Nigeria: Fufu and Fire

Nigeria: Fufu and Fire

Nigeria has always been more than the sum of its parts. Before the British ever set foot on its shores, the land was a vibrant tapestry of kingdoms, empires, and city-states, from the powerful Yoruba kingdoms in the southwest to the ancient Kanem-Bornu Empire in the northeast, and the decentralized Igbo communities in the southeast. This was not a blank slate, but a dynamic, complex region with established trade routes, political systems, and a rich history of art and innovation.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 changed everything. With a few strokes of a pen, European powers carved up Africa, ignoring centuries of history and culture. Nigeria, a name invented by a British journalist, was born out of this arbitrary division. The British, driven by the era's ruthless imperialism, set out to consolidate their control. Their system of indirect rule was a masterclass in exploitation and manipulation. They co-opted or installed traditional rulers, granting them authority in exchange for enforcing colonial policies: collecting taxes, conscripting labor, and ensuring a steady flow of raw materials back to Britain. This strategy exacerbated pre-existing ethnic and religious differences, pitting groups against each other and laying the groundwork for future conflicts. The North, primarily Hausa-Fulani and predominantly Muslim, was governed differently from the South, which was home to the predominantly Christian Yoruba and Igbo, creating a political divide that would haunt the nation for decades.

This colonial order was never accepted quietly. The people of Nigeria, from coast to desert, fought back. The 1929 Aba Women's War saw tens of thousands of Igbo women take to the streets, not just against new taxes, but against the loss of their political voice and the indignity of colonial rule. This was followed by the 1945 General Strike, a landmark moment where workers, inspired by rising anti-colonial sentiment, brought the entire country to a standstill. Rail workers, teachers, and civil servants demanded fair wages and better working conditions, demonstrating a unified defiance that the British could not ignore. This strike was a crucial turning point, signaling that the end of colonial control was no longer a question of "if," but "when."

Independence in 1960 was meant to be the dawn of a new era. But the fragile nation-state inherited the British-designed political system, one that favored regional strongmen and amplified ethnic tensions. The first republic quickly descended into chaos, culminating in a series of military coups that would dominate Nigerian politics for the next three decades. The discovery of oil in the Niger Delta should have been a blessing, but it became a curse. Foreign oil companies, in league with corrupt military juntas and civilian governments, extracted billions in wealth, leaving the environment devastated and the local population impoverished. This created a new kind of tyranny, one where the country's riches flowed upward to a small, privileged elite while ordinary Nigerians were left to suffer the effects of austerity, economic mismanagement, and brutal repression.

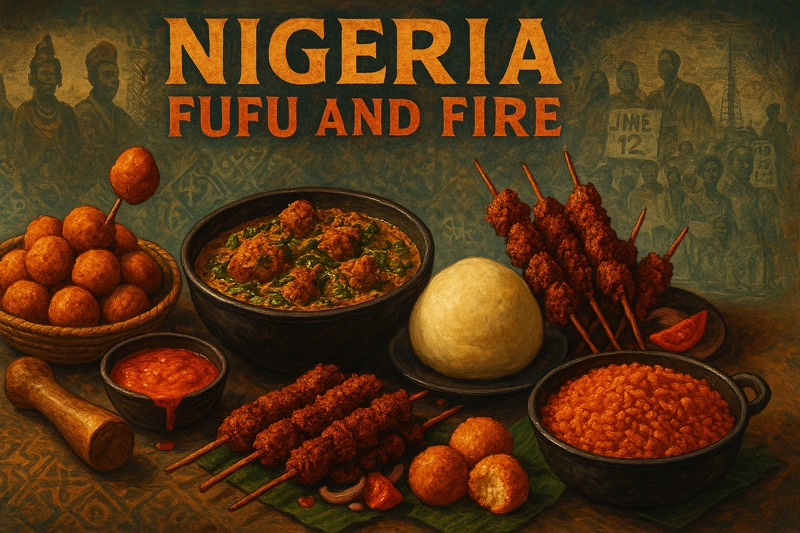

Through it all, food remained an anchor. Nigerian cuisine is a testament to this history, a rich, flavorful fusion of ingredients and techniques shaped by necessity, migration, and trade. Much like Fela Kuti's Afrobeat, which blended traditional Yoruba music with jazz and funk to create a potent soundtrack of protest, Nigerian food is a defiant art form. It is the communal act of sharing a meal, the simple sustenance that fuels resistance, and the powerful symbol of a culture that refuses to be erased.

This is the story of five dishes; five moments when the kitchen became a battleground, and the pot boiled over into protest. We begin with Fufu and Egusi, the nourishing fuel for the 1945 General Strike. We then turn to Akara, a symbol of the 1947 Abeokuta Women's Revolt. Next is Suya, the rallying cry of the 1989 Anti-SAP Riots. We center on Jollof Rice during the 1993 June 12 protests, and finally, we taste Puff-Puff, the sweet and subversive treat of the 2012 Occupy Nigeria movement. These are not just recipes; they are the edible archives of a people's struggle, a defiant legacy served with heat, memory, and a side of resistance.

So light the charcoal stove, pound the yam, and stir the pot, these dishes are best served with heat, memory, and a side of resistance.

Fufu and Egusi: Feeding the Strike

Fufu is ubiquitous throughout West Africa. Originally made from mashed cocoyam, plantains, or yams, these starchy balls have been used as a side for food for centuries. Portuguese traders introduced cassava root from Brazil in the 16th century, and it became a popular ingredient for fufu, due to its ease of cultivation. Egusi soup, made from ground melon seeds, greens, red palm oil, and various meats, has been cultivated and eaten for 5,000 years in the area now known as Nigeria. Fufu is often used as a sort of "spoon" to help both soak up the stew and eat it. It was never a meal for the wealthy. Farmers, laborers, teachers, the people who powered the colonial economy, that's who this dish was for, and in 1945, they took it to the streets in protest.

Under British colonial rule, Nigeria's workers were supposed to know their place. The colonial economy ran on their backs, while the profits flowed to London, a simple economic pipeline extracting resources from West Africa to the UK. Civil servants were overworked and underpaid. Railway workers lived in cramped quarters. Market women were taxed and harassed. Inflation after World War II sent the price of goods soaring, but wages stayed flat. Fufu and Egusi, once everyday fare, started to feel like a luxury. Workers couldn't afford meat. Palm oil grew scarce. Yam prices spiked. Still, every evening, in homes from Lagos to Kano, people gathered around bowls of it, stretching each scoop, savoring what little remained. It was a quiet refusal to be broken; edible endurance.

But they wouldn't stay quiet for long.

By June of 1945, discontent had reached a breaking point. A spark was lit in Lagos, where railway workers, postal clerks, and artisans began to whisper of a general strike. They were joined by teachers, factory workers, nurses, and students; Black Nigerians who made the system run, but were excluded from its benefits. On June 22, they walked out. Over 200,000 workers across the country downed tools. The ports were closed. Trains sat idle. Government offices were shuttered. Streets once humming with labor fell silent. The illusion of colonial control was shattered.

At strike camps and community kitchens during the 44-day strike, food became a tool of resistance. With money tight, organizers pooled what they had. Women, often the backbone of the household in colonial Nigeria, cooked vats of egusi soup in aluminum pots over charcoal fires. Fufu was pounded communally, fist after fist slamming into mortars, the thud of each strike echoing their cause. Vendors handed out bowls to strikers. Neighbors brought ingredients. The meal didn't just nourish, it unified. The daily food distribution helped strengthen the strikers' resolve.

The British colonial government panicked. They attempted to shame and coerce the strikers back to work, calling them "ungrateful" and "disloyal" in the press. But the workers held the line. For 44 days, the country stood still. And then, the government gave in, facing complete economic paralysis. Wages were increased and conditions were slightly improved, but the strike had far more than just an economic impact. More importantly, the myth of colonial omnipotence cracked, and Nigerians saw they could fight the might of the British Empire and win. It was the first nationwide general strike in Nigerian history, and it had been fed, quite literally, by the same meal that fed the nation's soul.

As the strike ended and workers returned to their posts, Fufu and Egusi returned to dinner tables in its familiar form: now not just a meal, but a memory of the people's resounding victory.

This spirit of rebellion would re-emerge just two years later, not in the form of a nationwide strike, but in the streets of Abeokuta.

I cannot describe Fufu and Egusi as like anything I have had before. If you like spice, it is delicious.

Fufu

Fufu is a starchy, dough-like staple often served with soups like Egusi. It's commonly made from cassava, yam, or plantain.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups cassava flour (or yam flour, or a mix of cassava and plantain flour)

- 4 cups water

Instructions:

- Boil water: Bring 4 cups of water to a boil in a large pot.

- Make paste: In a bowl, mix 1 cup of cassava flour with 1 cup of cold water to form a smooth paste.

- Cook mixture: Gradually pour the paste into the boiling water, stirring constantly to prevent lumps.

- Thicken: Reduce heat to medium. Add the remaining 1 cup of flour gradually, stirring vigorously until the mixture thickens into a smooth, elastic dough (about 10-15 minutes).

- Shape: Remove from heat. Wet your hands, scoop portions, and roll into balls or shape as desired.

- Serve: Serve warm with Egusi soup or any preferred stew.

Tips: Adjust water for desired softness. Fufu is typically eaten by pinching off small pieces and dipping them into soup.

Egusi (Melon Seed Stew)

Egusi is a rich, savory stew made from ground melon seeds, often cooked with vegetables and protein.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups ground egusi (melon) seeds

- 1 lb beef, chicken, or fish (cut into chunks)

- 1 cup palm oil

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- 2 cups spinach or ugu (fluted pumpkin) leaves, chopped

- 2 tablespoons ground crayfish

- 2-3 Scotch bonnet peppers, blended (adjust for spice)

- 2 cups stock (chicken, beef, or vegetable)

- 1 tablespoon locust beans (optional, for authentic flavor)

- Salt and seasoning cubes (e.g., Maggi) to taste

Instructions:

- Cook protein: Season meat or fish with salt and a seasoning cube. Boil in 2 cups of stock until tender (about 20-30 minutes). Set aside, reserving the stock.

- Prepare egusi paste: Mix ground egusi with a little water to form a thick paste.

- Sauté base: Heat palm oil in a large pot over medium heat. Add chopped onions and sauté until translucent (about 3 minutes).

- Cook egusi: Add the egusi paste to the pot, stirring frequently for 5-7 minutes until it starts to clump and release a nutty aroma.

- Add stock and seasonings: Pour in the reserved stock, ground crayfish, blended peppers, and locust beans (if using). Stir and simmer for 10 minutes.

- Add protein and vegetables: Add cooked meat or fish and chopped spinach/ugu. Simmer for another 5-7 minutes until the stew thickens and the vegetables are tender.

- Adjust seasoning: Taste and adjust with salt and seasoning cubes. If too thick, add a little water.

- Serve: Serve hot with fufu, pounded yam, or rice.

Tips: For a smoother texture, blend egusi with onions before cooking. Adjust palm oil for richness.

Akara: Bean Cakes and Broken Crowns

Made from peeled and ground black-eyed peas, whisked with onion and chili into a fluffy batter, and then spooned into bubbling oil until golden and crisp, akara is street food in its purest form: portable, nourishing, and democratic. It was a pre-colonial staple of the culture of the Yoruba people, prepared for events like the funerals of elders and to welcome victorious warriors. This continued even into the era of British colonial rule. Sold on corners before dawn and at bus stops well into the evening, it is most often sold by women: mothers with headscarves tied tight, balancing trays on their heads and children on their hips, feeding a nation one sizzling scoop at a time. And in the city of Abeokuta, in 1947, the very women who fried akara in the early morning smoke decided they'd had enough.

The trouble had been simmering for years. Under British colonial rule, Nigeria's taxation system was a machine designed to extract, and women were the gears greased with hardship. The colonial administration ruled indirectly, through local male leaders known as Obas. In Abeokuta, the most powerful of them was the Alake of Egbaland, a man who claimed authority not only from British endorsement but from traditional structures now twisted in the service of empire. The Alake, with British backing, imposed direct taxes on women, particularly market traders, many of whom earned just enough to scrape by. These weren't symbolic levies. They were enforced through harassment, fines, and raids by colonial tax agents.

At the heart of this injustice were the women who sold food: fishmongers, pepper sellers, palm oil vendors, and akara fryers. They were taxed for simply existing in the economy they sustained. And they were not represented in the councils that taxed them.

That changed when a former teacher, activist, and suffragist named Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti stepped into the ring. Alongside a group of fierce, organized, working-class women, she founded the Abeokuta Women's Union (AWU). The AWU was no elite tea-circle. It was a militant, mass movement of over 20,000 women, many of them market traders and street vendors, who decided to challenge both the colonial state and the traditional patriarchy propping it up.

Meetings were held in courtyards and backrooms, where akara sizzled in nearby pans as women passed news, planned actions, and stirred resistance alongside their batter. Akara became sustenance for meetings that stretched past sunset, food for young children brought along in the arms of their activist mothers, and small income to fund a struggle that was growing in boldness. Akara, simple as it was, helped keep the fight fed.

And then the fight took to the streets.

The women of Abeokuta launched a campaign of mass protest in October 1947, marching in the thousands to the Alake's palace. They sang protest songs, some of them satirical chants comparing the Alake to a greedy glutton. They laid siege to government offices, blocking roads, and occupying public space with their bodies. They refused to pay the tax. They wrote petitions. When ignored, they returned in force. Over months, they endured harassment, arrests, and brutal policing, but they kept coming.

Eventually, the Alake cracked. In 1949, he abdicated his throne, a seismic event that shook the colonial structure to its core. The colonial taxation system on women was dismantled in Abeokuta. And the AWU helped inspire broader women's movements across Nigeria, laying the groundwork for national resistance, feminism, and democracy in the decades ahead.

And still, every morning, akara sizzled in hot oil, just as it had before. But now, it carried something extra: the memory of when the women who cooked it helped dethrone a king.

If you are able to work up the patience to unpeel every bean, these fritters are a miracle on a plate.

Akara (Bean Fritters)

Akara is a savory fritter made from blended black-eyed peas, often served as a snack or breakfast item.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups dried black-eyed peas (soaked overnight)

- 1 small onion, finely chopped

- 1-2 Scotch bonnet peppers, finely chopped (adjust for spice)

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon ground crayfish (optional)

- Vegetable oil for deep frying

Instructions:

- Prep beans: Drain soaked black-eyed peas. Rub beans between your hands to remove skins, then rinse until most skins are gone.

- Blend: Blend peeled beans with 1/4 cup water until a smooth, thick paste forms. Add a little more water if needed, but keep it thick.

- Mix batter: Transfer paste to a bowl. Add onions, peppers, salt, and crayfish (if using). Whisk vigorously for 2-3 minutes to incorporate air for fluffiness.

- Heat oil: Heat 2-3 inches of oil in a deep pot to 350°F.

- Fry akara: Scoop tablespoon-sized portions of batter and drop into hot oil. Fry in batches for 3-4 minutes per side until golden and crispy.

- Drain: Remove with a slotted spoon and drain on paper towels.

- Serve: Serve hot with a side of pepper sauce or as a side to Jollof Rice.

Tips: Soaking beans overnight makes peeling easier. Blend in small batches for a smoother paste.

Akara Pepper Sauce

Ingredients:

- 2-3 fresh habanero peppers (or 1-2 Scotch bonnet peppers, if available), stemmed and roughly chopped

- 1/2 tsp Scotch bonnet powder (adjust to taste for extra heat)

- 1 small red bell pepper, seeded and chopped (for sweetness and body)

- 1 small onion, roughly chopped

- 2 cloves garlic

- 1 medium tomato, chopped (or 2 tbsp tomato paste for a richer flavor)

- 1/4 cup vegetable oil

- 1 tsp ground crayfish (optional, for umami, common in West African cuisine)

- 1/2 tsp salt (adjust to taste)

- 1/4 tsp sugar (optional, to balance acidity)

- 1/4 cup water or vegetable broth (to adjust consistency)

- 1 tbsp lemon juice or white vinegar (for tanginess)

Instructions:

- Blend ingredients: In a blender or food processor, combine habanero peppers, red bell pepper, onion, garlic, and tomato (or tomato paste). Blend until smooth, adding a splash of water if needed to help it blend.

- Cook the sauce: Heat the vegetable oil in a small saucepan over medium heat. Pour in the blended mixture and stir in the Scotch bonnet powder, ground crayfish (if using), salt, and sugar. Cook for 10-12 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the sauce thickens and the raw taste of the vegetables cooks out. The oil may separate slightly, which is normal.

- Adjust consistency: Add water or broth gradually to reach your desired thickness (should be slightly thick but pourable, like a dipping sauce).

- Add tanginess: Stir in the lemon juice or vinegar. Taste and adjust seasoning, adding more salt, sugar, or Scotch bonnet powder if needed.

- Cool and serve: Remove from heat and let cool slightly. Serve warm or at room temperature alongside hot Akara for dipping or drizzling.

Suya: Smoke and Sparks

Suya isn't just food. It's a social ritual. The clatter of metal skewers and the hiss of meat on charcoal are a soundtrack to Nigeria's crowded cities. A specialty of the nomadic Northern Hausa people that migrated south, Suya is spicy grilled beef or chicken, sliced thin and coated in a dry rub of ground peanuts, chili, ginger, and spices. It's cooked in the open, served in newspaper or foil, and eaten with onions, tomatoes, and a fiery pepper mix that makes your lips burn and your eyes water. It's dinner on the go, food for the night shift, the student, the taxi driver, the rebel.

By the late 1980s, that rebel had good reason to rise.

Nigeria, a nation rich in oil reserves, had been mismanaged by a series of corrupt military governments since the 1970s. These regimes borrowed heavily against future oil revenues, funding grandiose projects and lining their own pockets while the country spiraled into debt. When global oil prices collapsed in the 1980s, Nigeria's economy imploded. Faced with a looming financial crisis, the military government turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout. The IMF, being slightly more forgiving than a mafia loan shark, demanded the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) as the price of aid.

This SAP was to be a neoliberal dream: cut government spending, float the currency, eliminate subsidies, and privatize state enterprises. On paper, it was economic reform. In practice, it was austerity with a foreign accent. Food prices skyrocketed, including the price of eggs and rice. The cost of transportation soared due to the removal of fuel subsidies. Jobs vanished. Universities crumbled. Hospitals ran out of supplies. The rich hedged with foreign currency and connections. The poor were left to fend for themselves with little but hope, and Suya.

In the chaos of Lagos nights, Suya became more than street food. It was the poor man's steak, a delicacy compressed into slivers. When eggs were too expensive and imported rice doubled in price, Suya was still there, sold in alleys and roadside stalls lit by kerosene lamps. It was affordable, filling, and shared among friends over heated talk of rent, fuel lines, and betrayal. People joked that the only thing not "adjusted" was Suya's heat level, it still burned your throat like a match.

But by May 1989, the jokes stopped.

The SAP policies had triggered widespread anger. That May, the Nigerian Labour Congress called a national strike to protest the regime's decision to hike fuel prices, a move that hit transport costs, food distribution, and daily life. Workers walked off their jobs. Students occupied campuses. Demonstrators flooded the streets in cities from Lagos to Ibadan to Kano. The largest protests since independence gripped the nation.

In Lagos, the air stung with tear gas, and the scent of Suya. Vendors kept grilling into the evenings, feeding protesters who took quick bites before ducking police batons. Activists huddled in corners of the University of Lagos, trading news and roasted meat. Strikers passed around Suya wrapped in newspaper, its peppery bite matching the anger in their voices. It was fuel for the movement, fire for the belly and the soul.

The government responded with force. Security forces shot into crowds. Dozens were killed. Hundreds arrested. The protests were violently crushed, but the message was clear: the people were done being silent. For the first time since the Civil War, a multi-class, multi-ethnic uprising had erupted, not against a tribe or a religion, but against economic strangulation itself.

Suya, meanwhile, endured. Vendors cleaned their grills and returned to their corners. The scent of spice and charcoal drifted back into the streets. But the smoke now carried memory.

Don't forget to toast the peanuts! And prepare for your eyes to water!

Suya

Ingredients (Serves 4):

- Beef: 1 lb (450g) sirloin or top round, thinly sliced

- Suya spice mix:

- 1/2 cup roasted peanuts (or peanut powder)

- 1 tbsp ground ginger

- 1 tbsp smoked paprika

- 1 tbsp cayenne pepper (adjust for heat preference)

- 1 tbsp onion powder

- 1 tsp garlic powder

- 1 tsp ground black pepper

- 1 tsp salt

- 1 tsp ground chili powder (optional, for extra heat)

- Vegetable oil: 2 tbsp (for brushing)

- Skewers: Wooden or metal

- Optional garnish: Sliced onions, tomatoes, and cucumber

Instructions:

- Prepare the suya spice: If using whole peanuts, pulse them in a food processor to a fine powder (avoid overprocessing into peanut butter). Mix the peanut powder with ginger, paprika, cayenne, onion powder, garlic powder, black pepper, salt, and chili powder in a bowl. Set aside.

- Prepare the meat: Slice beef into thin strips (about 1/4 inch thick) for easy grilling. Thread the beef strips onto skewers, weaving them accordion-style.

- Marinate: Brush the meat lightly with vegetable oil to help the spice stick. Generously coat the skewered meat with the suya spice mix, pressing it into the meat. Reserve some spice for serving. Let the meat marinate for 30 minutes at room temperature (or up to 4 hours in the fridge for deeper flavor).

- Grill: Preheat a grill (or oven broiler) to medium-high heat (about 400°F/200°C). Grill the skewers for 8-10 minutes, turning occasionally, until the meat is cooked through and slightly charred at the edges. (For oven, broil on a baking sheet for 6-8 minutes, flipping halfway.)

- Serve: Remove skewers from the grill and sprinkle with extra suya spice if desired. Serve hot with sliced onions, tomatoes, and cucumber on the side for a traditional touch.

Jollof Rice: A Feast Interrupted

Jollof Rice is a dish of celebration, but its origins are rooted in survival. West African at its heart, the dish traces back to the 14th-century Wolof Empire (now parts of Senegal and The Gambia), where rice cultivation and trade flourished along the Niger and Senegal rivers. Over centuries, the dish evolved, spreading across West Africa through migration, empire, and colonization. Each country adapted it, but the Nigerian version, with long-grain parboiled rice, tomatoes, scotch bonnets, onions, and sometimes meat or fish, stands apart for its fiery flavor and cultural symbolism.

In Nigeria, Jollof is not just food. It is the centerpiece of birthdays, weddings, and naming ceremonies. It's cooked in massive aluminum pots over open flames at roadside parties, stirred with wooden paddles, and scooped onto plastic plates at community halls. It's eaten in homes, churches, and schools. It belongs to everyone: Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, and beyond. And in the summer of 1993, when democracy itself was on the line, Jollof Rice was there, feeding a movement.

The years leading up to 1993 were a dark chapter in Nigerian history. Following a succession of military coups, the country had been under the brutal and corrupt rule of military dictatorships, first under General Muhammadu Buhari and then General Ibrahim Babangida. These regimes stifled dissent, jailed journalists, and oversaw an economic collapse fueled by mismanagement and the devastating Structural Adjustment Program (SAP). By 1993, the Nigerian people were desperate for a return to civilian rule and democracy. A presidential election was finally scheduled for June 12, and the country held its breath. The economy was in crisis, the streets tense, and hope a scarce commodity. But that day, sunny, crowded, and electric, offered something else: unity.

The man leading the vote was Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola, a wealthy Yoruba businessman and philanthropist who had built goodwill across regions through media, scholarships, and charity. He campaigned not as a southern candidate, but as a pan-Nigerian figure. His party, the Social Democratic Party (SDP), ran on promises of economic revival, civil liberties, and civilian governance. And when early results showed Abiola winning by a landslide, garnering votes in both the Muslim North and Christian South, it felt like the country was finally healing.

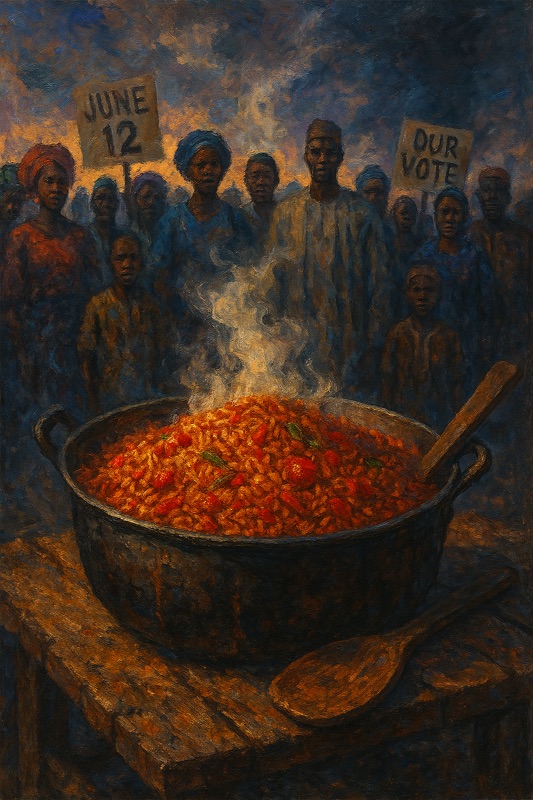

People celebrated in the streets. Radio stations played jubilant music. Vendors hawked meat pies and sachets of water. And from Lagos to Kaduna, the smell of Jollof Rice filled the air. It was served in homes as families gathered to watch the results trickle in. It was scooped into bowls for election volunteers. It was cooked by hopeful hands that believed the next day would be the beginning of a new Nigeria.

But that tomorrow never came.

On June 23, just eleven days after the vote, the military government, led by General Ibrahim Babangida, annulled the election. No official winner. No explanation. The press was muzzled. Protests erupted immediately. People were shocked, then furious. That fury turned into fire.

In the weeks that followed, Nigeria exploded with mass protests and civil disobedience. Lagos, Ibadan, Kano, and Port Harcourt became battlegrounds of resistance. Students marched. Labor unions called strikes. Activists, journalists, and clergy stood shoulder to shoulder. And as rubber bullets flew and tear gas clouded the streets, Jollof Rice still simmered, in protest camps, kitchens, and roadside stalls.

Women cooked it for exhausted demonstrators. Teachers shared pots of it with students before heading out to rally. In middle-class homes where politics had once been taboo, families stirred tomato paste and Maggi cubes into rice and talked openly of betrayal and revolution. Jollof Rice, once the food of unity, now became the food of defiance.

The government's crackdown was brutal. Moshood Abiola was arrested and detained, and dozens of protestors were killed. But the spirit of June 12 could not be extinguished. It became a powerful rallying cry for democracy, a symbol of a moment when Nigerians, across all ethnic and religious lines, had united for a common cause. While the military regime remained in power for several more years, the legacy of June 12 was a constant reminder of the people's will. When Nigeria finally returned to civilian rule in 1999, the day was not forgotten. In 2018, June 12 was officially declared Democracy Day, a tribute not to the day power was transferred, but to the day Nigerians truly claimed it for themselves. The feast had been interrupted, but the struggle for democracy had just begun.

Jollof Rice is one of the top three rice dishes I've eaten. I hope you think the same.

Jollof Rice

Jollof Rice is a vibrant, one-pot rice dish cooked in a tomato-based sauce, popular across West Africa.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups long-grain parboiled rice

- 1/4 cup vegetable oil

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- 1 red bell pepper, blended

- 3 medium tomatoes, blended (or 1 cup canned tomato puree)

- 2 tablespoons tomato paste

- 2-3 Scotch bonnet peppers, blended (adjust for spice)

- 1 teaspoon thyme

- 1 teaspoon curry powder

- 2 bay leaves

- 2 cups chicken or vegetable stock

- 1 cup water

- 1 lb chicken (optional, cooked and fried)

- Salt and seasoning cubes to taste

Instructions:

- Prep rice: Rinse rice thoroughly until water runs clear. Parboil for 5-7 minutes, drain, and set aside.

- Make sauce base: Heat oil in a large pot over medium heat. Sauté onions until translucent (about 3 minutes).

- Cook tomato base: Add blended tomatoes, red bell pepper, Scotch bonnet peppers, and tomato paste. Cook for 5-7 minutes until thickened.

- Season: Add thyme, curry powder, bay leaves, salt, and seasoning cubes. Stir well.

- Cook rice: Add parboiled rice, stock, and water. Stir, bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low. Cover and simmer for 20-25 minutes until rice is cooked and liquid is absorbed.

- Add protein (optional): If using chicken, nestle fried chicken pieces into the rice during the last 5 minutes.

- Serve: Fluff rice with a fork, remove bay leaves, and serve hot.

Tips: For smoky flavor, grill the bell peppers before blending. Adjust stock for desired moisture level.

Puff-Puff: Fried, Filled, and Fed Up

Puff-Puff is Nigeria's favorite sweet snack: bite-sized balls of deep-fried yeast dough, golden on the outside, fluffy on the inside. It's affordable, quick to make, and found just about everywhere: market stalls, school courtyards, roadside vendors, and church gatherings. Every region, every income level, every child and elder has had their hands coated in sugar or their mouths full of hot puff-puff. Its joy is in its simplicity: flour, sugar, yeast, water, a bit of salt, maybe nutmeg if you're feeling fancy. Yet it speaks volumes. It's a treat for the working class, sweet and accessible, the food of everyday people.

And in January 2012, everyday people had had enough.

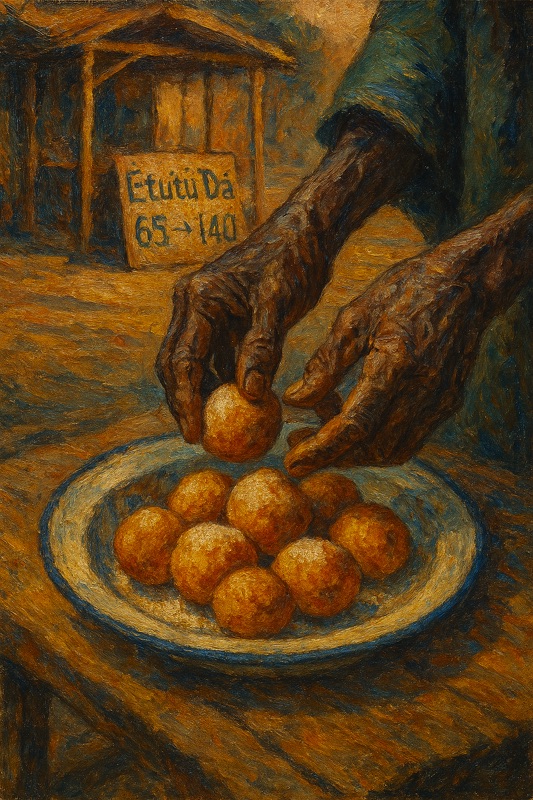

It started, as it often does, with a price hike. On New Year's Day, the Nigerian government under President Goodluck Jonathan announced the removal of fuel subsidies, a policy that had, for decades, kept petrol artificially affordable for the masses. Fuel prices more than doubled overnight, jumping from 65 naira to over 140 naira per liter. In a country where public transportation, small businesses, electricity (via generators), and even food prices are tied to the cost of petrol, this wasn't a minor inconvenience. It was a crisis.

Suddenly, everything was more expensive, except wages.

For the poor and working class, this felt like betrayal. Many didn't own cars, but they relied on buses, bikes, and shared vans to get to work, to school, to the market. Food sellers who made puff-puff at dawn now had to pay double for the kerosene or diesel they used to heat their oil. And worse, they had to raise their prices, knowing that their customers; drivers, cleaners, teachers, and students, could barely afford the old ones. Some stopped frying altogether. Some kept frying and sold for credit. And others gave puff-puff away, not because they could afford to, but because they couldn't bear to turn away a hungry child.

In that struggle, something ignited.

What began as frustration soon erupted into a national movement: Occupy Nigeria.

The name echoed global protests like Occupy Wall Street, but this was uniquely Nigerian. It was driven not just by youth and civil society, but by unions, religious leaders, students, market women, musicians, and artisans. On January 9, a general strike began. The streets of Lagos, Kano, Ibadan, Abuja, and Port Harcourt flooded with people. Protesters shut down highways. Offices were closed. Markets empty. Churches and mosques opened their doors to demonstrators. Musicians set up speakers. Vendors handed out free puff-puff and water sachets to keep morale up.

In the chaos, puff-puff became a symbol. It was fried in protest camps, served beside placards, passed around by uncles and aunties standing firm in sandals and sunglasses. Some called it "resistance food." It reminded everyone why they were there: not for political elites or abstract economics, but for the basic dignity of being able to afford breakfast. The smell of oil and sugar drifted through the crowds like incense, a small comfort against riot police and government indifference.

As pressure mounted, so did the state's response. Police were deployed. Curfews were declared. Tear gas was fired. Protesters were killed. But the crowds didn't leave. They stayed. Danced. Sang. Fried more puff-puff.

Faced with the unrelenting pushback, the government eventually conceded. On January 16, President Jonathan announced a partial reinstatement of fuel subsidies, bringing prices down, though not all the way. The protests ended, but the message had been sent. Nigerians had drawn a line in the sand: decisions made without the people would be answered by the people.

Occupy Nigeria didn't lead to a revolution, but it reset expectations. It reminded leaders that the poor are watching, organizing, and rising. And it reminded the people that their power lies not just in protest, but in collective daily action, in choosing to care, to resist, even if only by sharing a piece of fried dough.

Puff-Puff

Puff-Puff is a sweet, deep-fried dough ball, a popular snack or dessert.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 2 teaspoons instant yeast

- 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg (optional)

- 1 cup warm water (100-110°F)

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract (optional)

- Pinch of salt

- Vegetable oil for deep frying

Instructions:

- Make dough: In a large bowl, mix flour, sugar, yeast, nutmeg, and salt. Gradually add warm water and vanilla, stirring until a smooth, thick batter forms.

- Rest dough: Cover and let the batter rest in a warm place for 1-1.5 hours until doubled in size.

- Heat oil: Heat 2-3 inches of oil in a deep pot to 350°F.

- Fry puff-puff: Scoop tablespoon-sized portions of batter using a spoon or your hands (wet hands to prevent sticking). Drop into hot oil, frying in batches to avoid crowding. Fry for 2-3 minutes per side until golden brown.

- Drain: Remove with a slotted spoon and drain on paper towels.

- Serve: Dust with powdered sugar (optional) and serve warm.

Tips: Ensure oil is hot enough to prevent greasy puff-puff. Use a thermometer for best results.

Comments

Post a Comment