USA: The Unfinished Feast

USA: The Unfinished Feast

“This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

—Frederick Douglass, What to the Slave is the Fourth of July? (1852)

Each year on the Fourth of July, fireworks erupt across the sky in celebration of America’s birth. But as Douglass reminded us more than 170 years ago, the promise of freedom has never been equally shared. The Declaration of Independence was not a conclusion, it was a contradiction, a spark struck in soil still soaked with inequality.

America’s story isn’t one of finished triumph but of ongoing reckoning. From the Boston Massacre to the American Indian Movement, from suffragette teas to immigrant labor strikes, every region bears its battle scars, and its recipes. Food has long been a witness to protest and a companion to righteous rage. It is both survival and celebration, a shared language in moments of scarcity and resistance.

This year, we mark the holiday by turning the table into a tribute. The Unfinished Feast serves ten dishes tied to ten pivotal movements, each one a taste of revolution from a different corner of the country. Some are spiced with rebellion, others sweetened with hope. Together, they tell the story of a nation still becoming.

We begin with Boston Baked Beans and the question posed by scholars and skeptics alike: Was the American Revolution a working-class revolution? Cornbread follows, a staple that fed abolitionists, Underground Railroad conductors, and the bleeding edge of Bleeding Kansas. We serve Frybread, reservation food born of displacement and resistance, alongside stories of the Navajo Long Walk and Indigenous sovereignty. There’s Suffragette Punch, a citrusy fundraiser drink that helped win the vote for half a nation, those who had long been denied a voice in its direction.

We ladle out Brunswick Stew, the “struggle meal” of Appalachian coal miners who stood their ground at Blair Mountain. We simmer Collard Greens, a cornerstone of African American soul food, cooked in the same pots that fed Civil Rights marchers walking the long road to justice. We sizzle up Fajitas, born from castoff cuts given to Mexican-American ranch hands, while tracing the long shadow of anti-immigrant crackdowns and the movements that pushed back.

Avocado Eggs Benedict, a dish of drag brunches and queer joy, reminds us how the LGBTQ+ movement turned pain into defiant celebration. Chicago-Style Hot Dogs, loaded with toppings and symbolism, bring us to the first Special Olympics and the ongoing fight for disability rights. And we close with Poke Bowls, Hawaiian cuisine entering the mainstream just as Native Hawaiians demand their own stories be heard.

So light the grill. Pass the cornbread. And taste the fight for a more perfect union. The feast remains unfinished. The work, still simmering.

New England- Boston Baked Beans: Fueling the Revolution

Long before brick townhouses lined the Charles River, the Wampanoag and other Native peoples slow-cooked beans in clay pots buried under smoldering coals. They sweetened them with maple syrup and thickened them with bear or deer fat, letting time meld the flavors. When Puritan settlers arrived in the 1600s, they adopted this method to survive brutal winters and strict Sabbath laws banning Sunday cooking. Their beans simmered overnight in iron pots, ensuring a hot meal without breaking holy rules. But it was the workers, the dockhands, carpenters, and seamstresses, who turned Boston Baked Beans into a gritty legend of rebellion. By the mid-1700s, molasses from the Caribbean slave trade, cheap but stained with blood, replaced maple syrup. Salt pork, tough but filling, melted into the pot, creating a smoky, sticky staple. Its scent drifted through Boston’s North End alleys, earning the city its nickname: Beantown.

In smoky taverns like the Green Dragon, laborers with calloused hands and empty pockets shoveled beans from dented tin plates. They cursed the Stamp Act of 1765, which taxed their papers, the Quartering Act forcing them to house British soldiers, and the Townshend Duties of 1767 draining their meager wages. These taxes bled their earnings dry while they hauled cargo, hammered nails, or stitched sails from dawn to dusk. Beans were cheap, filling, and could simmer all day, fueling the rabble who worked the docks, shops, and streets of a city on edge. In 1770, tensions erupted. British soldiers fired on a crowd of protesters in the Boston Massacre, killing five, including Crispus Attucks, a dockworker of African and Native descent. His blood on the cobblestones sparked rage across the colonies. Samuel Adams, a firebrand rallying the masses, knew the real fire burned in the hearts of workers crushed by colonial greed.

Who powered the American Revolution? Historians clash over the question. Howard Zinn argued it was the raw fury of laborers, dockhands, coopers, and farmers, their backs bent under imperial weight. Bernard Bailyn credited the lofty ideals of elites in powdered wigs who penned manifestos. The truth lies in the mix of sweat and ink, molasses and muskets, fermenting side by side. Carpenters hauled timber for protest scaffolds in sweltering summers. Printers set radical pamphlets in dim, ink-stained shops. Blacksmiths forged tools for liberty in sweat-soaked shirts. Enslaved men joined militias, risking death for a freedom rarely granted. Women spun thread to boycott British cloth, their fingers raw from endless work. Tenant farmers rioted in the Hudson Valley, demanding land and bread. Beans fed them all, simmering in iron pots while they plotted resistance in taverns, sewing circles, and dockside huddles.

When the war ended in 1783, victory favored the elite. The new Constitution of 1787 reserved power for property-owning white men, leaving laborers with little. Soldiers returned to foreclosure notices and crushing debts, sparking uprisings like Shays’ Rebellion in 1786, led by farmers fed up with broken promises. Thomas Paine, whose Common Sense of 1776 had stirred the masses to revolt, was shunned for demanding a revolution that reached beyond wealthy drawing rooms. The molasses in those beans, tied to the triangular trade, came from enslaved hands in Caribbean fields. It was a bitter reminder of the wealth built on stolen lives and labor, a system that propped up the new nation’s economy while workers struggled.

Every spoonful of Boston Baked Beans carries this layered history: Wampanoag ingenuity, workers’ rage, colonial exploitation, and revolutionary fire. They nourished dockworkers starving British ships through boycotts, women weaving defiance in sewing circles, and fighters dragging cannon to Dorchester Heights in 1776 to drive the British out. Today, as workers face low wages, union-busting, and corporate greed, these beans remind us the fight for a fair share is as old as the Revolution itself. So ladle them up this Fourth of July. Taste the struggle of the rabble who built a nation, one gritty bite at a time. The flame still burns. Boston Baked Beans are no canned mush. They are hearty, complex, and born of sweat.

Boston Baked Beans

- Description: A sweet, hearty dish rooted in Wampanoag tradition, adapted by Puritan settlers with molasses and salt pork, fueling revolutionary debates in colonial Boston.

- Yields: 6–8 servings

- Prep Time: 15 minutes (plus overnight soaking)

- Cook Time: 6–8 hours

Ingredients:

- 1 lb navy beans, dried

- ½ lb salt pork, diced

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- ½ cup molasses

- ¼ cup brown sugar

- 1 tsp dry mustard

- 1 tsp salt

- ½ tsp black pepper

- 4 cups water

Instructions:

- Soak beans in water overnight; drain and rinse.

- In a Dutch oven over medium heat, sauté salt pork until fat renders, about 5 minutes. Add onion and cook until softened, about 5 minutes.

- Stir in beans, molasses, brown sugar, dry mustard, salt, pepper, and water. Bring to a boil.

- Reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer for 6–8 hours, stirring occasionally, until beans are tender and sauce is thickened. Add water if needed to prevent drying.

- Serve warm, ideally with cornbread.

Tips:

- For a vegetarian version, omit salt pork and use 2 tbsp vegetable oil, adding 1 tsp smoked paprika for flavor.

- Check beans at 6 hours; cooking time varies based on bean age and pot type.

Great Plains- Cornbread and Freedom

Long before settlers crossed the Mississippi, Native nations like the Cherokee, Sioux, and Iroquois turned maize into a lifeline. Through nixtamalization, soaking corn in an alkaline solution, they unlocked its nutrition and ground it into flatbreads, porridge, and dough that sustained body and soul. Hungry European migrants, often desperate and unprepared, adopted these methods to survive the harsh plains. They learned corn could be mashed into a quick, yeast-free loaf, cheap to make, able to feed a crowd, and sturdy enough to carry in saddlebags. By the 1800s, cornbread became the bread of the defiant, a gritty staple fueling farmers, preachers, and runaways in the bloody fight against slavery in the Great Plains.

Slavery was America’s deepest wound, a fracture the founders papered over with compromises rather than healed. The Constitution sidestepped naming it, yet protected it. The Senate, giving equal weight to every state, became a chamber where justice stalled. For decades, deals like the Missouri Compromise of 1820 balanced free and slave states, delaying the inevitable clash. But the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 tore that balance apart. It repealed the Missouri Compromise, letting settlers in Kansas and Nebraska decide slavery’s fate through popular sovereignty. The idea sounded democratic. In practice, it was a call to war. Pro-slavery “Border Ruffians” from Missouri flooded Kansas, rigging votes with guns and fists. Abolitionists, often poor farmers, preachers, and teachers organized by groups like the New England Emigrant Aid Company, rolled west with rifles, pamphlets, and cornbread in their sacks. Kansas became a battleground, its prairies stained with blood.

Farmers, their hands cracked from plowing rocky soil, hauled cornbread and supplies to Free-State militias, risking their lives for a cause bigger than their fields. Women, their aprons dusted with cornmeal, baked skillet after skillet in crude hearths, sending “journey cakes,” dense and durable, to feed fighters and protesters. These were not just meals. They were lifelines, baked by calloused hands after 14-hour days, carried through mud to militia camps, and shared by those who knew a posse might ride up any minute. In 1856, Bleeding Kansas exploded. A pro-slavery mob sacked Lawrence, smashing printing presses and torching homes. Days later, John Brown, a fiery abolitionist, led the Pottawatomie Massacre, dragging five pro-slavery settlers from their cabins and hacking them to death with swords. Guerrilla skirmishes at Black Jack, Osawatomie, and Hickory Point scarred the plains, a grim rehearsal for the Civil War. Cornbread fueled it all, baked fast over campfires by farmers, radicals, and outlaws who defied the law to end slavery.

The Underground Railroad left its crumbs too. Conductors, often Black women and freedmen scraping by, packed cornbread for runaways dodging slave catchers through prairie nights. Enslaved people, underfed and hunted, carried these dense slices in cloth, a meager shield against starvation. In safe houses, where fear hung heavy, a warm slab of cornbread was often the first real meal in days, shared by trembling hands with a whisper: you made it this far. Two rival governments emerged in Kansas. The pro-slavery Lecompton regime drafted a constitution enshrining bondage, backed by Missouri’s armed thugs. The Free-State Topeka government, built by farmers and abolitionists, declared it illegitimate and begged Congress for recognition. Both claimed statehood. Both sent delegations to Washington. Neither trusted the other to back down.

John Brown survived Kansas but not Harpers Ferry. In 1859, he led a doomed raid on the federal armory in Virginia, hoping to arm the enslaved for a mass uprising. Captured, convicted of treason, and hanged, he became the first person executed by the federal government for trying to end slavery. Northern workers, from factory hands to dockworkers, mourned him as a martyr. Southern planters saw his ghost in every shadow, fearing rebellion. As the nation lurched toward war, soldiers marched to “John Brown’s Body,” their bellies filled with cornbread from abolitionist kitchens. This was not just food. It was rebellion, born from Native ingenuity, baked by farmers’ weary hands, and carried by runaways. Today, as workers battle wage theft and activists fight systemic inequity in food deserts and beyond, cornbread still graces picket lines and community tables. It reminds us justice is built from the ground up. So bake it this Fourth of July. Taste the defiance of those who fought for a better nation. Freedom rises slow, but it rises.

Cornbread

- Description: A simple, sustaining staple from Native American maize traditions, fueling abolitionists and Underground Railroad conductors in Bleeding Kansas.

- Yields: 9 servings (8x8-inch pan)

- Prep Time: 10 minutes

- Cook Time: 20–25 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1 cup cornmeal

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- ¼ cup granulated sugar

- 1 tbsp baking powder

- ½ tsp salt

- 1 cup milk

- ¼ cup vegetable oil

- 2 large eggs

Instructions:

- Preheat oven to 400°F (200°C). Grease an 8x8-inch baking pan.

- In a large bowl, whisk together cornmeal, flour, sugar, baking powder, and salt.

- In a separate bowl, whisk milk, oil, and eggs until combined.

- Pour wet ingredients into dry, stirring until just combined (do not overmix).

- Pour batter into prepared pan and bake for 20–25 minutes, until golden and a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean.

- Cool slightly, cut into squares, and serve warm.

Tips:

- For a richer flavor, use buttermilk instead of milk.

- Add ½ cup corn kernels or ¼ cup diced jalapeños for texture and spice.

Mountain West - Frybread: Crumbs of Resistance

In 1864, the U.S. Army ripped 10,000 Navajo and Mescalero Apache from their homelands, forcing them on the Long Walk, a 300-mile trudge through snow and dust to Bosque Redondo, a barren internment camp in what is now eastern New Mexico. Soldiers burned their crops, slaughtered their livestock, and razed their homes. Up to 3,500 died, their bodies left in ditches from starvation, cold, or disease. No corn grew in that wasteland. No squash or beans. The government tossed them rations: white flour, rancid lard, salt, and sugar, scraps meant to break their spirits and keep them chained to settler supply lines. Navajo women, their hands raw from grief and labor, kneaded this meager haul into dough, flattened it with weathered palms, and fried it in sizzling lard over makeshift fires. Frybread was born, a gritty defiance against starvation. It was not their ancestors’ rich diets of game and harvests, but it kept children breathing, bellies filled, and hope alive amid colonial brutality.

From those scarred hands, frybread became the Mountain West’s heartbeat, pulsing from Navajo mesas to New Mexico pueblos, from Ute lands in Colorado to Shoshone territory in Utah. At rodeos, chapter houses, and protest camps, it was served with red chile, elk, or wojapi berry sauce, its golden crust a testament to survival. In Shiprock, Tuba City, and Window Rock, women fried it in iron skillets, feeding families and fueling resistance. This was not just food. It was a middle finger to empire, proof that Navajo mothers could turn scraps into sustenance for a people who refused to vanish, their resilience as hot as the oil that cooked it.

This defiance echoed through generations. In 1973, Oglala Lakota and American Indian Movement fighters occupied Wounded Knee, on ground where U.S. troops butchered over 250 Lakota in 1890. For 71 days, they faced federal rifles, demanding justice for broken treaties. Women, their aprons stained with soot, fried dough over campfires, passing frybread through barricades to feed hungry fighters. In 1969, Indigenous rebels seized Alcatraz, reclaiming it under treaty rights. For 19 months, frybread sizzled in camp kitchens, nourishing their stand. In 1972, the Trail of Broken Treaties caravan rolled to Washington with a 20-point sovereignty plan, frybread shared among marchers under starlit skies. In 2016, at Standing Rock, water protectors battling the Dakota Access Pipeline ate frybread with stew, their frostbitten hands clutching dough that warmed their fight.

Frybread carries scars. Its ingredients, white flour, lard, sugar, are colonial shackles, tied to forced dependence and health crises like diabetes and heart disease ravaging Native communities. To some, it is a sacred tradition, its sizzle linking elders to children across dusty kitchen tables. To others, it is a bitter reminder of stolen lands and diets. Navajo women, laboring in camps and kitchens, made it a weapon of survival, but its weight lingers. Now, Indigenous chefs at The Fry Bread House in Phoenix and Sakon Restaurant on the Navajo Nation reimagine it, pairing it with wild greens, local berries, and stories of food sovereignty. It graces funerals, fundraisers, protests, and feasts, a ledger of loss and unbreakable will.

In the Mountain West, the struggle endures. From Bears Ears to uranium cleanup, Indigenous workers, organizers, and families fight for land, water, and dignity. Frybread fuels them, kneaded by elders recounting Bosque Redondo’s horrors, fried by youth learning their people’s fire. Today, as Native workers battle wage theft and poisoned rivers, frybread nourishes protests, from Standing Rock to reservation pickets. It is no mere bread. It is defiance, born from trauma, shaped by calloused hands, sizzling with rage. So fry it this Fourth of July. Taste the struggle of a people who endure, their spirit unbowed. They are still here.

Frybread

Description: Born of necessity during the Navajo Long Walk, frybread transforms government rations into a symbol of Indigenous resilience and resistance.

Yields: 8 pieces

Prep Time: 15 minutes

Cook Time: 15–20 minutes

Ingredients:

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 tbsp baking powder

- ½ tsp salt

- 1 cup warm water

- Vegetable oil, for frying (about 2 cups)

Instructions:

- In a large bowl, mix flour, baking powder, and salt.

- Gradually add warm water, stirring to form a soft dough. Knead lightly until smooth, about 2 minutes.

- Divide dough into 8 equal balls. Flatten each into a ¼-inch thick disk (about 5–6 inches wide).

- Heat 1 inch of oil in a deep skillet to 350°F (175°C).

- Fry each disk for 1–2 minutes per side until golden brown. Drain on paper towels.

- Serve warm with honey, powdered sugar, or chili.

Tips:

- For Indian tacos, top with seasoned ground beef, beans, lettuce, and cheese.

- Ensure oil is hot to avoid greasy frybread; use a thermometer if possible.

Mid-Atlantic: Suffragette Punch: Shaken and Stirred

In the gritty streets of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, Suffragette Punch, a sharp, fizzy citrus brew, fueled the fight for women’s votes. It was no delicate sip for polite society. It was a liquid rebellion, poured by seamstresses, factory workers, and maids in smoky union halls and church basements, their hands cracked from scrubbing floors or stitching cloth. In 1848, the Seneca Falls Convention in upstate New York sparked the movement. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, enraged by their exclusion from the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, drafted the Declaration of Sentiments, demanding the ballot and full citizenship. Their words ignited a fire under working-class women, who stirred punch in dented tin bowls, plotting democracy’s next steps between grueling 12-hour shifts in sweatshops and tenements.

The Mid-Atlantic was a crucible of sweat and defiance. New Jersey, where women briefly voted before 1807, saw its 1915 suffrage referendum crushed, a blow that stoked fiercer organizing among shop girls, laundresses, and mothers scraping by. In Pennsylvania, Rose Schneiderman, a cap maker with fire in her throat, poured punch in cramped union halls, rallying workers across class lines to demand wages and votes. Philadelphia’s church basements buzzed with the tang of lemon, sugar, and raw hope, as women, their fingers raw from sewing or washing, mixed punch amid plans for pickets and arrests. In 1913, Alice Paul, a New Jersey Quaker toughened by London’s militant suffrage, led the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Thousands marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, braving jeers, hurled bricks, and police neglect. They pushed forward, sashes torn, fists clenched, their courage forged in the face of violence.

Black suffragists, like Ida B. Wells, Mary Church Terrell, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, were shoved aside by white organizers. In 1913, Wells was told to march at the back of the D.C. procession. She refused, striding forward with her Chicago sisters, her resolve hard as iron. Black women, often domestics or teachers living on pennies, built their own networks in church circles, women’s clubs, and NAACP chapters. They served punch as fuel for a double fight against sexism and racism, their glasses clinking in defiance of exclusion. In 1917, New York’s suffrage referendum passed after decades of sweat, with punch bowls gleaming in the bitter November chill, a victory bittersweet for those still denied a seat at the table.

The punch bowl held grit and contradiction. Its tart fizz mirrored the rage of women stirring it after crushing days in factories or classrooms. Its shared sips bound immigrants, workers, and Black activists in cities like New York and Philadelphia, where class and race collided in crowded tenements. After the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, the fight pressed on for labor reform, civil rights, and reproductive freedom, with Mid-Atlantic hubs alive with plans over punch. Today, as voter ID laws, felony disenfranchisement, and an unratified Equal Rights Amendment choke democracy, Suffragette Punch flows at Women’s Marches and community cookouts. It is no mere drink. It is the underdog’s roar, raised by women who worked, bled, and won against impossible odds. So pour it this Fourth of July. Taste the fury of seamstresses, maids, and outcasts who reshaped a nation. Their fight burns on.

Suffragette Punch

Description: A zesty, citrusy drink served at suffrage rallies in the Mid-Atlantic, symbolizing the vibrant energy of the women’s voting rights movement.

Yields: 8 servings (about 6 cups)

Prep Time: 10 minutes

Cook Time: 5 minutes (for simple syrup)

Ingredients:

- 1 cup lemon juice (from about 6 lemons)

- 1 cup orange juice (from about 4 oranges)

- 1 cup simple syrup (1 cup sugar + 1 cup water, heated until dissolved, then cooled)

- 4 cups cold water

- 1 cup club soda (optional, for fizz)

- Lemon and orange slices, for garnish

- Fresh mint leaves, for garnish

Instructions:

1. Prepare simple syrup: In a small saucepan, heat 1 cup sugar and 1 cup water over medium heat, stirring until sugar dissolves. Cool completely.

2. In a large pitcher or punch bowl, combine lemon juice, orange juice, simple syrup, and cold water. Stir well.

3. Just before serving, add club soda (if using).

4. Serve over ice, garnished with lemon slices, orange slices, and mint leaves.

Tips:

For an adult version, add ½ cup gin or vodka to the pitcher.

Use purple and white edible flowers (like violets) to nod to suffrage colors.

The United Mine Workers of America, formed in 1890, rallied in southern West Virginia, their fight erupting in 1921 at the Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest armed labor uprising in U.S. history. Over 10,000 miners, many World War I veterans bearing scars from foreign trenches, clashed with company thugs, corrupt sheriffs, and U.S. troops. The hills roared with gunfire, dynamite blasts, and cries for dignity, safety, and the right to organize. Mother Jones, an Irish-born firebrand branded “the most dangerous woman in America” by coal bosses, trudged through muddy hollers, her voice hoarse from rallying miners, wives, and children in secret meetings under the shadow of gunfire. She stood fearless, her gray hair wild in the wind, urging them to pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living, her words a torch in the coal-soaked dark igniting hearts worn raw by exploitation.

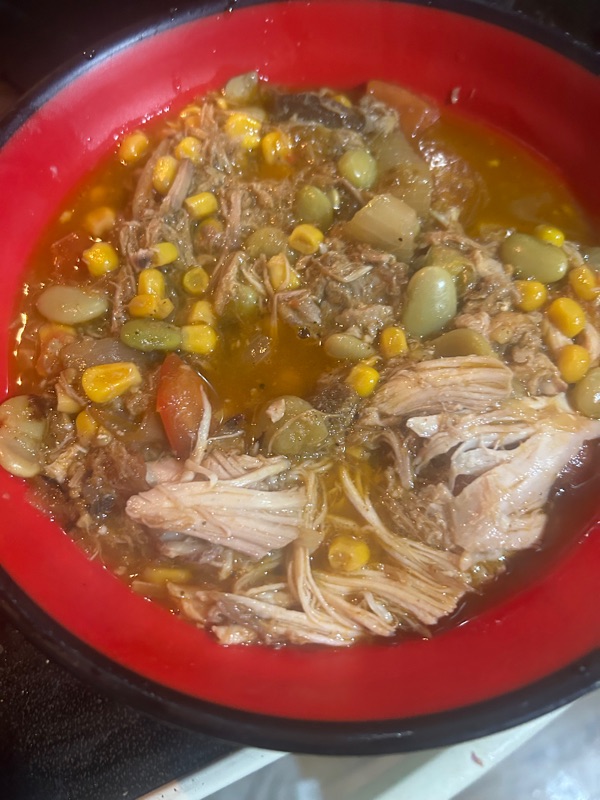

The fuse for Blair Mountain was the 1921 murder of Sid Hatfield, a pro-union sheriff gunned down by Baldwin-Felts agents on Welch courthouse steps in broad daylight. Hatfield, a legend since the 1920 Matewan Massacre where he stood down company goons, sparked fury with his death. Miners, tying red bandanas around their necks, a defiant flash that birthed the term redneck, gathered by the thousands, rifles gripped in calloused hands. Behind the lines, women, the backbone of the struggle, stirred Brunswick Stew, a dish born in Virginia or Georgia, now rooted in Appalachian survival. They boiled squirrel snared in the woods, rabbits trapped by the creek, or chickens from scrappy yards, mixed with tomatoes, corn, and lima beans scratched from rocky gardens. The stew stretched meager scraps to feed crowds, its steam rising from campfires in battered tin pots.

In miners’ camps, women, their hands calloused from washing, gardening, or mending, ladled stew into dented bowls after backbreaking days hauling water or scrubbing floors. Children, faces smudged with dirt, ran buckets of it to fighters on the ridges, dodging bullets to deliver warmth. Every spoonful was a pact, binding families against the coal barons’ stranglehold. The stew was not just food. It was rebellion, a refusal to starve or kneel. Miners faced machine guns, aerial bombings, and federal troops, their bellies warmed by stew that carried the taste of home, hearth, and unquenched hope. Though the U.S. Army crushed the uprising, Blair Mountain’s legacy endured, forcing the nation to face labor’s plight and paving the way for New Deal reforms in the 1930s.

Today, Brunswick Stew simmers in Appalachian kitchens, its ingredients modernized—chicken for squirrel, canned corn for fresh—but its soul fierce. At union picnics, church suppers, and protest rallies, it feeds the fight against wage theft, unsafe mines, and corporate greed. So cook it this Fourth of July. Taste the fury of miners, wives, and children who defied an empire with every steaming bowl. Their struggle still burns.

Brunswick Stew

- Description: A hearty Appalachian stew of game and vegetables, shared in miners’ camps during the Blair Mountain labor uprising, symbolizing solidarity.

- Yields: 6–8 servings

- Prep Time: 15 minutes

- Cook Time: 1–2 hours

Ingredients:

- 1 lb boneless chicken, cut into chunks

- ½ lb pork shoulder, cut into chunks

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- 2 cups diced tomatoes (fresh or canned)

- 1 cup corn kernels (fresh, frozen, or canned)

- 1 cup lima beans (fresh, frozen, or canned)

- 2 cups chicken broth

- ¼ cup barbecue sauce

- 1 tbsp Worcestershire sauce

- Salt and pepper, to taste

Instructions:

- In a large pot over medium heat, sauté onion until softened, about 5 minutes.

- Add chicken and pork, cooking until browned, about 8 minutes.

- Stir in tomatoes, corn, lima beans, chicken broth, barbecue sauce, Worcestershire sauce, salt, and pepper.

- Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low and simmer for 1–2 hours, stirring occasionally, until meat is tender and flavors meld.

- Serve hot with cornbread.

Southwest: Fajitas: Sizzling in the Shadows

In the sun-scorched ranches of South Texas, fajitas were born from the sweat and defiance of Mexican American vaqueros. In the 1930s, these cowboys, paid not in cash but in tough skirt steak castoffs, turned scraps into survival. They marinated the fibrous meat in tart lime and garlic, grilled it over crackling mesquite fires, and wrapped it in warm, hand-pressed tortillas. The smoky, sizzling result was bold, a working-class meal forged in hardship, shared with pride under starry borderland skies by families who refused to break under exploitation’s weight.

The story of fajitas is steeped in labor and resistance. From 1942 to 1964, the Bracero Program dragged millions of Mexican workers to U.S. fields, orchards, and railroads, promising fair wages but delivering misery. Braceros, housed in squalid shacks with leaking roofs and no heat, endured 12-hour days picking citrus under blistering sun, their wages stolen or docked for minor infractions. Pesticides burned their skin; bosses ignored their pleas for water or rest. Yet, in those desolate camps, they grilled fajitas over makeshift fires, the sizzle of meat a quiet rebellion against dehumanization. Women, often erased from history, cooked for families and workers, their hands calloused from picking fruit or scrubbing pots, weaving culture into every bite, their kitchens a refuge against oppression.

In 1954, the U.S. unleashed Operation Wetback, a brutal deportation campaign that tore over a million people from their homes. Mexican Americans, many born on U.S. soil, were rounded up alongside immigrants, their lives shattered under the guise of economic protection. Agents raided homes at dawn, splitting families and terrorizing communities. Borderlands became militarized wastelands, with checkpoints and fear choking daily life. Through this violence, fajitas endured in backyards and churches, each grill lit a refusal to vanish. The smoky aroma of carne asada carried memory and defiance, a stubborn claim: We belong here.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the Chicano Movement erupted across the Southwest. Mexican American youth demanded bilingual education, voting rights, and cultural pride. Kitchens became hubs of resistance, with fajitas fueling marches and meetings. César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, co-founders of the United Farm Workers, led farmworkers toiling in California’s Central Valley. Chávez fasted for weeks, his body frail but spirit iron, protesting pesticide poisoning and starvation wages, sparking grape boycotts that rattled agribusiness. Huerta, fierce and unyielding, championed women laborers—pickers, packers, mothers—whose backs bent under exploitation, their voices silenced by bosses and unions alike. Her cry, ¡Sí, se puede!, rang from Texas to Delano, a call to dignity that echoed in every tortilla wrapped around sizzling meat. Fajitas, shared at union gatherings, became a symbol of their fight, each bite fueling a people unbroken.

Fajitas are a legacy of borderland grit. From vaquero ingenuity to chain restaurant menus, their journey mirrors Mexican American resilience. Today, as deportations, border walls, and anti-immigrant policies persist, fajitas sizzle at community cookouts and protests, a testament to enduring struggle. So grill them this Fourth of July. Taste the fury of vaqueros, braceros, and farmworkers who turned scraps into defiance, their spirit unbowed.

Fajitas

- Description: Born from South Texas vaqueros’ ingenuity, fajitas use marinated skirt steak to celebrate Mexican American resilience amid immigration struggles.

- Yields: 4 servings (8 fajitas)

- Prep Time: 15 minutes (plus 30 minutes marinating)

- Cook Time: 15 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1 lb skirt steak

- 1 red bell pepper, sliced

- 1 green bell pepper, sliced

- 1 medium onion, sliced

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 2 tbsp lime juice (from about 1 lime)

- 1 tsp chili powder

- 1 tsp ground cumin

- Salt and pepper, to taste

- 8 flour tortillas, warmed

Instructions:

- In a bowl, combine olive oil, lime juice, chili powder, cumin, salt, and pepper. Add steak, coat well, and marinate for 30 minutes.

- Heat a large skillet or grill pan over high heat. Grill or sear steak for 3–4 minutes per side for medium-rare. Remove and let rest 5 minutes, then slice thinly against the grain.

- In the same skillet, sauté bell peppers and onion until soft, about 5–7 minutes.

- Serve sliced steak and vegetables in warm tortillas with salsa, guacamole, or sour cream.

Tips:

- Substitute chicken or portobello mushrooms for vegetarian fajitas.

- Warm tortillas in a dry skillet or microwave for softness.

Deep South: Collard Greens: Soul of the Nation

To truly grasp the profound significance of collard greens in the Civil Rights Movement, one must delve into a deeper, layered narrative—one of survival, rebellion, and working-class defiance, stretching from the transatlantic slave trade to the heart of 20th-century protest.

Collard greens, botanically known as Brassica oleracea acephala, may have originated in the Mediterranean, but their true legacy in the United States was forged in the soil of Southern plantations. When enslaved Africans were forcibly brought to the Americas, they carried with them agricultural wisdom, culinary memory, and a determined will to survive. Denied access to full rations and proper nutrition, enslaved people cultivated small garden plots where they grew hardy, nutrient-rich crops like collard greens. These greens, cooked slowly with bits of smoked meat or fatback, became a critical supplement to a meager diet based on cornmeal and pork scraps. The resulting broth—pot likker—was precious, sopped up with cornbread and revered for its vitamins and minerals.

This wasn’t just cooking. It was resistance.

From scraps, enslaved families forged sustenance and culture. From deprivation, they created a cuisine—what we now call soul food. Collard greens were a culinary act of rebellion against a system designed to starve both body and spirit. They embodied ingenuity, community, and care: a quiet but enduring refusal to be broken.

After emancipation, collard greens remained on Southern tables. Freedmen and women planted them in backyard gardens, in tenant plots, and around sharecropper cabins. During Jim Crow, they became comfort food in a world still defined by segregation and inequality. They anchored Sunday dinners and church gatherings, reinforcing kinship ties and preserving ancestral memory.

And then came 1954.

In that year, Brown v. Board of Education lit a spark that would ignite a decade of revolution. The Supreme Court's ruling declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional, challenging the very foundation of Jim Crow. It was the first legal blow in what would become a mass working-class rebellion led by African Americans—domestics, barbers, preachers, teachers, and factory workers—who demanded not just integration, but dignity.

In 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus. What followed was a 381-day boycott, led by everyday Black citizens, who carpooled, walked for miles, and organized. During those long months, church kitchens and family homes kept the movement alive with meals—many of them featuring collard greens. They fed bodies that marched and minds that strategized, transforming food into fuel for revolution.

The movement spread: from the sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, to the Freedom Rides through the Deep South, to Birmingham and its jailhouse letters. At each stage, this was a working-class uprising—a grassroots mobilization where hospitality and resistance walked hand in hand. Homes became sanctuaries, churches became planning rooms, and meals became moments of rest and resistance.

By 1965, the crescendo was Selma. After the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson and the violent suppression of peaceful protestors on Bloody Sunday, the eyes of the nation turned to the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Marchers, many of them teachers, maids, steelworkers, and farmers, faced tear gas and clubs with nothing but courage and conviction. And behind them stood the kitchens of the movement—feeding, tending, caring.

It was here, in the long shadow of oppression, that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. helped lead the march from Selma to Montgomery, walking shoulder to shoulder with laborers, students, and elders alike. King's vision of justice was never limited to racial equality alone—it was deeply entwined with economic dignity. He understood that civil rights without bread on the table was a hollow promise. That’s why he preached from pulpits and porches, why he sat at dinner tables with sharecroppers and sanitation workers, and why he invoked the sacred act of breaking bread as a symbol of shared humanity and struggle.

Collard greens simmered in those kitchens. They were passed across folding tables in fellowship halls and packed into tinfoil for weary marchers. They were comfort and continuity, linking the generations who had endured slavery, survived Jim Crow, and now stood demanding the right to vote. Around pots of greens, stories were shared, songs were sung, and fear was met with solidarity.

Thus, the humble collard green—once deemed unworthy by those in power—became a leafy banner of resistance. It symbolized nourishment not just for the body, but for the soul. It was the food of the enslaved, the freed, the segregated, and the marching. A Southern staple, yes—but more than that, a revolutionary emblem rooted in struggle.

From field to fork, from bondage to ballot box, collard greens carried the people forward.

Collard Greens

- Description: A soul food cornerstone, simmered with bacon, sustaining Civil Rights marchers in 1965 Selma with nourishment and cultural resilience.

- Yields: 4–6 servings

- Prep Time: 15 minutes

- Cook Time: 1–1.5 hours

Ingredients:

- 1 lb collard greens, stems removed, leaves chopped

- ½ lb bacon, chopped

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- 2 garlic cloves, minced

- 2 cups chicken broth

- 1 tbsp apple cider vinegar

- 1 tsp granulated sugar

- Salt and pepper, to taste

Instructions:

- In a large pot over medium heat, cook bacon until crisp, about 8 minutes. Remove bacon and set aside, leaving fat in the pot.

- Add onion and garlic to bacon fat; sauté until softened, about 5 minutes.

- Add collard greens, chicken broth, apple cider vinegar, sugar, salt, and pepper. Stir to combine.

- Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low and simmer for 1–1.5 hours, stirring occasionally, until greens are tender.

- Stir in reserved bacon and serve hot, with pot likker and cornbread.

Tips:

- Use smoked turkey or ham hocks instead of bacon for variation.

- Save pot likker (broth) for dipping cornbread or as a nutrient-rich base for soups.

Great Lakes: Chicago Style Hot Dog: All The Way

The origins of the Chicago dog trace back to late 19th and early 20th century waves of German, Polish, and Eastern European immigrants, who brought with them sausage-making traditions that thrived in the city’s crowded neighborhoods. Chicago’s streets quickly filled with pushcarts selling hot dogs—cheap, fast, flavorful food made for people who worked with their hands, who couldn’t spare time or money for white-tablecloth establishments. During the Great Depression, vendors began loading their franks with vegetables to stretch the meal further for hungry workers. Thus was born the “dragged through the garden” style: a hot dog dressed with all the fixings—crisp, acidic, spicy, sweet, and sharp. A working-class salad in a bun.

This street-level culinary innovation mirrored the larger spirit of survival and dignity that coursed through the city’s blue-collar communities. For decades, Chicago was a hub of labor organizing, of tenement protests and union halls, of meatpacking resistance and neighborhood mutual aid. The Chicago dog, humble and unpretentious, was part of that everyday rebellion—an edible symbol of joy and self-respect amid struggle.

By the 1950s and ’60s, amid civil rights marches and feminist organizing, a quieter but equally urgent fight was unfolding in the margins: the push for visibility, autonomy, and respect for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disabled children were often institutionalized, segregated, or denied even the most basic opportunities for education and social interaction. Yet working-class families—often with few resources but abundant determination—were among the first to push back, refusing to accept invisibility as the price of disability.

Among those families was the Kennedy clan. Eunice Kennedy Shriver, moved by her sister Rosemary’s experience, began hosting summer camps in her backyard, where children with intellectual disabilities could swim, play, and compete. She believed what many parents and advocates already knew: that sports could be a powerful vehicle for inclusion, joy, and visibility. It was not charity—it was justice.

That belief culminated in the summer of 1968, when Soldier Field in Chicago hosted the first International Special Olympics Games. Co-sponsored by the Kennedy Foundation and the Chicago Park District, the games welcomed over 1,000 athletes from across the U.S. and Canada. For many participants—children and teens who had spent their lives on the sidelines—this was the first moment they were publicly celebrated for their abilities rather than defined by their disabilities.

The day was electric. As athletes sprinted and leapt under the July sun, the smell of grilled hot dogs wafted through the crowd. Vendors outside the stadium served them hot and loaded, the same way they had been for steelworkers, janitors, and bus drivers for decades. On that day, they were served to athletes and families from every background—Black, white, disabled, working-class, poor, and proud. In that moment, the Chicago dog became more than sustenance—it became a shared meal of recognition.

In a city fractured by racial segregation and economic inequality, the Special Olympics created an unlikely communal space—where children with disabilities, especially Black and brown children often marginalized twice over, could find belonging. It also galvanized deeper organizing.

Inspired by the visibility fostered at Soldier Field, Chicago became a pivotal site in the growing disability rights movement. In 1977, disability activists across the country staged sit-ins demanding enforcement of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which prohibited discrimination in federally funded programs. Though Chicago did not host a sit-in of its own, the energy reverberated through the city, and momentum built.

By the early 1980s, the streets of Chicago were again alive with protest—this time, for transit justice. Activists in wheelchairs blocked CTA buses that lacked lifts, demanding full accessibility. They staged “crawl-ons,” dragged themselves up bus steps, and refused to be ignored. Their bodies became banners. Their chants echoed through the city. And always, nearby, street vendors grilled hot dogs—served on street corners, at rallies, at meetings in church basements. These protests felt like block parties and strikes at once—where solidarity was measured in both slogans and shared snacks.

In 1980, Access Living was founded in Chicago, becoming one of the nation’s leading independent living advocacy organizations. What began as summer joy on a sports field grew into year-round pressure on policymakers, institutions, and transit boards. Disabled Chicagoans—many of them working-class, Black, brown, and overlooked—were demanding more than access. They were demanding equity, pride, and presence.

Today, Chicago-style hot dogs are still served at Special Olympics fundraisers and disability pride events. The toppings are the same, but the meaning has grown. The Chicago dog, exuberant and layered, remains a democratic food—made for the streets, for the people, and for anyone with the courage to demand a seat at the table.

Because great food and great change often come from the same sidewalks.

And in Chicago, sometimes they come in a poppy seed bun, dragged through the garden, and handed to someone who’s finally being seen.

Chicago-Style Hot Dog

Description: A vibrant, vegetable-loaded hot dog reflecting Chicago’s working-class and immigrant roots, tied to the Special Olympics and disability rights.

Yields: 4 servings

Prep Time: 10 minutes

Cook Time: 10 minutes

Ingredients:

- 4 all-beef hot dogs (preferably Vienna Beef)

- 4 poppy seed hot dog buns

- Yellow mustard, to taste

- Neon green relish, to taste

- ½ cup chopped white onion

- 4 tomato wedges

- 4 dill pickle spears

- 8 sport peppers

- Celery salt, to taste

Instructions:

- Grill or boil hot dogs until heated through, about 5–7 minutes.

- Steam or microwave poppy seed buns until soft, about 20–30 seconds.

- Place hot dogs in buns. Top with mustard, relish, onion, tomato wedges, pickle spears, sport peppers, and a dash of celery salt.

- Serve immediately with fries.

Tips:

- Never use ketchup, per Chicago tradition.

- For homemade poppy seed buns, see below for a detailed recipe.

Homemade Poppy Seed Hot Dog Buns

Yields: 8–10 buns

Prep Time: 40 minutes (plus 1.5–2 hours rising)

Cook Time: 18–25 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1 cup warm milk (110–120°F / 43–49°C)

- 2 tsp instant yeast (or active dry yeast)

- 2 tbsp granulated sugar

- 2 ½ cups all-purpose flour (or bread flour)

- 1 tsp kosher salt

- 1 large egg

- 3 tbsp unsalted butter, melted and cooled

- 1 large egg white (or whole egg, for egg wash)

- 2 tsp cold water

- 3 tbsp poppy seeds

Instructions:

- If using active dry yeast, combine warm milk, 1 tsp sugar, and yeast in a bowl; let sit 5–10 minutes until foamy. (Instant yeast can be mixed directly with dry ingredients.)

- In a large bowl or stand mixer, combine 2 ¼ cups flour, remaining sugar, and salt. Add yeast mixture (or instant yeast), egg, and melted butter. Mix until a shaggy dough forms.

- Knead on a floured surface (or with dough hook) for 5–7 minutes, adding remaining ¼ cup flour as needed, until smooth and elastic.

- Place dough in a greased bowl, cover with plastic wrap, and let rise in a warm place for 60–90 minutes until doubled.

- Deflate dough and divide into 8–10 equal pieces (70–80g each). Shape into 5–6 inch logs, pinching seams. Place seam-side down on a parchment-lined baking sheet.

- Cover loosely and let rise for 30–45 minutes until puffy.

- Preheat oven to 350°F (175°C). Whisk egg white with water for egg wash. Brush buns and sprinkle with poppy seeds.

- Bake for 18–25 minutes until golden. Cool on a wire rack..

West Coast: Avocado Eggs Benedict: Brunch of Belonging

Though the dish’s exact origin is elusive, its evolution is unmistakably Californian. Classic Eggs Benedict—rich with poached eggs and velvety hollandaise—traveled west and collided with California’s agricultural abundance and health-conscious flair. In that fertile ground, avocado became more than a garnish; it became a statement. A symbol of freshness, reinvention, and defiant self-definition. And nowhere did that reinvention feel more at home than in the Castro.

But to understand the political weight of brunch in queer history, we have to go back—not just to 1969’s Stonewall uprising in New York, but to August 1966, in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. There, in the florescent-lit booths of Compton’s Cafeteria, a group of trans women, drag queens, and queer sex workers pushed back—literally—against the violent harassment of police. That night, coffee cups were thrown, sugar shakers smashed, and heels hurled through glass. It was one of the first known organized acts of queer resistance in U.S. history. And it happened over late-night meals, in a working-class cafeteria where the marginalized gathered for warmth, safety, and belonging.

Compton’s wasn’t just a place to eat—it was a place to organize. For many, it was the only spot in the city where they could sit down, be seen, and strategize without being immediately kicked out. The riot didn’t come out of nowhere—it came out of accumulated dignity, brewed over coffee and hash browns. And it sparked a movement that would eventually ripple through the Castro and across the nation.

By the early 1970s, as queer people were pushed out of other neighborhoods by gentrification and police pressure, the Castro became a sanctuary. Its transformation wasn’t just about geography—it was about survival, solidarity, and self-determination. And brunch became one of the rituals that held it all together.

In a time when queer bars were regularly raided and queer people were fired or evicted for simply existing, Sunday morning brunch offered a different kind of visibility. Drag brunches, in particular, became both performance and protest—joyful, defiant, and gloriously ungovernable. They were spaces where gender norms were dismantled with rhinestones and hollandaise. Where laughter was political, and mimosas were poured between rounds of fundraising and mutual aid planning.

Queer cafés and diners doubled as informal command centers—where organizing for housing, HIV awareness, legal protections, and labor solidarity took place in full daylight. For queer people of color, trans folks, and sex workers—those too often sidelined even within the gay rights movement—brunch was a rare equalizer. A place to regroup. To strategize. To breathe.

At the heart of this movement stood Harvey Milk, a camera shop owner turned activist whose charisma and commitment helped galvanize a growing chorus of queer voices. After arriving in the Castro in 1972, Milk quickly became a fixture—not just as a politician-in-the-making, but as a neighbor who listened, joked, and shared meals with everyone from street kids to union leaders. He understood that the struggle for gay rights was inseparable from the broader struggles of the working poor, seniors, people of color, and laborers. He fought for rent control, public transportation, and union jobs just as fiercely as he fought for queer liberation.

Milk often held court in the same cafés that served up steaming plates of Avocado Eggs Benedict to drag queens, activists, and families alike. When he rallied the Castro against Proposition 6—the Briggs Initiative that sought to ban gay and lesbian teachers—he did so not from a distant podium, but from brunch tables, shop counters, and street corners. His politics weren’t just intersectional—they were deeply rooted in local, working-class relationships.

Then, in November 1978, everything changed. Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone were assassinated in their offices at City Hall. Grief swept through the Castro like fog rolling in from the bay. That night, tens of thousands of mourners carried candles from the Castro to City Hall in a silent procession. And the next morning, in the diners and cafés where so many had organized, the mood was heavy. Plates of Eggs Benedict were served in silence, tears mingling with coffee, and one question lingered in the air: What now?

The answer came slowly—and with fire.

In the 1980s, as the AIDS crisis decimated the community, the brunch tables that once served as sites of celebration became command centers of grief and rage. Groups like ACT UP and Queer Nation were born between bites of toast and slams of coffee mugs. Organizers coordinated die-ins, health clinics, and legal defense funds over shared meals. Trans Latina activists, often left out of mainstream LGBTQ organizing, used brunch spaces to build networks of care and protest, advocating for survival in a system stacked against them.

Still today, the Avocado Eggs Benedict remains a staple on Castro menus. At Harvey’s, a diner named in Milk’s honor, it’s served beneath black-and-white photos of marches, vigils, and drag queens in full regalia. During Pride Month, the dish appears at brunch buffets across the city, flanked by rainbow flags and protest flyers. Its creamy hollandaise and rich yolks are more than indulgence—they’re remembrance. They’re rebellion.

Because brunch in the Castro has never just been about eggs and avocado. It has been about transformation—of pain into power, of marginalization into movement. A space where the marginalized became organizers, and where joy itself was political.

Each forkful is a quiet memorial. A celebration of chosen family. A declaration that justice is still being served—and yes, it comes with hollandaise.

Avocado Eggs Benedict

- Description: A Californian twist on a classic, this dish with creamy avocado and hollandaise reflects the Castro’s vibrant LGBT brunch culture and resistance.

- Yields: 4 servings (8 halves)

- Prep Time: 20 minutes

- Cook Time: 15 minutes

Ingredients:

- 4 English muffins, split and toasted

- 8 large eggs

- 1 ripe avocado, sliced

- 8 slices bacon

- 2 tbsp unsalted butter

- Salt and pepper, to taste

- Hollandaise Sauce:

- 3 egg yolks

- 1 tbsp lemon juice

- 1 tsp Dijon mustard

- ¼ tsp salt

- Pinch of cayenne pepper

- ½ cup unsalted butter, melted and hot

Instructions:

- Hollandaise Sauce: In a blender, combine egg yolks, lemon juice, mustard, salt, and cayenne; blend for 5 seconds. With blender running, slowly stream in hot melted butter until emulsified. Set aside, keeping warm.

- Cook bacon until crisp, about 8 minutes. Drain on paper towels.

- Poach eggs: Bring a pot of water to a simmer, add a splash of vinegar, and gently poach eggs for 3–4 minutes until whites are set but yolks are runny. Remove with a slotted spoon.

- Toast English muffins and spread lightly with butter.

- Assemble: On each muffin half, layer bacon, avocado slices, a poached egg, and a spoonful of hollandaise. Season with salt and pepper.

- Serve immediately.

Tips:

- Use a double boiler for hollandaise if no blender is available; whisk constantly to avoid curdling.

- Substitute Canadian bacon or smoked salmon for traditional variations.

Hawai‘i: Poke Bowls: Ahi and Apologies

The fragrant aroma of shoyu-marinated ‘ahi, toasted sesame oil, and freshly grated ginger wafted through the humid air—mingling with the sounds of oli (chants), the rhythmic beat of pahu drums, and the hushed murmurs of families gathered beneath the banyan trees outside ʻIolani Palace in 1993. For those assembled, the poke bowl in their hands was more than just a meal—it was a declaration. It was nourishment not only for the body but for a collective memory: a living link between the past and the promise of what could still be reclaimed.

On the centennial of the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Native Hawaiians returned en masse to the gates of the palace—the last royal residence of Queen Liliʻuokalani. They weren’t there simply to protest. They came to occupy, to reclaim, and to remind the world of what had been stolen: not just a monarchy, but a sovereign nation, a language, a worldview. And they brought food—their food—with them. Poke, with its roots in the pre-contact tradition of fishermen salting and seasoning reef fish with seaweed and roasted kukui nut, was passed from hand to hand, a quiet act of cultural defiance. It was not the poke of chain restaurants and Instagram trends. It was the real thing: raw, resilient, and deeply tied to ʻāina (land) and kai (sea).

Unlike Indigenous communities in the continental United States, whose tribal status is (at least nominally) recognized by the federal government, Native Hawaiians occupy a unique and deeply unsettled legal space. While Native American and Alaska Native tribes possess government-to-government relationships with Washington, Kanaka Maoli remain in legal limbo. The reason? They were not tribal subjects. They were citizens of an internationally recognized nation-state—a nation that was overthrown with the aid of U.S. Marines and annexed without consent.

Before 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom had its own constitution, legislature, land system, and foreign embassies. It signed treaties with nations like Britain, France, and the United States. This was not the annexation of a tribal territory—it was the overthrow of a sovereign state. And for over a century since, the U.S. has refused to fully acknowledge that distinction. Efforts like the Akaka Bill, which sought to grant federal recognition to a Native Hawaiian governing entity, were met with opposition and failed repeatedly—not because Hawaiians lacked a political identity, but precisely because their identity did not fit into existing U.S. frameworks.

Instead, Hawaiians were asked to shrink themselves—into checkboxes, into census categories, into a version of indigeneity that erased their history as a nation. This erasure had consequences. Native Hawaiians today are disproportionately represented among the houseless, incarcerated, and chronically ill in their own homeland. Real estate speculation and tourism have driven many off ancestral lands. Hawaiian culture—once criminalized, then commodified—struggles to survive in the place of its birth.

But culture never disappeared. It adapted. It simmered in backyard imu pits, was sung in protest mele, taught in immersion schools, danced in hālau, and whispered through limu-gathering expeditions on the shore. By the 1970s, a wave of cultural revival—the Hawaiian Renaissance—began reshaping the islands. What started as a resurgence of language, music, and hula soon evolved into direct political action. From the occupation of Kahoʻolawe to legal battles for water rights, a new generation began to connect cultural practice with sovereignty.

The 1993 occupation of ʻIolani Palace was the culmination of that awakening. Thousands arrived—not just activists, but kūpuna (elders), keiki (children), teachers, musicians, and fishermen. Amid chants and flag raisings, people huddled under tarps and pop-up tents, where food was prepared communally. And always, there was poke.

Each bowl served was a reminder: Hawaiians never stopped being Hawaiian. Even when their language was banned in schools, even when their queen was imprisoned in the palace just steps away, even when every legal channel failed to deliver justice—they kept fishing, gathering, seasoning, sharing. Every bite carried generations of skill, memory, and resistance. The poke was caught with inherited knowledge, seasoned by hand, and offered freely. It was more than sustenance—it was sovereignty you could taste.

The U.S. government’s eventual response—the 1993 Apology Resolution, signed by President Clinton—acknowledged the illegality of the overthrow and expressed "regret," but offered no restitution, no land, no recognition. Yet something had shifted. For many young Kanaka Maoli, the occupation was their first political memory. They saw the palace not as a relic, but as a living site of struggle. They saw their culture not as a thing of the past, but as a weapon for the future.

In the decades since, that spirit has only deepened. From Mauna Kea to Hūnānāniho, land protectors continue to draw from the same cultural well—bringing laulau, lomi salmon, and poke to the frontlines. Food is not secondary to the movement—it is the movement. It reminds everyone gathered that Hawaiian identity is not up for negotiation. It is lived, embodied, eaten, and shared.

Meanwhile, poke bowls have spread across the globe, often stripped of their cultural context and turned into fast-casual novelties. But in Hawaiʻi, for those who know, a true bowl of poke still carries mana (spiritual power). It tells a story—of reef and resistance, of overthrows and occupations, of grief and gratitude.

Because sovereignty isn’t just about paperwork or politics. It’s about planting kalo, speaking ʻōlelo, preparing fish the way your tūtū kane did, and feeding your community with knowledge as much as nourishment. It’s about gathering at the foot of a palace with a bowl in your hands and knowing exactly who you are.

For my poke bowl, instead of ahi, I used canned tuna, changing up the recipe a little bit.

Canned Tuna Poke Bowl

Description: A quick, pantry-friendly version of traditional Hawaiian poke, reflecting Native Hawaiian resilience and sovereignty movements.

Yields: 1 serving

Prep Time: 15 minutes

Cook Time: 15–20 minutes (for rice)

Ingredients:

- 1 (5 oz) can tuna (in water or oil), drained and flaked

- 1 tbsp soy sauce (or tamari)

- 1 tsp toasted sesame oil

- ½ tsp rice vinegar

- ¼ tsp grated fresh ginger (optional)

- Pinch of red pepper flakes (optional)

- 1 green onion, thinly sliced

- 1 cup cooked white or brown rice

- ½ small cucumber, thinly sliced

- ¼ cup cooked edamame

- ¼ cup shredded carrots or sliced red cabbage

- ¼–½ avocado, sliced or diced

- Spicy Mayonnaise:

- 2 tbsp mayonnaise

- 1 tsp sriracha

- ¼ tsp lime juice

- Optional Toppings: Pickled ginger, nori strips, sesame seeds

Instructions:

- Cook rice according to package instructions; optionally season with 1 tsp rice vinegar and a pinch of salt.

- In a small bowl, mix tuna with soy sauce, sesame oil, rice vinegar, ginger, red pepper flakes, and half the green onion.

- In a small bowl, whisk mayonnaise, sriracha, and lime juice for spicy mayo.

- In a serving bowl, layer rice, then arrange tuna, cucumber, edamame, carrots, and avocado.

- Drizzle with spicy mayo and garnish with remaining green onion, pickled ginger, nori strips, and sesame seeds.

- Serve immediately.

Tips:

- Use fresh sushi-grade tuna for a traditional poke if available.

- Customize with other toppings like seaweed salad or tobiko.

Comments

Post a Comment