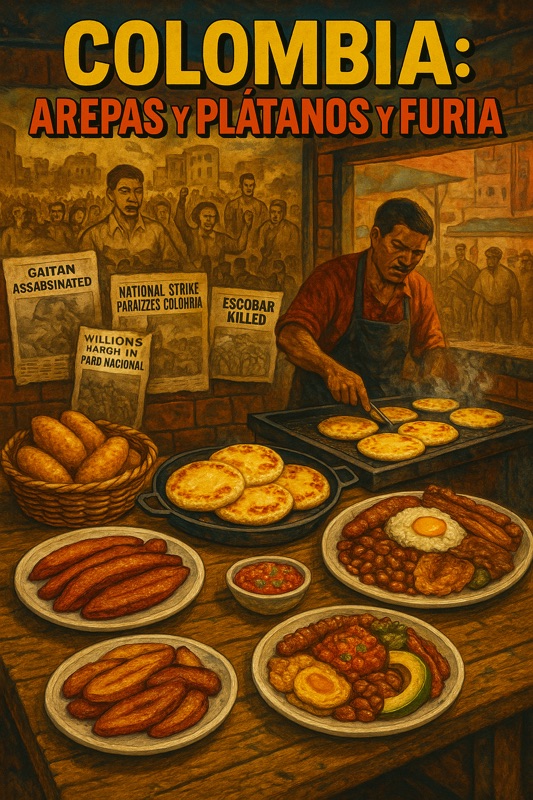

Colombia: Arepas y Plátanos y Furia

Colombia: Arepas y Plátanos y Furia

Colombia was the first nation in South America to declare its independence. It’s a land where South America meets Central America, where the soaring Andes converge with the lush Amazon, and where both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts bustle with beauty and life. Simón Bolívar, the founding father of “Gran Colombia,” looms large in the nation’s narrative, a hero whose legacy as a freedom fighter is as important to Colombians as that of George Washington in the United States.

Yet, beneath the grandeur of independence and the celebrations of national heroism, the real Colombia is found on the streets, in its markets, and in its kitchens. Between state repression, cartel violence, paramilitary terror, and capitalist exploitation, Colombia’s working-class food is more than just cuisine; it has been the rations for the working-class war that has continued throughout the country’s history.

Today we look at how arepas con queso, savory discs of white corn flour and cheese, helped provide the working class with a sense of normalcy as La Violencia raged around them. We discuss how a traditional breakfast platter from Medellín powered the city’s working people as they were in the crosshairs of drug lords, the Colombian government, the DEA, and right-wing paramilitary groups during the Narco Wars. Carimañolas, Afro-Colombian yuca fritters, became a rallying cry for labor rights during the 1977 National Civic Strike, while tajadas de plátano carried the heritage of displaced Afro-Colombian communities fleeing paramilitary violence in the 1990s. Finally, patacones con hogao, twice-fried plantains, fueled protesters during the 2021 Paro Nacional, a modern stand against inequality.

Make sure you come hungry, for knowledge and for something fried, as we dive in.

Arepas con Queso: Griddled in the Ashes

Few foods are more associated with Colombia than arepas con queso. Arepas, savory (and often sweet) griddled cakes made with white corn flour, had been made in some form centuries prior to Spanish arrival. The Spanish brought cheese with them, adding a nice gooey, cheesy middle to the classic discs of corn. Today there are over 75 varieties that can be found, served all over the country of Colombia. They are often a breakfast staple, served with coffee. Because they are such a staple and are so easy to make, they are often a comfort food during difficult times, and few times were more difficult in Colombia’s history than the violence that began in 1948.

For most of Colombia’s political history, power had been swapped back and forth between the Conservative Party, tied to the rural landholding elite and Catholic Church, and the Liberal Party, more closely associated with secular urban merchants, artisans, and skilled laborers. The primary means this power was exchanged was at the ballot box, but it wasn’t always quite so peaceful. Both the Liberal Party and Conservative Party in Colombia maintained armed civilian irregular units, chulavitas, and frequently took power through violent means.

During the 1930s, during one of the periods of Liberal rule, the Liberal Party became much more open to state intervention to help the working class in Colombia, very much like with progressivism or the New Deal in the United States. One particular Liberal leader, Bogotá’s mayor Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, espoused a series of policy proposals called the Gaitanista Program, or liberal socialism.

These policies included a set work day, nationalization of social programs, increased access to education, progressive taxation, land reform, among other left-wing priorities. This didn’t sit well with the more orthodox “Small Government” Liberals, Conservatives who viewed him as a radical, Communists who viewed him as a reformist espousing populist rhetoric for votes, and it especially didn’t sit well with the American United Fruit Company, who owned vast swathes of land for banana plantations and would try to portray him to American leadership as a communist and panic that a revolution was on its way. Gaitán would actually briefly leave the Liberal Party due to disagreements and form his own party, the National Leftist Revolutionary Union. But his policies would become immensely popular with the masses, and the Liberal Party would let him back in. Under his mayoral term, the working class of Bogotá would begin to thrive, and a vibrant street food culture would emerge, with arepas con queso being served from stalls lining streets and in the middle of markets, hot and ready to go.

In 1946, the Liberal Party was so split they ran two candidates for president: Gaitán and the more moderate Gabriel Turbay. As a result, the Conservatives won, ending a decade-plus of Liberal rule. The Liberals would see the need to get behind the Gaitanista program, and Gaitán would become leader of the Liberal Party, with the expectation that he would run again in the 1948 elections and be the odds-on favorite to win.

It should be said that in April 1948, the Cold War was in its early stages. The Iron Curtain had just recently fallen across Eastern Europe, and the Pan-American Conference was being held in Bogotá, as the US government was eager to push an anti-communist line across the continent of South America, with US Secretary of State George Marshall providing a statement against communism that delegates from each of the Latin American states were expected to sign. The backdrop of the inevitable win of Gaitanismo created a large amount of unease. Conservatives had not gotten into government since 1930, with President Ospina being the first elected under the peaceful, civil system of convivencia, and they were eager to keep it.

On the afternoon of April 9, 1948, all was still in Bogotá. Arepas were sizzling on stalls in the street, their savory scents wafting through the air. Gaitán was having lunch with a supporter. As he was leaving, a lone gunman shot him several times as he fell to the ground, dead. The gunman was immediately pursued by an angry mob of onlookers, his face mutilated and torn apart beyond recognition. To this day it is not known who was responsible. A lone gunman with mental illness, the conservative government of President Ospina, the CIA, communists—it doesn’t matter. What matters is that Bogotá erupted into a rash of rioting that would become known as the Bogotazo.

Gaitán was an immensely popular figure in Bogotá. Local radio stations immediately started blaming the government for his assassination, telling people to take to the streets and broadcasting instructions on how to create Molotov cocktails. People started burning hardware stores, looting, flipping over arepa carts, and storming government buildings. Liberal leaders asked people to stop the violence, but it did little good.

The riots lasted 10 hours, and it is thought between 3,000 and 5,000 people died. The Liberals and Conservative government of President Ospina initially started working together to instill peace and root out communist agitators. However, the Liberals were quickly blamed for the uprising, with police arresting Liberal leaders around the country. The Liberals would begin using their majority in the legislature to impeach the president, and President Ospina would dissolve the Congress. With Bogotá in ruins, arepas cracked and leaking molten cheese on the streets, conservative landowners in the countryside were already mobilizing paramilitaries to seize land from Liberal and Communist peasants. Communist guerrillas, allied with the liberals, began activating in the countryside. It was clear the civility of the convivencia was over, giving way to La Violencia, a ten-year civil war that raged on the streets and in the countryside between Conservatives and Liberals.

The justification for this fighting was conspiratorial, with Conservative forces claiming the Liberals were part of a Judeo-Masonic conspiracy to destroy Christianity. The Liberals portrayed the Conservatives as ex-Nazis and Francisco Franco supporters who escaped Europe at the end of World War II. Both sides saw these paranoid delusions as justification to eliminate the other.

During this time, arepas con queso became a quiet symbol of resilience and comfort. Guerrilla fighters found them easy to make, corn flour and cheese easy to find, and a simple frying pan easy to carry. The working class, who bore the brunt of this violence, turned to making arepas when times were tough and supply lines were ruined. During the infighting, it is thought that 200,000 to 300,000 people were killed, playthings for warlords.

The period of La Violencia was resolved when moderate leaders from both parties came to an agreement in 1956, the establishment of The National Front, where Conservatives and Liberals would alternate control of the presidency and share cabinet positions. The paramilitary leaders who took part in the fighting would go on to found other paramilitaries, with La Violencia’s participants founding left-wing paramilitaries that would later become groups like FARC and right-wing paramilitaries that would become groups like AUC. Arepas con queso remained a staple and do to this day.

Arepas con Queso are one of my all-time favorite things to make. I make them for everything: breakfasts, festivals, parties. They are easy to make, and I know you’ll love them.

Arepas con Queso Recipe

Arepas are a staple in Colombia, often served for breakfast or as a side. These cheesy corn cakes are a true delight!

• Yields: 10–12 arepas

• Prep Time: 15 minutes

• Cook Time: 20–30 minutes

Ingredients

• 2 cups pre-cooked white cornmeal (masarepa)

• 2 teaspoons salt

• 2 teaspoons sugar (optional, but enhances flavor)

• 2 tablespoons unsalted butter, softened

• 2 cups (about 8 oz) shredded mozzarella cheese, divided (or a mix of mozzarella and queso fresco)

• ¼ cup whole milk (optional, for a richer taste)

• 2 ½ cups lukewarm water

• Nonstick cooking spray or a little oil for cooking

Instructions

1. Make the dough: In a large bowl, whisk together the masarepa, salt, and sugar.

2. Add the softened butter and 1 ½ cups of the shredded mozzarella cheese.

3. Slowly drizzle in the milk and lukewarm water as you knead the dough with your hands. Mix well until all ingredients are incorporated and you have a soft, cohesive dough. It might be a bit sticky at first but will firm up as it rests.

4. Rest the dough: Let the dough rest, uncovered, for about 5 minutes to allow the masarepa to absorb the liquid.

5. Shape the arepas: Divide the dough into 10–12 equal portions. Lightly wet your hands with cold water to prevent sticking.

6. Roll each portion into a ball. If you want a “cheese pull” in the center, press your thumb into the center of a dough ball to create an indentation. Fill with about a tablespoon of the remaining shredded mozzarella. Gently fold the dough over to enclose the cheese and re-roll into a ball.

7. Flatten each ball into a patty about ½ inch thick and 4–5 inches in diameter, smoothing the edges.

8. Cook the arepas: Heat a nonstick skillet, griddle (budare), or cast iron pan over medium heat. Lightly grease with cooking spray or a little oil.

9. Place the arepas on the hot surface and cook for about 4–7 minutes per side, or until golden brown with some charred spots and firm to the touch. The cheese inside should be melted.

10. Serve hot. Arepas are delicious on their own or can be split and filled with more cheese, hogao, or other fillings.

Carimañolas: Fried and Fired Up

Carimañolas are torpedo-shaped fritters made from fried yuca dough and stuffed with a meat filling. They are most commonly associated with the Caribbean and Pacific Coasts of Colombia, and the vibrant Afro-Colombian culture located there—the cuisine of those who descended from slaves who were brought in during the era of Spanish colonization. Carimañolas are a symbol of Afro-Colombians and have been spread throughout Colombia as they have.

One such time of migration was the 1970s. Economic opportunities had been drying up on the coasts, and Afro-Colombians began moving to larger cities, cities such as Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali. With them, they brought carimañolas, and street vendors began popping up selling these golden fritters in every city in Colombia.

Unfortunately, the economic situation in the cities was not much better. Afro-Colombians often found themselves with low wages and no benefits, lack of services, and with a rising cost of living. This wasn’t just an Afro-Colombian issue either. The urban working class was hurting in the 1970s.

The four major labor unions of the time had joined into one organization to strengthen their hand. This new National Trade Union Council would demand a 50% increase in wages in 1977, something the government rejected. The National Trade Union Council then called a strike of all their employees.

However, something unexpected happened. The skilled laborer union members weren’t the only ones who began striking. The urban poor also began striking. Largely Afro-Colombian, they joined the picket lines, many of the street vendors serving carimañolas to strikers as the major urban organs of Colombia ground to a halt. Trains stopped running, people walked home on deserted streets, and it quickly became a problem for the Liberal government.

The government responded quickly and violently. Thousands of protesters were detained in one day, and at least 500 injured by police. At least 18 people died. Despite all this, the strike continued, and strikers carried on, fueled by carimañolas in hand. Eventually, the government relented. The 1977 National Civic Strike would be the largest labor strike in Colombia in the 20th century.

Beyond this, the National Civic Strike has continued to have an important place in Colombian history, as something to aspire to and a demonstration of unity and grassroots power. Modern movements look to it for inspiration, just as they look to carimañolas for sustenance.

Carimañolas are delicious! Make sure you cook them for long enough, or you might have a mashed potato consistency instead.

Carimañolas Recipe

Carimañolas are savory, torpedo-shaped fritters made from mashed yuca (cassava) dough, typically filled with seasoned ground meat or cheese, and then fried until golden brown.

• Yields: 12–15 carimañolas

• Prep Time: 30 minutes

• Cook Time: 30–40 minutes

Ingredients

For the Yuca Dough:

• 2 lbs fresh yuca, peeled and cut into 2–3 inch pieces (or 2 lbs frozen yuca, thawed)

• 1 teaspoon salt

• 2 tablespoons butter, melted

• 1 egg, lightly beaten (optional, helps with binding)

• ¼ cup all-purpose flour (optional, for extra binding if needed)

For the Meat Filling (Pino de Carne):

• 1 lb ground beef or pork

• 1 tablespoon olive oil

• ½ small onion, finely diced

• 2 cloves garlic, minced

• ½ red bell pepper, finely diced (optional)

• 2 tablespoons tomato paste

• ½ teaspoon ground cumin

• ¼ teaspoon ground oregano

• Salt and pepper to taste

• ¼ cup beef broth or water (optional)

For Frying:

• Vegetable oil or canola oil for deep frying

Instructions

1. Prepare the Yuca:

• Place the peeled yuca pieces in a large pot and cover with water. Add ½ teaspoon of salt. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer until the yuca is very tender when pierced with a fork (about 15–25 minutes, depending on the yuca).

• Drain the yuca thoroughly. While still hot, transfer to a large bowl.

• Mash the yuca with a potato masher or a fork until smooth. It’s crucial to remove any fibrous threads that run down the center of the yuca pieces as you mash.

• Add the melted butter and the remaining ½ teaspoon of salt to the mashed yuca. If using, add the beaten egg and flour. Mix well until you have a smooth, pliable dough. Cover the dough with a damp cloth to prevent it from drying out.

2. Prepare the Meat Filling:

• In a skillet, heat the olive oil over medium heat. Add the diced onion, bell pepper (if using), and minced garlic. Sauté until softened, about 5–7 minutes.

• Add the ground beef (or pork) to the skillet, breaking it up with a spoon. Cook until browned. Drain any excess fat.

• Stir in the tomato paste, cumin, oregano, salt, and pepper. If the mixture seems too dry, add a splash of beef broth or water.

• Cook for another 5–7 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the flavors are well combined and the mixture is slightly thickened. Remove from heat and let cool slightly.

3. Assemble the Carimañolas:

• Take a portion of the yuca dough (about 2 tablespoons) and roll it into a ball.

• Using your thumb or finger, make a deep indentation in the center of the ball, creating a cavity.

• Spoon about 1–2 tablespoons of the meat filling into the cavity.

• Carefully bring the edges of the yuca dough together to enclose the filling. Gently shape the carimañola into a torpedo or elongated oval shape, making sure the filling is completely sealed inside. Repeat with the remaining dough and filling.

4. Fry the Carimañolas:

• Heat enough vegetable oil in a deep pot or Dutch oven to a temperature of 350–375°F (175–190°C).

• Carefully place the carimañolas into the hot oil in batches, being careful not to overcrowd the pot.

• Fry for 5–8 minutes, turning occasionally, until they are golden brown and crispy on all sides.

• Remove the carimañolas with a slotted spoon and place them on a paper towel-lined plate to drain excess oil.

• Serve hot, perhaps with a side of aji or sour cream.

Bandeja Paisa: Platters and Powder

Bandeja Paisa is a breakfast platter most associated with the Antioquia region of Colombia, home to the country’s second-largest city: Medellín. Originally a farmer’s meal, meant to power a full day in the fields, it evolved into a culinary icon of the region. With chorizo, avocado, eggs, fried pork skin (chicharrón), arepas, sweet plantain, ground beef, and beans, it’s Colombia’s answer to the Full English Breakfast. It often vies with the arepa for the title of Colombia’s national dish. But one thing is certain: this platter is Medellín on a plate.

Unfortunately, by the 1970s and 1980s, Medellín became known for something else entirely: as the heart of the global cocaine trade.

In the 1970s, Pablo Escobar founded the Medellín Cartel. Building on existing smuggling routes, once used for everything from fake diplomas to stereo equipment, Escobar saw the immense profit cocaine offered. His empire sourced coca paste from Peru and Bolivia, processed it in the Colombian jungle, and flew product directly to the U.S., with Medellín as the nerve center.

The cocaine trade made Escobar one of the wealthiest men in history. To stay on top, the Medellín Cartel turned to mass murder and bribery. The city earned its grim title as the murder capital of the world, with the cartel killing judges, politicians, rival traffickers, defectors, and countless civilians caught in the crossfire. While Medellín’s economy collapsed and fear gripped the streets, Escobar cast himself as a Robin Hood, building schools and libraries in the slums to launder his reputation and to build an army of loyalists in the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

During this era of chaos, bandeja paisa emerged as more than just a regional dish. It became a symbol of resilience. In neighborhoods under siege, working-class families clung to the dish that defined them. They gathered around plates of fried plantain, chorizo, and beans not just for nourishment but to remind themselves of who they were. Bandeja Paisa was Medellín, and they weren’t giving it up.

Of course, Escobar wasn’t the only one killing working-class Colombians. The government, the Cali Cartel, and the U.S. DEA played their roles. And in the late 1980s, the Colombian state, with CIA backing, unleashed paramilitary death squads to wage a brutal war not just on Escobar but on anyone in the slums who might oppose them.

In the early 90s, the right-wing paramilitary group Muerte a Secuestradores (MAS), a group formed to protect rich Colombians from guerrilla and drug lord violence, began targeting poor neighborhoods in Medellín at the behest of the DEA and Colombian government to cut off Escobar’s means of recruitment. One particular poor neighborhood, Comuna 13, was a hotbed of Cartel activity but also of left-wing guerrilla activity. They went above and beyond targeting the cartel and guerrillas, beginning “social cleansing operations” in the slum, killing homeless people and drug addicts. In 1993 alone, 2,190 street children were murdered by right-wing paramilitaries while targeting Escobar.

Despite the neighborhood being targeted by paramilitary groups, narcos, and police, street vendors in Comuna 13 continued to serve bandeja paisa during the “Medellín Massacre,” often putting themselves in danger to do so. They refused to let Medellín lose itself.

In 1993, Escobar was killed in Medellín by Colombian National Police. 25,000 attended his funeral.

Medellín itself would recover, now known as an art and culture hub. Pablo Escobar’s house is now a theme park. Right-wing paramilitaries continued to be a scourge on the countryside for years to come. Bandeja paisa is now a tourist food, an icon of Medellín’s dark past and its bright present.

Bandeja Paisa is delicious! Just make sure you save room.

Bandeja Paisa Recipe

Bandeja Paisa is a massive, traditional Colombian platter, often considered the national dish. It’s a feast of flavors and textures, typically including a variety of meats, rice, beans, plantains, and more.

• Yields: 4 servings

• Prep Time: 30 minutes

• Cook Time: 2–3 hours (due to various components)

Ingredients

For the Beans (Frijoles):

• 1 ½ cups red kidney beans (dried), soaked overnight

• 4 cups water or chicken broth

• ½ small onion, diced

• 2 cloves garlic, minced

• 1 tablespoon hogao (see recipe below) or a little oil

• Salt and pepper to taste

For the Ground Beef (Carne Molida):

• 1 lb ground beef

• 1 tablespoon oil

• ½ small onion, finely diced

• 1 clove garlic, minced

• ½ teaspoon ground cumin

• Salt and pepper to taste

For the Chicharrón (Crispy Pork Belly):

• 1 lb pork belly, cut into thick strips

• Salt

For the Chorizo:

• 4 Colombian chorizos (or other good quality pork sausage)

For the Fried Egg (Huevo Frito):

• 4 large eggs

• Oil for frying

For the Arepas:

• 4 small arepas (use the Arepas con Queso recipe, omitting the cheese in the center if preferred, or simply make plain arepas)

For the Sweet Plantains (Tajadas de Plátano Maduro):

• 2 ripe plantains, peeled and sliced diagonally

• Oil for frying

Accompaniments:

• 4 cups cooked white rice

• 1 large avocado, sliced

• Lime wedges (optional)

Instructions

1. Prepare the Beans: Drain the soaked beans. In a large pot or pressure cooker, combine beans with 4 cups of water or broth. Cook until very tender (about 1–2 hours in a regular pot, 30–40 minutes in a pressure cooker).

• In a separate small pan, heat a little oil or hogao. Sauté the diced onion and minced garlic until softened. Add this mixture to the cooked beans. Season with salt and pepper. Continue to simmer gently to allow flavors to meld, mashing a few beans against the side of the pot to thicken the broth if desired.

2. Prepare the Chicharrón: Score the skin of the pork belly. Season generously with salt.

• Preheat oven to 400°F (200°C). Place pork belly, skin-side up, on a baking sheet. Bake for 30 minutes, then reduce heat to 325°F (160°C) and continue baking for 1–1.5 hours, or until the fat has rendered and the skin is crispy. You can also fry it in a deep pot with oil over medium-high heat until crispy.

3. Prepare the Ground Beef: In a skillet, heat 1 tablespoon of oil over medium heat. Add diced onion and sauté until translucent. Add minced garlic and cook for another minute.

• Add the ground beef, breaking it up with a spoon. Cook until browned. Drain any excess fat.

• Stir in ground cumin, salt, and pepper. Cook for a few more minutes until beef is fully cooked and seasoned.

4. Cook the Chorizo: In a separate pan, cook the chorizos over medium heat until browned and cooked through. You may need to prick them with a fork to release fat.

5. Cook the Arepas: Prepare the arepas according to the recipe above, cooking them on a griddle until golden.

6. Fry the Sweet Plantains: In a skillet, heat enough oil to cover the bottom over medium-high heat. Fry the plantain slices until golden brown and caramelized on both sides. Drain on paper towels.

7. Fry the Eggs: In a small skillet, fry the eggs sunny-side up or to your preference.

8. Assemble the Bandeja Paisa: On a large platter, arrange all the components: a generous serving of white rice, a portion of beans (with some broth), ground beef, chicharrón, chorizo, a fried egg (often placed on top of the rice), sweet plantains, sliced avocado, and an arepa. Serve immediately with lime wedges if desired.

Tajadas de Plátano Maduro: Bitter Sweetness

Plantains are not actually native to the Americas. Most likely, they were brought by African slaves, who were trying to keep a piece of home. Nonetheless, they adapted brilliantly to the tropical climate of Central and South America. They are eaten both ripe and unripe. However, the ripe kind are sweeter, and in Colombia, fried slices of the ripe sweet plantains are called Tajadas de Plátanos Maduros. They are associated closely with Afro-Colombian cuisine, and even as Afro-Colombians were displaced from their homes, these sweet plantain slices remained a connection.

Urabá is in the far Northwest of Colombia, bordering Panama, the Caribbean Sea, and the Pacific Ocean. It is the seat of Afro-Colombian culture and cuisine, the country’s biggest banana-producing region, and an area with substantial other natural resources.

By the middle of the 1990s, many of the right-wing paramilitaries had joined together under the umbrella of the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (or Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia or AUC). Many of these groups formed originally to defend Colombia’s landowning elite from peasant guerrilla organizations like the FARC and drug lords from rival drug traffickers. They remained linked to these organizations as the Colombian military utilized them to fight Pablo Escobar and take the fight to left-wing guerrilla groups such as the FARC.

Colombia’s business elite wanted these copious natural resources for themselves and would pay these paramilitaries to secure these regions, intimidating the indigenous people and Afro-Colombians to leave under the ostensible reason of trying to root out left-wing guerrillas. The Chiquita Banana company even paid the AUC to act as security and enforcement on their plantations, discreetly sending them to torture union leaders and kick people off their land for banana plantation expansions. This is why I’ve taken to calling bananas “conflict plantains” in everyday lingo.

But the single biggest tragedy happened in 1996. Backed by the military and agribusiness, the AUC targeted Urabá’s Jiguamiandó and Curvaradó river basins to seize land for palm oil plantations. Operations Genesis and Cacarica (1996–1997) saw paramilitaries and soldiers burn villages, massacre civilians, and displace over 15,000 Afro-Colombians, many fleeing to urban slums in Bogotá and Medellín.

Afro-Colombians, now without a home, would find themselves frying up Tajadas de Plátanos Maduros in makeshift camps throughout Colombia‘s rural regions, alleys in cities, and wherever they might find themselves, trying to hold onto a taste from home.

By 2009, over 288,000 Afro-Colombians had been displaced, with that number probably higher due to it being self-reported. The arrangements between big business and paramilitary groups took many years to come to light, with Chiquita finally getting in trouble with the US government for funding a terrorist organization in the late 2000s. Wherever the Afro-Caribbean people go, whether it be home or far away, Tajadas remain as a reminder of their home. Nowadays, they are often cooked at gatherings as people plan legal strategies to get their land back.

Traditionally, these are sweet enough that you can just fry in oil. However, I like to drizzle honey and grated Parmesan cheese over them.

Tajadas de Plátano Maduro Recipe

• Yields: 4 servings (as a side/snack)

• Prep Time: 5 minutes

• Cook Time: 10 minutes

Ingredients

• 2–3 very ripe plantains (yellow with black spots)

• 1–2 cups vegetable oil (for frying)

• Optional: a pinch of salt, cinnamon sugar, or a drizzle of honey

Instructions

1. Prepare the plantains: Peel the ripe plantains. You can do this by slicing a shallow cut lengthwise across the peel and then peeling it off. Cut the plantains into 1/2-inch thick slices. You can cut them straight or on a diagonal for more surface area.

2. Heat the oil: In a large frying pan, heat the vegetable oil over medium to medium-high heat. You’ll want enough oil so that it’s at least an inch deep, or deep enough to submerge the plantain slices partially.

3. Fry the plantains: Carefully add the plantain slices to the hot oil in a single layer, being careful not to overcrowd the pan. Cook for about 2–3 minutes per side, or until golden brown and caramelized. They should be soft in the center with slightly crispy edges.

4. Drain: Once cooked, remove the plantains from the oil with a slotted spoon and transfer them to a plate lined with paper towels to drain excess oil.

5. Serve: Serve warm as a side dish or snack. You can sprinkle with a little salt, cinnamon sugar, or drizzle with honey for extra flavor, if desired.

Patacones con Hogao: Smashed and Sizzling

Unripe, starchy plantains, fried, smashed, and fried again are a staple of Latin American cuisine. Most countries call them tostones. However, in Colombia, they are known as patacones. Also in Colombia, they are often served with this tomato and onion sauce called hogao sauce. Hogao sauce is very much a Colombian take on Salsa or Sofrito and is most often associated with the coastal cities like Cali and Medellín area. Of course, in 2021, Cali became ground zero for a national protest movement.

In 2021, Colombia was facing the third highest death rate from COVID-19, the government was planning on raising taxes on the poor to pay for COVID-era social programs, and the government was planning on privatizing their public healthcare system. Two years before, in 2019, Colombians had a national strike against austerity measures proposed by this same president, Iván Duque, and were looking to perform a repeat. There was also an undercurrent of addressing corruption, with protesters demanding former president Álvaro Uribe face charges of crimes against humanity for his use of paramilitary groups to kill civilians and reigning in police brutality within Colombia.

Seeing protests coming, Colombia’s high court banned public protest due to COVID. However, this ruling was ignored, with people coming out in the tens of thousands to protest. Community kitchens were set up by mutual aid networks, with protesters being served patacones out of styrofoam containers that were delivered to the front lines.

Cali’s Puerto Resistencia (name change from Puerto Rellena) became a symbol of defiance. State repression was brutal: at least 46 were killed, hundreds injured, and over 1,200 detained, with Afro-Colombian and working-class communities bearing the brunt.

As police and paramilitary forces targeted Cali’s working-class neighborhoods, the community kitchens continued to pump out patacones, a taste of coastal resilience that refused to be silenced. These shared meals strengthened bonds, with protesters planning strategies over steaming plates, their spirits unbroken despite the violence.

The protests worked, and the tax reforms were withdrawn, the health care proposals were withdrawn, and the protests exposed significant instances of police brutality. A left-winger, Gustavo Petro, won the presidency in 2022, the first in Colombia’s recent history. Structural issues of inequality remain, but patacones remain a taste of the coast that can be enjoyed by all.

I’ve made tostones many times. I must say the hogao sauce really makes them pop.

Patacones con Hogao Recipe

Patacones are crispy, twice-fried green plantain slices. Hogao is a savory Colombian creole sauce made with tomatoes and onions, perfect for dipping.

• Yields: 4 servings

• Prep Time: 15 minutes

• Cook Time: 20–30 minutes

Ingredients

For the Patacones:

• 3–4 green plantains (very unripe, firm, and green)

• Oil for frying (vegetable, canola, or corn oil)

• Salt to taste

• Optional: Garlic water (1 cup water + 1 clove minced garlic + ½ tsp salt) for dipping

For the Hogao:

• 2 large ripe tomatoes, finely diced or grated

• 1 medium yellow onion, finely diced

• 2 cloves garlic, minced (optional)

• 2 tablespoons olive oil (or vegetable oil)

• Salt and pepper to taste

• ½ teaspoon ground cumin (optional)

• ½ teaspoon achiote powder or annatto oil (for color, optional)

Instructions

1. Prepare the Hogao:

• In a medium skillet, heat the olive oil over medium heat.

• Add the finely diced onion and sauté until translucent, about 5–7 minutes.

• Add minced garlic (if using) and cook for another minute until fragrant.

• Stir in the diced or grated tomatoes. If using achiote or cumin, add them now.

• Season with salt and pepper.

• Reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer for 15–20 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the vegetables are very soft and the sauce has thickened slightly. Remove the lid for the last 5 minutes if it’s too watery. Taste and adjust seasoning. Set aside.

2. Prepare the Patacones (First Fry):

• Peel the green plantains. It can be tricky, so use a knife to score the peel lengthwise and then pry it off with your fingers.

• Cut the peeled plantains into 1-inch thick rounds.

• Heat enough oil in a deep skillet or Dutch oven to submerge the plantain pieces (about 1–2 inches deep) to 300–325°F (150–160°C).

• Carefully add the plantain pieces to the hot oil. Fry for about 5–7 minutes, or until they are tender and light yellow, but not browned or crispy yet.

• Remove the plantains from the oil and place them on a paper towel-lined plate to drain.

3. Smash the Patacones:

• While still warm, smash each plantain piece. You can do this by placing a piece between two sheets of plastic wrap or parchment paper and pressing down with the bottom of a heavy pan, a plate, or a specialized plantain press (tostonera). Flatten them to about ¼ inch thick.

• If using garlic water, quickly dip each smashed plantain into the garlic water before the second fry. This adds flavor and can help with crispiness.

4. Prepare the Patacones (Second Fry):

• Increase the oil temperature to 350–375°F (175–190°C).

• Return the smashed plantains to the hot oil in batches, being careful not to overcrowd the pan.

• Fry for another 3–5 minutes per side, or until golden brown and very crispy.

• Remove the patacones from the oil and immediately place them on paper towels to drain excess oil. Season generously with salt while they are still hot.

5. Serve: Arrange the crispy patacones on a serving platter and serve hot with the hogao for dipping.

Comments

Post a Comment