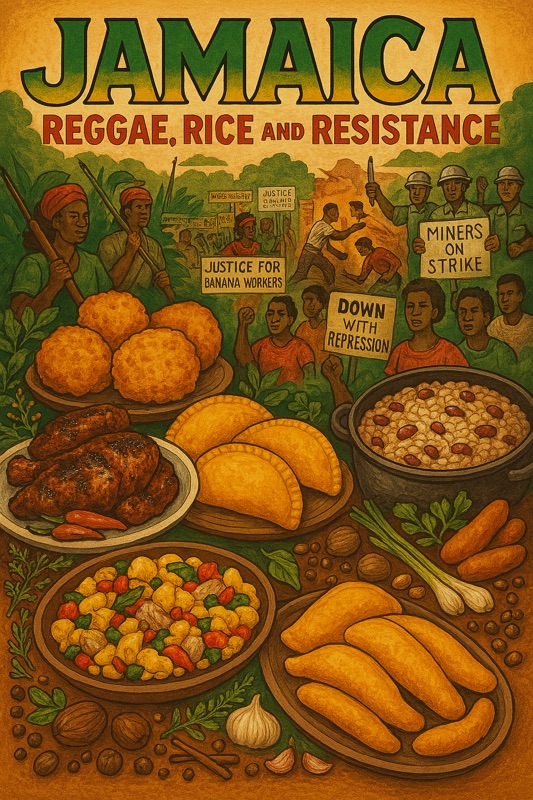

Jamaica: Rice, Reggae, and Resistance

Jamaica: Reggae, Rice, and Resistance

Jamaica might be sold to the world as a postcard of turquoise water, all-inclusive rum punch, and basslines under the palms, but peel back the tourist gloss, and you find an island whose soul was tempered in rebellion, hunger, and the stubborn will to live free. Every beat of the drum, every sweetly sung Bob Marley lyric, every smoky curl of pimento-scented air, carries the aftertaste of struggle.

The story begins not with reggae or Rastafari, but on plantations and in the holds of slave ships.

The island, originally known as Xaymaca ("land of wood and water") by the indigenous Taino, was a fertile paradise long before European ships arrived. The Taino had a thriving culture, farming crops like cassava, sweet potatoes, and maize. Their peaceful existence was shattered in 1494 when Christopher Columbus landed, claiming the island for Spain. The Spanish enslaved the Taino, and within a few decades, their population was decimated by brutal labor, disease, and violence. The Spanish period, lasting over 150 years, was marked by the establishment of settlements and the introduction of crops like sugarcane, but it never developed into a major economic center for Spain. They also brought the first enslaved Africans to the island, though in relatively small numbers compared to the later British period. The Spanish presence left a lasting, though subtle, imprint on Jamaican culture, including place names and some agricultural practices.

In 1655, an English fleet, originally intended to capture Hispaniola, instead seized Jamaica from the Spanish with surprising ease. The remaining Spanish colonizers and their enslaved people fled into the mountainous interior, some of the enslaved people joining with the Taino, beginning the genesis of the Maroons, fortified free towns that made the British military bleed for every inch of land. For the English, Jamaica was a strategic prize. They transformed the island into a brutally efficient and immensely profitable sugar colony. To fuel the insatiable demand for labor, the British imported hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans through the transatlantic slave trade. This marked the true birth of colonial Jamaica as an economic powerhouse, a "jewel in the crown" of the British Empire, but one built on the unimaginable suffering of enslaved people. The rigid hierarchy of the plantation system was cemented, with a small number of white landowners at the top and a vast population of enslaved Africans at the bottom. This period solidified the racial and economic dynamics that would shape the island for centuries.

Of course, the maroon communities of free slaves continued to fight the British at every turn.

In 1739, the Crown signed a treaty to end a half-century of guerrilla war, granting the Maroons freedom in exchange for policing other runaways. It was a truce etched in smoke and suspicion, and from its embers came one of the island’s enduring symbols of freedom: jerk, meat buried in underground pits, crusted with Scotch bonnet and allspice, hidden from the eyes of the overseer.

From the late 18th century through the 19th century, a series of rebellions, including the Baptist War led by Sam Sharpe, ultimately led to the British government passing the Emancipation Act in 1834. While this officially ended chattel slavery, it did not dismantle the plantation economy or the deep-seated social inequities. The black majority continued to be bent under sugar and banana. The kitchens of the working poor became laboratories of resistance, stretching the starch of boiled yam and green banana to fill the gaps colonial wages left. Food here was never only to satiate hunger, it was improvisation as survival.

The period that followed was a long march toward self-governance and independence. Figures like Marcus Garvey in the early 20th century championed black empowerment and self-reliance, and his ideas fueled a growing sense of national identity. The widespread labor unrest of the 1930s, fueled by poverty and colonial oppression, was a watershed moment. It led to the formation of the island’s first major political parties and trade unions, laying the groundwork for a nationalist movement.

When banana workers downed their machetes in 1935, their hands were greased not with plantation fruit but with stamp and go, salted cod fritters fried at dawn, tucked into pockets bound for picket lines. Three years later, the 1938 Frome Estate sugar strike exploded into a nationwide uprising that birthed Jamaica’s modern labor movement. In the pockets of marchers: beef patties, yellow with turmeric, hard to crush in a crowd, hotter still with Scotch bonnet, portable proof that protest travels on a full belly.

The decades after WWII brought bauxite mines, cheap aluminum for foreign markets, and little change for the miners’ families. In zinc-roof kitchens, it was ackee and saltfish. a marriage of a West African fruit and preserved cod from the colonial trade, that kept bodies strong under the red dust of the pits.

Finally, after decades of growing political and social consciousness, Jamaica achieved full independence from the United Kingdom on August 6, 1962. This marked the official birth of the modern nation, but the journey was far from over.

Resistance took on a new rhythm in the 1960s and ’70s. Reggae emerged as the people’s newswire, carrying the words of Marcus Garvey and Walter Rodney over airwaves and sound systems. When the government barred Rodney from re-entering the country in 1968, students poured into the streets in the Rodney Riots. They ate rice and peas, Sunday food cooked on weekday mornings, because protest doesn’t wait for the weekend.

The 1980s brought “structural adjustment”, International Monetary Fund imposed austerity, and a sharp rise in food prices. In 1985, Kingston’s Bread Riots erupted over the basic right to eat. In the oil-slicked air of roadside fryers, festival, sweet fried dough, sizzled alongside the chants, an irony not lost on those who knew that even sweetness here was born of struggle.

To taste Jamaican food is to taste centuries of confrontation. So when the bassline drops and the grill lid closes, know that the fire under the pot is the same fire that’s lit the island’s resistance for 300 years, steady, smoky, and impossible to put out.

Jerk Chicken: Guerilla Smoke

Jerk Chicken is one of the world’s most instantly recognizable Jamaican dishes: dark, smoky, fiery, and flavorful to the bone. It’s become a symbol of island cuisine, sold at roadside stalls from Kingston to Montego Bay, but its roots run far deeper than modern menus. The word “jerk” likely comes from the Spanish charqui, meaning dried meat, but the technique is pure Maroon innovation, Africans who had fled the brutal plantation system and established free communities deep within Jamaica’s mountainous interior.

Originally, jerk wasn’t just a flavor, it was a method of survival. Maroon hunters would cure wild boar or goat using pimento (allspice), salt, and Scotch bonnet peppers, then slow-cook the meat over a low flame in smoke-concealed pits dug underground to avoid detection. It was stealth food. Resistance food. The forests of the Cockpit Country would carry the scent only so far, and the British would never find them in time.

That smoke would become the scent of rebellion.

By the early 1700s, Jamaica had become the crown jewel of Britain’s Caribbean sugar empire. But behind the wealth was a hellscape of labor: enslaved Africans toiled under unspeakable conditions on sprawling plantations, fueling the transatlantic economy. Many resisted in whatever small ways they could. Some fled entirely. These escapees became the Maroons, a term used for those who “marooned” themselves, vanishing into the interior. Over time, they formed organized, autonomous societies with their own leadership, governance, and defenses. Two main groups dominated: the Windward Maroons in the east, and the Leeward Maroons in the west. Led by formidable warriors like Queen Nanny, a spiritual and military genius, and Cudjoe, the leader of the Leeward faction, these communities became thorns in the side of colonial authority. British attempts to recapture runaways turned into drawn-out campaigns that saw entire regiments slaughtered, supply lines sabotaged, and troops demoralized.

The Maroons knew the land; they moved through the forests like shadows. Their tactics weren’t conventional, they were psychological. Quick ambushes, sudden raids, then disappear into the hills. British soldiers began calling it “bush war,” and they weren’t winning it.

By 1738, the British were desperate. The war had dragged on for decades. Sugar profits were shrinking, and troops were dying. In 1739, Governor Edward Trelawny authorized a peace treaty with Cudjoe’s Maroons. The treaty was unprecedented: it granted the Leeward Maroons 1,500 acres of land, political autonomy, and freedom in exchange for an uneasy peace. The Maroons would stop harboring new runaways and, controversially, help suppress future revolts.

It was a complicated, imperfect victory, but it was a victory nonetheless. Black people in the Caribbean had forced the British Empire to the negotiating table and secured legal recognition of their freedom.

And when the treaty was signed, they feasted.

Meat was dug from pits and served to warriors with smoke still rising off the bone. The pimento branches that had masked their fire in wartime now flavored celebration. Jerk chicken was no longer just to feed guerilla hunger, it had become a dish of the free. Every bite was a reminder of survival, of strategy, of sovereignty.

Today, jerk is often grilled in oil drums or over open flames instead of buried in pits, but the flavor profile remains unmistakable: fierce, hot, and smoky, with a depth that speaks of centuries. And though its popularity has gone global, its story remains rooted in resistance.

But the Maroon Peace Treaty was not the end of Jamaica’s fight for dignity. It was just the first treaty in a long war for justice. Nearly two centuries later, the descendants of enslaved Jamaicans would rise again, this time not in the forests, but in the banana fields of colonial plantations.

Note: Jerk chicken is spicy. Possibly the spiciest. I like spice, but you have been warned.

Jerk Chicken

Ingredients:

- 2–2.5 lbs chicken (bone-in thighs or drumsticks)

- 1 tbsp allspice

- 1 tsp dried thyme

- 1 tbsp brown sugar

- 1 tsp scotch bonnet powder

- 2 habanero peppers, minced

- 4 cloves garlic

- 1 thumb-sized piece of fresh ginger

- 1 small onion

- 3 scallions

- Juice of 1 lime

- 2 tbsp soy sauce

- 1 tbsp white or apple cider vinegar

- 2 tbsp vegetable oil

- Salt to taste

Instructions:

- Blend all marinade ingredients into a thick paste.

- Rub marinade all over chicken. Cover and refrigerate for at least 6 hours, ideally overnight.

- Grill on medium-high heat until charred and fully cooked (internal temp 165°F). Alternatively, bake at 400°F for 45–50 minutes, then broil for 3–5 minutes to char.

Stamp & Go: Strike Fritters

Stamp & Go is one of Jamaica’s oldest and most beloved street foods, a simple yet savory fritter made from salted cod, flour, and Scotch bonnet peppers. It’s quick to prepare, easy to carry, and packed with flavor. The name likely comes from 18th-century British naval slang: “Stamp and go!” was the command for sailors to move quickly, and these fried saltfish patties, quick to whip up and devour, became a go-to breakfast and snack for seafarers and working-class Jamaicans alike.

In the coastal villages of Jamaica, especially among fishmongers, dockworkers, and banana porters, Stamp & Go was a staple. It was the food of fishermen rising before dawn and of mothers feeding families on the cheap. By the early 20th century, it had become a deeply rooted part of the Jamaican diet, especially in rural areas where imported salted cod was one of the few consistent sources of protein. But in 1935, Stamp & Go became more than just breakfast. It became fuel for rebellion.

The global Great Depression of the 1930s devastated Jamaica’s fragile colonial economy. Banana exports, one of the island’s primary industries, plummeted in value. Meanwhile, wages stagnated or declined, and the cost of living rose. Banana workers, mostly Black Jamaicans laboring in the sun-drenched fields of Portland, St. Mary, and St. Ann, were often paid in script or tokens, rather than currency, redeemable only at plantation-owned shops. Exploited, voiceless, and hungry, they were primed for revolt.

In July 1935, that revolt came.

It began in Oracabessa, a small town on the north coast, known for its lush banana fields and quiet beaches. When news spread that the banana companies were cutting wages again, hundreds of workers walked off the job. Their demands were simple: better pay, decent conditions, and an end to company tokens. But they weren’t met with negotiations, they were met with silence.

So they made themselves heard.

The strike spread rapidly, fueled by word-of-mouth and community meetings. Roads were blocked, company power lines were cut, and small bridges sabotaged. Protestors formed picket lines and barricades using banana stalks and driftwood. Police were dispatched, and tensions boiled over. In one confrontation, batons were drawn. Violence erupted. Several workers were arrested. Others were beaten. Still, the strike held.

In those tense days, food was scarce, but Stamp & Go kept bellies full. Women fried batches in battered tin pots over open fires behind protest lines, distributing them wrapped in cloth or banana leaves. Saltfish was affordable and durable. Flour was cheap. These fritters didn’t need utensils, didn’t need tables, they could be eaten standing up, mid-chant, mid-march, mid-riot. Some were fried crisp and thin; others were thick and fluffy, with pepper seeds hidden in the dough like tiny sparks waiting to ignite.

Stamp & Go became a kind of edible badge, a humble fritter that symbolized solidarity, self-reliance, and resistance. It was working-class sustenance for a working-class struggle. Though the strike was eventually subdued by colonial forces, it sent a tremor through the system. The Oracabessa action was one of the first coordinated labor uprisings in the British West Indies and helped set the stage for the mass labor movements that followed.

Just three years later, a wave of unrest would erupt across the island, this time centered not in the banana fields, but in the burning heart of sugar country, where thousands of cane cutters would rise in open rebellion, demanding the dignity long denied to them.

I grew up on Rhode Island-style clam cakes, fried up at my grandma’s diner, with a secret family recipe passed down to the next generation. Stamp&Go reminded me of a spicier, saltier variety. It hit all the right notes.

Saltfish Fritters (Stamp & Go)

Ingredients:

- ½ lb salted cod, soaked and flaked

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 1/4 cup water (adjust as needed)

- ½ small onion, finely chopped

- 1 tomato or bell pepper, finely chopped

- 2 scallions, chopped

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- ½ tsp baking powder

- ½ tsp black pepper

- ½ tsp scotch bonnet powder

- ½ minced habanero pepper

- Oil for frying

Instructions:

- Mix flour, baking powder, and seasonings in a bowl.

- Stir in flaked cod, veggies, and just enough water to form a thick batter.

- Drop spoonfuls of batter into hot oil and fry until golden brown, about 3 minutes per side.

- Drain on paper towels and serve hot.

Jamaican Beef Patties: Pastries of the Picket Line

The Jamaican Beef Patty, golden and flaky on the outside, rich and spiced within, is as iconic as the island’s reggae rhythms. Influenced by Cornish pasties brought by British settlers, adapted with the bold seasonings of Indian and African cuisine, and often tinted yellow with turmeric or curry powder, the beef patty emerged as a uniquely Jamaican answer to laborer hunger. Cheap, portable, and deeply satisfying, it became a favorite of cane cutters, dock workers, and schoolchildren alike. By the 1930s, patties were sold by street vendors and shop windows from Kingston to Westmoreland, ubiquitous, affordable, and sustaining. But in May 1938, those patties found themselves on the frontlines of history.

Jamaica in the 1930s was a colony in crisis. The global depression had slashed prices for sugar and bananas, and the working class, largely Black, largely landless, bore the brunt of the suffering. Sugar estates paid pennies a day. Company stores overcharged for rice and flour. Housing was often no more than shacks of zinc and timber. Workers toiled from sunrise to dusk, with no unions, no protections, and no voice. That silence broke in Westmoreland.

On May 2, 1938, thousands of workers at the Frome Sugar Estate, one of the largest plantations in the country, walked off the job. It wasn’t just about wages. It was about dignity. Demands included better pay, basic sanitation, rest periods, and an end to beatings by overseers. The British authorities responded the way colonial empires often do: with batons and bullets. Police fired into crowds. Several workers were wounded. One, striking cane cutter A.G.S. Coombs, was shot and killed.

But the repression didn’t stop the movement, it ignited it.

News of the shooting spread across the island by radio, word of mouth, and the Gleaner newspaper. Workers in Kingston, Montego Bay, and Spanish Town walked out in solidarity. Riots erupted in the streets. Bridges were burned. Courthouses looted. Protesters waved palm leaves and placards, chanting for freedom and fair pay. Some waved signs bearing Marcus Garvey’s words; others simply waved empty hands, a symbol of the hunger they endured daily.

During this eruption of labor unrest, the beef patty took on new meaning; not just a meal, but fuel for the fight.

Vendors packed them by the dozen into cloth sacks and distributed them to marchers. Mothers made them in bulk, wrapping them in newspaper for sons heading to protest lines. The patty’s buttery crust kept it warm; its fiery filling gave strength. In a time when cooking fires were often out of reach and rations were short, the beef patty’s portability and punch made it an ideal meal for the picket line. Whether eaten cold or piping hot, it filled bellies during meetings, rallies, and marches.

The riots continued for weeks. British troops were deployed. More workers were arrested. In the end, over 30 people were killed across the island, with hundreds wounded or detained. But from the bloodshed and fire rose a movement that would reshape Jamaica.

Alexander Bustamante, a charismatic orator and postal clerk who had been writing letters in defense of workers for years, emerged as a key leader. He was arrested for sedition and spent time in prison, which only increased his popularity. Upon release, he founded the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union (BITU) in 1938, organizing tens of thousands of workers and transforming Jamaican labor politics. His cousin, Norman Manley, formed the rival People’s National Party (PNP). Together, they ushered in a new era of Jamaican nationalism, one that would eventually lead to universal suffrage (1944) and independence (1962).

But before constitutions and parliaments came the patty. Before ballots, there were bread crumbs.

On factory floors and sugar estates, the beef patty became part of the protest toolkit, wrapped in wax paper, stuffed in pockets, shared from hand to hand as both nourishment and symbol.

The patty fed revolution.

And while the 1938 riots reshaped Jamaica, they were only the beginning. In 1943, another group of workers, this time from the rapidly growing bauxite mining industry, would stage a strike of their own, testing the limits of the new labor order and pushing the island closer to the dream of self-determination.

It is important that when you shape the dough for the patty, you flatten it, and also do not be afraid to stuff it. The dough is suprisingly durable.

Jamaican Beef Patties

Dough:

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- ½ tsp salt

- 1 tsp curry powder or turmeric

- ½ cup cold butter or shortening

- ~½ cup ice water

Filling:

- ½ lb ground beef

- ½ small onion, finely chopped

- 2 scallions, chopped

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 tsp dried thyme

- 1 tsp allspice

- ½ tsp scotch bonnet powder

- 1 minced habanero pepper

- Salt and pepper to taste

- ¼ cup breadcrumbs (or crushed crackers)

- ¼ cup water or beef broth

Instructions:

- Filling: Sauté onion, garlic, and scallion in oil. Add beef and spices, cook until browned. Stir in water and breadcrumbs, cook until thick. Cool.

- Dough: Mix flour, salt, and turmeric. Cut in butter until crumbly. Add water and form dough. Chill 30 mins.

- Roll dough into 6-inch circles. Add filling, fold and seal with a fork.

- Bake at 375°F for 25–30 minutes until golden.

Ackee and Saltfish: Breakfast Before the Barricades

Creamy, buttery ackee, Jamaica’s national fruit, paired with the salty, savory flakes of preserved cod, creates a dish that’s as much a paradox as the island’s history itself. Ackee and Saltfish is more than just a national dish, its the story of Jamaica; a dish of survival, colonial legacy, and creole invention. Ackee was brought from West Africa in the 18th century, traveling across the Middle Passage like so many of the enslaved who would come to see it as a taste of home. Saltfish, on the other hand, came from the cold Atlantic, imported by British merchants as cheap protein to feed enslaved laborers on sugar plantations. The pairing was never about luxury, it was about necessity. But out of that necessity grew tradition, creativity, and ultimately, identity.

By the 20th century, ackee and saltfish was no longer food for the enslaved, it was food for everyone. It filled the bellies of schoolchildren in rural Clarendon, sat on the breakfast tables of Kingston laborers, and warmed pots in bauxite mining towns like Mandeville, Brown’s Town, and Discovery Bay. It was cheap to make, rich in calories, and full of flavor, especially when cooked with onions, scotch bonnet peppers, thyme, and tomatoes. It tasted like home.

And in 1943, as Jamaica's economy shifted from sugar to bauxite, it became a food of resistance.

Bauxite, the mineral from which aluminum is extracted, was discovered in commercial quantities in Jamaica in the 1940s. The timing was no accident, World War II had pushed demand for aircraft and industrial metals to all-time highs. U.S. and Canadian companies rushed to develop mines in the parishes of St. Ann, Manchester, and St. Elizabeth, transforming sleepy farming villages into industrial extraction zones. Roads were paved. Plants were built. Contracts were signed.

But for the men who dug the red dirt, little changed.

Most bauxite workers were rural Jamaicans, many of them landless peasants who had left sugar estates or small-scale farming in search of a better life. What they found instead was exploitative wages, long hours, and foreign bosses who treated them no better than their grandfathers had been treated in the cane fields. There was no electricity in their villages. No running water. Their families lived in zinc-roofed board houses while trains filled with ore thundered past on the way to the coast.

Still, they worked. They woke before dawn. They boiled water. They salted down cod. They chopped ackee pods that had ripened overnight. Their wives or sisters would prepare it all in large iron pots, stirring the yellow fruit gently, so it wouldn’t break apart. By the time they left for the mines, they had a portion packed in calico cloth or a reused tin. It was filling, it was home-cooked, and it reminded them that though they labored for others, they still owned their morning.

But frustration was rising. In July of 1943, the tension boiled over.

A group of miners in Kirkvine, Manchester walked off the job, demanding higher wages, paid overtime, and safer working conditions. They had no formal union representation, and no legal protections. Their strike began small, just a few dozen, but word spread quickly across the island’s growing labor network, bolstered by the organizing work of the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union (BITU). Within days, hundreds more joined from other mining communities.

The government, still a British colonial administration, dismissed the workers’ complaints. When workers blocked roads and picketed mine entrances, police were sent in. Clashes broke out. Several workers were beaten and arrested. But still they refused to return.

It wasn’t just about pay, it was about power.

At nightly meetings held under street lamps and in schoolyards, workers shared meals and stories. Ackee and saltfish, cooked in bulk by women who supported the strike, was a constant presence. It was handed out in foil packets, ladled onto shared plates, or eaten straight from enamel bowls. And as the miners talked about rights, about respect, about the future of Jamaica, they ate this dish, born from slavery, turned into a symbol of survival.

Eventually, the strike forced the government and mining companies to negotiate. Though immediate gains were limited, the 1943 Bauxite Strike marked a turning point. It strengthened labor unions, raised awareness of corporate exploitation, and gave rural Jamaicans a voice in shaping their destiny. Many of the same organizers would go on to campaign for universal adult suffrage, won just a year later in 1944.

Ackee and saltfish remained on their tables, and in their hearts; the food brought to the picket line when they decided to stand up.

And though labor rights had been won on paper, real liberation, cultural, educational, economic, was still on the horizon.

Ackee and saltfish deceptively looks like scrambled eggs. Its taste though. Its taste is unlike anything I’ve ever had before.

Ackee and Saltfish

Ingredients:

- ½ lb salted cod

- 1 can ackee (or equivalent fresh, if available)

- ½ onion, thinly sliced

- 1 tomato, diced

- 1 bell pepper, sliced

- 2 scallions, chopped

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- ½ tsp thyme

- ½ tsp scotch bonnet powder

- 1 minced habanero pepper

- 2 tbsp vegetable oil

Instructions:

- Soak salted cod in cold water overnight or boil 10–15 minutes, changing water twice. Flake.

- In a pan, heat oil and sauté onion, garlic, bell pepper, scallion, and tomato.

- Add cod, thyme, and both chilis. Cook for 5 minutes.

- Gently fold in ackee. Cook until heated through. Do not stir too much (ackee is delicate).

Rice and Peas: Rasta Rice

A pot of rice and peas is almost as synonymous with Jamaica as the reggae rhythm or the green in the flag. Despite the simplicity of the name, it’s far from plain. Creamy kidney beans, called “peas” in Jamaican parlance, are simmered with rice in coconut milk, fresh thyme, scallions, and allspice berries. Scotch bonnet adds heat. Garlic deepens the flavor. Often eaten alongside oxtail, jerk chicken, or fried fish, rice and peas is the foundation of a Sunday dinner, but also the base of a weekday meal, or the only warm food on a low-income table.

Its origins lie in West Africa, where rice and beans have long been cooked together for sustenance and celebration alike. During the transatlantic slave trade, enslaved Africans carried these culinary traditions with them to the Caribbean, adapting to the island’s ingredients and colonial constraints. Coconut milk replaced palm oil. Thyme joined the pot. And slowly, a new identity took root; one that blended African tradition with Jamaican resilience.

By the 20th century, rice and peas had become everyone’s food: Rastafari ital adherents ate it meatless. Laborers packed it in tins to bring to work. Housewives stretched it across large families. Middle-class families ate it dressed up with beef or pork. It was inclusive, economical, and emblematic of shared survival; the perfect symbol for what would become one of Jamaica’s most galvanizing uprisings.

On August 6, 1962, Jamaica gained its independence from the United Kingdom, transitioning from a colony to a sovereign nation. However, this newfound independence didn’t immediately dismantle the deep-seated social and economic inequalities inherited from colonial rule. The Rastafarian movement, which emerged in the 1930s, became a powerful voice for the marginalized. Rooted in an Afrocentric worldview, Rastafarianism championed black identity and opposed the systemic oppression and class divisions that persisted in post-colonial Jamaica. Rastas saw Ethiopia as a symbol of black liberation and Hailie Selassie I, its emperor, as a divine figure. Their beliefs and counter-cultural lifestyle, which included dreadlocks and the use of ganja for spiritual purposes, often put them at odds with the conservative Jamaican government and society, while being linked with the reggae music scene which was growing in popularity.

In October 1968, a scholar named Dr. Walter Rodney returned from attending a Black Writers’ Congress in Montreal. Rodney, a young Guyanese academic teaching at the University of the West Indies (UWI) in Mona, had been giving weekly lectures off-campus, often in Kingston’s poor neighborhoods and Rastafarian communities. He spoke of African liberation, Marxist history, and postcolonial identity. He challenged capitalism, colonialism, and the hypocrisy of newly independent Caribbean governments that still catered to foreign interests. The Rastafarian movement's rejection of the neo-colonial status quo created a fertile ground for these ideas.

Rodney wasn’t just speaking to students, he was speaking to ghetto youth, domestic workers, market vendors, and ganja farmers. And they listened.

But the Jamaican government, led by Prime Minister Hugh Shearer, didn’t like what they heard. They saw Rodney’s ideas as dangerous. Subversive. Radical. When Rodney tried to re-enter Jamaica from Canada on October 15, he was denied entry. No explanation. No trial. Just a ban, and an attempt to silence his voice.

It had the opposite effect.

The next day, students at UWI walked out of classes in protest. Then they marched. Through Mona. Down Old Hope Road. Into Kingston. Hundreds joined them. Then thousands. Rastafarians. Trade unionists. Street vendors. Schoolteachers. Unemployed youth. The lines between student and street blurred as discontent boiled over. They marched to the Ministry of Home Affairs, demanding answers.

The police responded with tear gas and batons. Protesters responded with bricks and bottles.

It became known as the Rodney Riots.

Fires were lit in the streets. Barricades went up near Cross Roads. Stores were looted. Cars were flipped. The capital descended into chaos, but underneath the chaos was clarity: this wasn’t just about a scholar. It was about who had the right to speak. To learn. To demand better. In a Jamaica just six years into independence, the people were asking: whose freedom was this, really?

Amid the unrest, rice and peas remained on the table. In university dormitories, it was stretched to feed the students who chose protest over class. In downtown homes, women cooked it for neighbors taking shelter or coming back from the march. In Rasta camps, it was served with steamed callaloo and coconut water to keep spirits grounded and bellies full. The dish was familiar, hearty, and shared; the kind of food that could feed a revolution without saying a word.

Rodney, meanwhile, didn’t disappear. His banning made him a symbol. He would go on to write “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”, one of the most influential anti-colonial texts of the 20th century. He continued to teach, to organize, to resist, until his assassination in Guyana in 1980 under suspicious political circumstances.

But the Rodney Riots planted something permanent. They gave rise to a more conscious youth movement, a sharper critique of class and race, and an enduring connection between Jamaican intellectual life and grassroots resistance. In the years to come, radical thinkers, dub poets, and reggae artists would carry his message forward, from Mutabaruka’s verse to Burning Spear’s basslines.

And when food was shared at meetings, at reasoning sessions, at Nyabinghi gatherings, it was often rice and peas that warmed the pot. It was the people's dish.

But economic inequality didn’t go away. If anything, the 1970s brought new instability, rising prices, IMF loans, food shortages. By 1985, the cost of flour and rice spiked, triggering yet another wave of protest. That year, in what became known as the Kingston Bread Riots, the people once again took to the streets, this time, not for ideas, but for food itself.

There are multitudes of ways to prepare Rice and Peas. I used Pigeon Peas and rice cooked in coconut milk, leading to an almost white, creamy finished product.

Rice and Peas

Ingredients:

- 1 cup long grain rice (jasmine or basmati)

- 1 can (15 oz) kidney beans or gungo peas, drained

- 2 cups coconut milk

- 1 cup water

- 2 garlic cloves, smashed

- 2 scallions

- 2 sprigs fresh thyme (or 1 tsp dried)

- 1 whole habanero pepper (do not cut)

- ½ tsp salt (or to taste)

- Optional: ¼ tsp scotch bonnet powder for extra heat

Instructions:

- In a pot, combine coconut milk, water, garlic, scallions, thyme, beans, salt, and whole habanero pepper.

- Simmer for 10 minutes to infuse flavor.

- Add rice, stir once, then cover and simmer on low for 18–20 minutes until liquid is absorbed.

- Remove habanero before serving.

Festival Bread: Structural Adjustment and Sweetness

Festival bread, golden, crisp-edged, and sweet, might seem like a street snack, a cheerful accompaniment to fried fish or jerk pork wrapped in foil at a beachside stand. But it’s also a story; one that blends West African culinary tradition with the improvisation of Jamaica’s urban poor. Made from a humble mix of cornmeal, flour, sugar, and baking powder, deep-fried until crisp and golden, festival is soft on the inside, crunchy on the outside, a culinary metaphor for the Jamaican spirit: toughened by hardship, yet deeply warm and hopeful within.

Its roots lie in African dumpling traditions brought over by enslaved people, who stretched simple starches with whatever was available. Over time, these evolved into johnnycakes, bammy, and eventually, festival. The name itself is aspirational: even in scarcity, people found ways to celebrate flavor. Festival was sweet but not rich, filling but not fancy. It was the kind of thing you could make with a few scoops of dry goods, oil from a reused bottle, and nothing more than a hot pan or a roadside vendor’s vat. And in 1985, that simplicity became essential.

That year, Jamaica was starving, not just for food, but for justice.

After independence in 1962, Jamaica had danced between two dominant political forces: the democratic socialist People’s National Party (PNP) and the more conservative, business-friendly Jamaica Labour Party (JLP). By the 1970s, the global economy was in crisis. Oil prices skyrocketed. Interest rates soared. And Jamaica, like many post-colonial nations, found itself in debt.

In the name of economic stabilization, Jamaica turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). But the help from the IMF, also known as the global capital’s loan sharks, came with strings; austerity measures that slashed public spending, eliminated food subsidies, and devalued the Jamaican dollar. These “Structural Adjustment Programs” were supposedly to bring balance. Instead, they brought breadlines.

By the time Edward Seaga’s JLP government was deep into its IMF partnership in 1985, the working class could feel the consequences. Prices on staple goods like flour, rice, and bread rose faster than wages. Imported foods became luxuries. Jamaican families who once made rice and peas or fried plantain with ease now had to ration salt, sugar, and oil. Even water access in some neighborhoods became unreliable.

It came to a head in May 1985, when the government announced another price hike on essential items, including flour and bread. The response was swift. Working-class youth, vendors, domestic workers, and unemployed men and women took to the streets of Kingston, blocking roads with debris, burning tires, and setting up makeshift barricades along Spanish Town Road and Half Way Tree.

At first, they demanded a rollback of prices. But as police clashed with protesters, the demand grew louder: affordable food, better wages, real independence.

Festival bread was there, not as a banner, but as a lifeline.

Street vendors, many of them single mothers, kept selling hot festival wrapped in brown paper near protest sites, using cornmeal and sugar from what they could scrape together. Festival was cheap to make, easy to carry, and warm enough to keep people going. Whether eaten on the walk to work, the march to Gordon House, or crouched behind an overturned barrel, festival became part of the riot’s rhythm, a sweet bit of survival in sour times.

For the protestors, it wasn’t just about hunger. It was about dignity. About being told for decades to “tighten your belt,” while politicians wore imported suits and rode in tinted cars. It was about seeing foreign-owned companies profiting while Jamaican children went to school hungry. One placard read simply: “We cyan eat IMF.”

The Bread Riots lasted for days. Police and military were deployed. Several people were injured. At least one protester was killed. In the aftermath, the government paused some price increases, but the austerity policies stayed. The IMF loans continued. So did the hunger.

Yet the people remembered. The riots marked a turning point. not in policy, but in consciousness. Jamaica’s poor, already radicalized by the teachings of Walter Rodney and the Rasta movement carried on the soundwaves of reggae music, now understood something deeper: poverty was not an accident, it was enforced.

Festival bread outlived the barricades. It continued to be sold on corners, eaten at beaches, fried in homes, and served with fish by the dozens at Hellshire and Boston Bay. But for those who were there in ‘85, each bite still carried memory, not just of sweetness, but of survival.

Festival bread might be sweet, but if you want to get real wild…. Add hotsauce and feel the twist of flavors dance in your mouth.

Festival (Sweet Fried Dough)

Ingredients:

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 1/3 cup fine cornmeal

- 2 tbsp sugar

- 1 tsp baking powder

- 1/4 tsp salt

- ½ cup water or milk (more if needed)

- Oil for frying

Instructions:

- Mix flour, cornmeal, sugar, baking powder, and salt in a bowl.

- Slowly add water or milk and knead into a soft dough.

- Divide into small ovals or logs.

- Fry in hot oil (350°F) until golden brown and puffy, about 3–5 minutes per side.

- Drain on paper towels. Serve hot.

Comments

Post a Comment