aside for garnish. Leave the garlic-infused oil in the pan.

- Fry the Rice: Add the day-old rice to the pan with the garlic-infused oil. Increase the heat to medium-high.

- Season and Toss: Sprinkle the salt (and pepper, if using) over the rice. Stir-fry, breaking up any remaining clumps and ensuring the rice is well coated with the garlic oil. Cook for 5-7 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the rice is heated through and slightly toasted or crispy in spots.

- Combine: Stir in the remaining crispy garlic bits (from step 2) into the rice just before serving.

III. Pritong Itlog (Fried Egg)

Ingredients:

- 3-4 large eggs

- 1-2 tablespoons cooking oil (or use some of the rendered fat from the tocino for extra flavor)

- Pinch of salt and pepper (optional)

Instructions for Fried Egg:

- Heat Oil: Heat the cooking oil in a non-stick frying pan over medium-high heat until shimmering.

- Fry Eggs: Crack each egg directly into the hot pan, being careful not to crowd the pan (fry in batches if necessary).

- Cook to Desired Doneness:

- For sunny-side up (most common for tosilog): Cook until the whites are set and the edges are slightly crispy, but the yolk is still runny. You can spoon hot oil over the whites to help them cook evenly.

- For over easy/medium/hard: Flip the egg after the whites are mostly set and cook to your preference.

- Season: Season lightly with salt and pepper, if desired.

Assembling Your Tosilog Plate:

- On each plate, scoop a generous portion of hot, garlicky sinangag.

- Place a few pieces of the caramelized tocino next to the rice.

- Carefully slide a freshly fried egg on top or alongside the rice and tocino.

- Optional accompaniments:

- A small side of sliced fresh tomatoes for a refreshing counterpoint.

- A small dish of vinegar with a few chili flakes or a dash of soy sauce for dipping the tocino.

- A sprinkle of chopped green onions or more fried garlic on top of the sinangag.

Pancit Canton: Long Noodles for a Long Fight

Pancit Canton's history is a blend of cultural exchange and evolving traditions, deeply rooted in the Philippines' connection with China. The dish is a testament to the long-standing trade and immigration between the two countries.

The name pancit itself is derived from the Hokkien word "pian i sit," which means "convenient food." This reflects its original purpose: a quick and easy-to-prepare meal. Chinese traders and immigrants brought noodles to the Philippines centuries ago, and over time, Filipinos adapted the dish to suit local tastes and available ingredients.

The earliest versions of pancit were likely very simple, focusing on the noodles themselves with minimal additions. As the dish became more integrated into Filipino cuisine, it began to incorporate ingredients native to the islands. The use of local vegetables, meats, and seafood, combined with a distinctly Filipino flavor profile, transformed the Chinese noodle dish into something uniquely Filipino. The addition of calamansi (a small, sour citrus fruit) is a perfect example of this fusion, providing a bright, tangy flavor that is a hallmark of many Filipino dishes.

Nowadays, you can find these noodles everywhere, tossed in hot oil with soy sauce, garlic, and vegetables, then kissed with calamansi for brightness. Tradition says the strands must never be cut, severing them would sever the luck, the life, the prosperity they are meant to carry. In fiestas and birthdays, the dish sits at the center of the table, its unbroken threads linking past to future, family to family.

But in a country where the promise of a “long life” often means a long struggle, pancit canton has also found its place far from the comfort of banquet halls, on strike lines, in protest camps, on tin plates in the shadow of police barricades. The same noodles that once symbolized prosperity became, for many, a symbol of endurance: a meal you can stretch to feed dozens, a food that refuses to break.

By the early 2000s, there was perhaps no place where that symbolism rang truer than Hacienda Luisita. The 6,453-hectare sugar plantation in Tarlac province was owned by the Cojuangcos, one of the most powerful political families in the Philippines, and kin to former president Corazon Aquino.

The estate’s history was rooted in a broken promise. In the late 1950s, the Cojuangcos had purchased the land with government financing under the agreement that it would be redistributed to the farmers who worked it. Decades passed. No redistribution came. The fields remained a fiefdom of sugarcane monoculture, where the harvest flowed upward in wealth, and the farmers who planted, cut, and hauled remained landless.

When Cory Aquino rose to the presidency after the People Power Revolution, hopes for reform surged. The Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) of 1988 seemed to offer a path toward justice. But Hacienda Luisita was exempted through a legal sleight of hand called the Stock Distribution Option. Farmers would receive shares in the corporation instead of actual parcels of land, shares that brought no real control, no power to decide what was planted, harvested, or earned.

By 2004, years of stagnant wages, mass layoffs, and empty promises boiled over. On November 6, more than 5,000 sugar workers and farm laborers walked off the fields and blockaded Hacienda Luisita’s Gate 1. Their demands were direct: just wages, reinstatement of the dismissed, and land that had been pledged to them generations earlier.

The picket line became a community. Union leaders gave speeches over crackling megaphones. Farmers’ children played tag in the dust. Cooking fires burned from dawn to dusk. Pancit canton was ladled from foil trays, the noodles tangled with scraps of pork and cabbage, feeding dozens at a time. Volunteers poured lukewarm coffee into tin cups, fried eggs beside mounds of garlic rice, passed bread rolls down the line. Food was never just food—it was proof that they could sustain each other in the fight.

On November 16, the police and military moved in. Tear gas canisters arced over the barricades. Trucks smashed through lines of shouting farmers. Then the gunfire began.

When it was over, seven lay dead. Dozens were wounded. Hundreds were dragged away in handcuffs. The Luisita Massacre sent shockwaves across the country, not because the victims were armed rebels, but because they were workers, unarmed and in plain sight, killed for demanding what had been theirs in principle for nearly half a century.

The fight did not die with them. For eight more years, survivors and their allies carried the case through courts, congressional hearings, and public campaigns. Some witnesses were harassed or disappeared. Many families sank deeper into poverty. But in 2012, the Supreme Court ordered that the land be distributed to the farmers at last. It was a rare legal victory, but it came too late for the seven dead, and too late for many who had grown old waiting for justice.

Still, the strike at Hacienda Luisita cracked the illusion that elite power could not be challenged. It proved that even the most fortified estates could be breached; not by force of arms, but by the collective will of those who refused to break.

And so, in the makeshift kitchens that had sprung up along the picket line, the pans of pancit canton kept sizzling. Long noodles for a long war, because some fights, like the strands, were never meant to be cut short.

If you have no calamnsi, lemons work!

Pancit Canton

Description: Stir-fried egg noodles with vegetables, meat, and a savory sauce.

Ingredients:

- 1 lb (450g) canton noodles (egg noodles)

- ½ lb chicken breast, sliced thinly

- ½ lb shrimp, peeled and deveined

- 1 cup pork, sliced thinly (optional)

- 1 medium carrot, julienned

- 1 cup cabbage, shredded

- 1 cup green beans, sliced diagonally

- 1 bell pepper, sliced

- 1 medium onion, sliced

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- ¼ cup soy sauce

- 2 tbsp oyster sauce

- 2 cups chicken broth

- 2 tbsp cooking oil

- Salt and pepper to taste

- Calamansi or lemon wedges

Instructions:

- Sauté: Heat oil in a large wok over medium-high heat. Sauté garlic and onion until fragrant.

- Cook Meat: Add chicken and pork (if using). Cook until lightly browned. Add shrimp and cook until pink, about 2 minutes. Remove shrimp and set aside.

- Cook Vegetables: Add carrots, green beans, and bell pepper. Stir-fry for 3-4 minutes. Add cabbage and cook for 1 minute.

- Add Noodles: Pour in soy sauce, oyster sauce, and broth. Add noodles and stir-fry until noodles are soft and have absorbed the sauce, about 5-7 minutes.

- Combine: Return shrimp to the wok. Season with salt and pepper.

- Serve: Serve hot with calamansi wedges.

Notes: Adjust broth to prevent noodles from drying out. Add more vegetables like snow peas or celery for variety.

Comments

Post a Comment