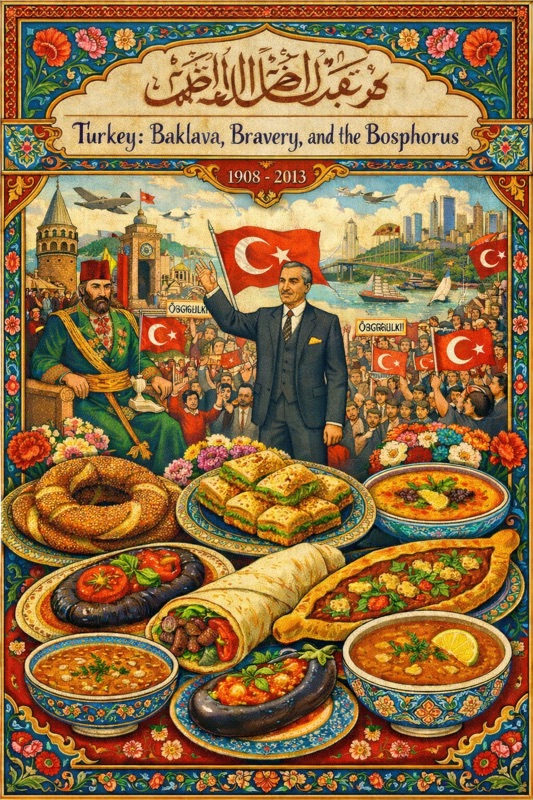

Turkey: Baklava, Bravery, and the Bosphorus

Turkey: Baklava, Bravery, and the Bosphorus

Turkey sits at the hinge of the world, where Europe meets Asia, where the call to prayer echoes across old Byzantine domes, where empires have risen, fallen, and left their layers behind like sediment in a long-simmering stew. It is a land shaped by sultans and soldiers, poets and peasants, merchants and migrants, revolutions and quiet resistances. For centuries, the Ottoman Empire ruled vast stretches of the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and the Middle East, a patchwork of peoples and faiths held together by bureaucracy, janissaries, and a surprisingly flexible imperial system. But by the late 1800s, that world was cracking. Reformists called for constitutionalism. Workers and students dreamed of a modern nation. Ethnic minorities demanded equality. And through it all, the empire’s grand kitchens kept turning, spinning dough, roasting meats, layering pastry, and feeding the crowds who would soon reshape history.

The 20th century was a whirlwind. The Young Turks swept into power with promises of equality and modernization. World War I fractured the empire for good. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk led a war for independence and built a secular republic from the rubble. But republic did not mean rest. Turkey moved through decades of coups, strikes, protests, mass mobilizations, and reinventions of its national identity. Workers marched. Students occupied campuses. Kurds demanded recognition. Farmers, intellectuals, and city-dwellers all clashed over what Turkey was, and what it should become. Taksim Square became a stage for democracy, repression, and rebirth. And through it all, through every rupture, every uprising, every hopeful spring, Turkish food fed the people who lived it.

Because to tell the story of Turkey, you need to talk about its food. Simit sellers at dawn, slinging sesame-crusted rings to factory workers before a morning strike. Doner spits turning under flickering neon lights as students planned marches. Plates of baklava passed around cramped union halls. Stews simmering in village kitchens while workers debated the future. Menemen bubbling on street corners as protesters caught their breath.

This post is a walk through Turkey’s modern political history, told through the dishes that nourished rebellion.

We begin in 1908, with Simit, the street bread of Istanbul, sustaining crowds during the Young Turk Revolution and the wave of great strikes that followed.

We move to Baklava, served and shared during the hopeful early 1960s, when Workers’ Day and the rise of collective solidarity gave Turkish labor a powerful voice.

Then comes the Döner Dürüm Wrap, the fuel of factory workers resisting mass layoffs and repression in the turbulent Workers’ Resistance of 1970.

We sit with İmam Bayıldı, a dish of soft eggplant and simmered onions, tied here to the grief and fury of the 1977 May Day Massacre, one of the darkest days in Turkey’s democratic struggle.

We stretch dough for Pide, warm and hearty, eaten by workers during the 1989 Bahar Eylemleri (Spring Actions), a massive wave of strikes and demonstrations across the country.

We stir Ezogelin Çorbası, the humble but nourishing lentil soup that powered miners and their families during the 1991 Zonguldak Miners’ March, one of the largest labor mobilizations in Turkish history.

And finally, we crack eggs into tomatoes and peppers for Menemen, tied to the 2013 Gezi Park Protests, when environmentalists, students, artists, workers, and everyday citizens transformed a small park demonstration into a nationwide call for dignity and democracy.

These dishes are delicious. They are also political. They tell the story of a nation forever negotiating its past, defending its future, and feeding its people along the way.

So start spinning the rotisserie. Warm the bread. Pour the tea.

Let’s begin.

Simit: Circles of Bread, Circles of Revolt

Simit, the sesame-crusted bread ring sold from wooden carts and shoulder trays across Istanbul, Salonica, and the port cities of the eastern Mediterranean, is among the oldest and most democratic foods of the Ottoman world. Cheap, filling, portable, and endlessly repeatable, it belongs to no palace kitchen and no single region. Its circular shape, unbroken, continuous, made it a quiet companion to the rhythms of daily life: the walk to the docks, the morning shift at the press, the long wait at the barracks gate. In 1908, when the Ottoman Empire convulsed with strikes, mutinies, and revolution, simit became more than breakfast. It became fuel for a constitutional uprising and an edible emblem of collective solidarity.

The origins of simit stretch back centuries. Ottoman court records from the 16th century already mention simitçi, licensed bread sellers regulated by the state. The dough, wheat flour, water, yeast, was dipped in grape molasses (pekmez), rolled in sesame seeds, and baked until deeply browned. Unlike loaves, simit traveled well. Unlike pastries, it did not require luxury ingredients. It was designed for movement: eaten while walking, torn and shared, passed hand to hand. This portability made it ideal for a city whose economy depended on circulation, of goods, of people, of ideas.

By the late 19th century, simit had become inseparable from urban working-class life. Dockworkers ate it at dawn. Railwaymen stuffed it into coat pockets. Students gnawed on it between lectures. Soldiers bought it from street vendors outside barracks walls. It was sustenance without ceremony, a bread of the street rather than the home. And it was precisely this quality that would make simit so visible in moments of mass political action.

To understand why simit mattered in 1908, one must understand the Ottoman world it fed. By the late 1800s, the empire was weakened (The Sick Man of Europe) but not inert. Reforms known as the Tanzimat (1839–1876) had attempted to modernize the state, centralizing administration, reorganizing the military, expanding education, and promising legal equality. But these reforms also brought new contradictions: heavier taxation, deeper debt to European creditors, and growing inequality between elites and workers. Railways and ports expanded, but wages stagnated. Newspapers multiplied, but censorship tightened.

In 1876, amid crisis and unrest, the Ottomans adopted their first constitution. It promised a parliament and limits on the sultan’s power. Within two years, Sultan Abdulhamid II suspended it, dissolved parliament, and ruled as an autocrat. For three decades, Abdulhamid presided over a vast surveillance state, censoring the press, exiling dissidents, and relying on secret police to maintain control. Yet even as political life was frozen, economic and social life accelerated. The empire urbanized. A wage-earning working class expanded in docks, railways, factories, and printing houses. These workers ate simit.

Opposition to Abdulhamid coalesced among intellectuals, officers, and professionals, many of them operating in exile. They called themselves the Young Turks. Their central demand was simple and explosive: the restoration of the 1876 constitution. But their ideas circulated not just through pamphlets and conspiracies, but through the daily lives of ordinary people, through conversations in cafés, workshops, and street corners where simit crumbs gathered on wooden counters.

In July 1908, the dam broke. Mutinies by reformist officers in Macedonia triggered a cascade of unrest. Faced with the threat of civil war, Abdulhamid capitulated. On July 24, 1908, the constitution was restored. Censorship collapsed overnight. Newspapers exploded in number. Political clubs formed. Crowds filled the streets of Salonica and Istanbul in celebration. Simit vendors did brisk business, their trays surrounded by jubilant civilians and soldiers alike, all participants in what felt like a rebirth.

But the revolution did not stop at constitutional restoration. Almost immediately, the streets filled again, this time not with celebration, but with strikes. The lifting of censorship and police repression unleashed years of accumulated grievances. Workers who had long been silenced now spoke collectively. Dockworkers, railwaymen, tram operators, printers, tobacco workers, and textile laborers walked off the job. In the months following July 1908, more than 100,000 workers across the empire participated in strikes, often spontaneously, often without formal unions.

These strikes shared certain characteristics. They were urban, public, and collective. Workers gathered at factory gates, port entrances, and railway yards. They marched through streets, held assemblies, and occupied workplaces. And throughout it all, simit circulated. Vendors followed crowds. Strikers bought bread in bulk, breaking rings into halves and quarters. The same bread passed between Muslims, Christians, Jews; Turks, Greeks, Armenians, Slavs. In cities like Salonica, a polyglot, industrial port and hotbed of Young Turk organizing, simit became common ground, the cheapest way to keep bodies standing during long days of protest.

The alliance between soldiers, workers, and intellectuals, so central to the success of the 1908 Revolution, was visible in these everyday exchanges. Soldiers sympathetic to constitutionalism shared simit with striking workers. Students debated politics while eating it on sidewalks. Bread bridged the gap between ideology and survival. A revolution, after all, must eat.

The immediate aftermath was chaotic and hopeful. New political parties emerged, most notably the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which would dominate Ottoman politics. Parliament reconvened. Labor organizations formed, and strike activity continued into 1909. Not all outcomes were progressive. Counter-revolutionary violence erupted in April 1909, leading to massacres and instability. Abdulhamid was deposed, replaced by Mehmed V. The promise of constitutional harmony collided with ethnic tensions, imperial decline, and the pressures of global capitalism.

Yet the political culture had changed irrevocably. Mass participation was now thinkable. Workers had learned their collective power. Food had played its quiet role. Simit had been there at every stage, during celebration, during confrontation, during uncertainty.

The following decade would be brutal. The empire staggered through the Balkan Wars, then World War I. Famine stalked the cities. Bread became scarcer, more politicized. Still, simit endured, its price and availability often a subject of public anger. When the Ottoman Empire finally collapsed after defeat in 1918, and the Turkish War of Independence followed, the habits of street life remained. Vendors still carried rings of bread through ruined streets.

In 1923, the Republic of Turkey was proclaimed. It was a new state born from imperial wreckage, nationalist struggle, and revolutionary memory. Its founding myths emphasized soldiers and statesmen, but beneath them lay older, quieter stories: of workers who struck, of streets that filled, of hunger endured together. Simit survived the transition intact. It remained what it had always been, bread of the people, eaten standing up, often in company.

In the end, the revolution came full circle. The constitution returned. The empire fell. A republic emerged. And through it all, the bread ring remained, unbroken, passed from hand to hand, a reminder that political change is always grounded in the ordinary needs of ordinary people.

Simit reminds me of a chewy, twisty bagel. I love them!

Simit (Sesame Bread Rings)

Description: Turkish golden, crisp sesame-coated bread rings commonly enjoyed with tea.

Makes: 6 simit

Ingredients:

Dough:

- 3 cups flour

- 1 tbsp sugar

- 1 tsp salt

- 1 tbsp active dry yeast

- 1 cup warm water

- 2 tbsp olive oil

Coating:

- ½ cup grape molasses (pekmez) or honey diluted 1:1 with water

- ½ cup water

- 1 cup toasted sesame seeds

Instructions:

- Make Dough: Proof yeast with warm water and sugar. Mix with flour, salt, and oil. Knead 8–10 minutes until smooth. Rise 1 hour until doubled.

- Shape: Preheat oven to 425°F (220°C). Divide dough into 6 pieces. Roll each into 50cm ropes, twist pairs together, and join ends into rings.

- Coat & Bake: Mix molasses with water for dip. Dip rings in mixture, then coat in sesame seeds. Bake 15–20 minutes until golden.

- Serve: Enjoy fresh or at room temperature with tea and cheese.

Tips: Toasting sesame seeds intensifies flavor.

Baklava: Layers of Law, Layers of Labor

Baklava is often imagined as timeless: a gleaming tray of syrup-soaked pastry, its diamond cuts precise, its surface shimmering with butter and pistachio dust. It is associated with celebration, hospitality, and abundance, weddings, holidays, births, and religious feasts. Yet baklava’s history is anything but static. Baklava’s origins predate the Turkish Republic by centuries. Its ancestral forms stretch across Central Asia, Persia, and the eastern Mediterranean, thin doughs layered with fat and nuts, baked and sweetened. In the Ottoman world, baklava reached its most elaborate expression. By the 16th century, it was firmly associated with the imperial court. The Topkapı Palace kitchens perfected its geometry and ritualized its production. Each year during Ramadan, trays of baklava were prepared for the Baklava Alayı, the ceremonial procession in which janissaries received the dessert from the sultan. This was not merely food; it was hierarchy made edible. Each layer of dough mirrored the layers of empire. Butter, sugar, and nuts, expensive ingredients, signaled privilege and order.

Yet even in the Ottoman period, baklava was never confined entirely to the palace. Artisans, guilds, and urban households adapted it, simplifying ingredients or stretching portions. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, baklava shops appeared in cities like Istanbul, Gaziantep, and İzmir. As industrial sugar became cheaper and urban wages stabilized, baklava slowly lost its exclusive aura. It remained special, but it was no longer forbidden. Like the political culture shaped by the 1908 Revolution, it moved outward, from elite ritual toward public life, before it finally became the ultimate celebratory food for workers in 1961.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the birth of the Turkish Republic in 1923 marked a profound rupture. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his allies sought to create a modern, secular, nationalist state from imperial wreckage. The new republic abolished the sultanate and caliphate, reformed law, language, dress, and education, and centralized power aggressively. These reforms reshaped daily life, including food culture. Palace kitchens disappeared; state institutions replaced imperial ones. Yet the republic was not a workers’ democracy. Political pluralism was limited. Independent unions were constrained. Strikes were discouraged or banned outright in the name of national unity and development.

Throughout the single-party period (1923–1946), the state promoted an image of harmony between classes. Labor conflict was framed as divisive or foreign-inspired. Workers existed, but as abstract contributors to national progress rather than organized political actors. Baklava, during this period, settled into a new role. It became a staple of family celebration and neighborhood life, served at circumcisions, weddings, and religious holidays. It was no longer imperial, but it was not yet political. Its sweetness marked private joy rather than public struggle.

After World War II, pressures mounted. Turkey’s economy strained under rapid urbanization and uneven development. Rural migrants flooded cities, forming a growing industrial workforce. Internationally, Cold War alignments pushed Turkey toward multiparty politics and closer ties with the West. In 1950, the Democrat Party came to power, ending decades of single-party rule. Initially popular, the government pursued liberal economic policies and infrastructure expansion, but also curtailed press freedom, repressed opposition, and increasingly relied on police power to silence dissent. By the late 1950s, inflation rose, debt deepened, and political polarization sharpened.

On May 27, 1960, the military intervened. The coup overthrew the Democrat Party government, arrested its leaders, and suspended the constitution. Coups are often remembered only for repression, but this one produced a paradox. While brutal in its immediate aftermath, including executions, it also opened space for a new constitutional order. The military junta, seeking legitimacy, convened a constituent assembly. The result was the 1961 Constitution, one of the most liberal in Turkish history.

For workers, its significance was immense. For the first time, the constitution explicitly recognized the right to form unions, to strike, and to engage in collective bargaining. Social rights, education, welfare, labor protections, were written into law. The language of class, long suppressed, reentered public discourse. Workers were no longer merely contributors to national development; they were political subjects.

It was in this context that May Day returned to public life.

International Workers’ Day had deep roots in Turkey, dating back to Ottoman labor movements and the strikes of the early 20th century. But it had been banned, restricted, or driven underground for decades. In 1961, for the first time since the republic’s early years, May 1 was openly celebrated again. Workers gathered in Istanbul, Ankara, and İzmir, not in defiance, but with permits in hand. Banners demanded fair wages, job security, and dignity. Speeches echoed through public squares. It was not a revolution, but it felt like a turning point.

And people brought food.

Baklava marked recognition of the moment. It appeared on tables at union offices, in metal trays carried to parks, cut carefully and shared. Some was homemade, others purchased collectively from neighborhood pastry shops. It was served after marches, during meetings, at evening gatherings where workers and their families sat together. The symbolism was subtle but powerful. Baklava, once distributed from palace to soldiers as a sign of obedience, was now shared horizontally among workers as equals.

The aftermath of the 1961 May Day was mixed. Union membership surged. New labor federations formed. Strikes spread through factories, docks, and public services. A culture of collective action took root, supported by the constitutional framework. Yet the liberal moment was fragile. Employers resisted. Governments shifted. The military remained a looming presence. By the late 1960s and 1970s, labor militancy would intensify, and so would repression, culminating in further coups.

Still, something irreversible had happened. The idea that workers could gather openly, speak collectively, and claim rights as citizens had entered the social fabric. Like baklava itself, it was layered into memory, associated with moments of shared effort and earned sweetness.

Baklava needs no introduction. I personally prefer the Turkish version with pistachios.

Turkish Pistachio Baklava (Antep Style)

Description: Ultra-crisp layers of phyllo filled with finely ground pistachios, soaked in light syrup.

Serves: 12–15 pieces

Ingredients:

Syrup:

- 3 cups sugar

- 1 ½ cups water

- 1 tbsp lemon juice

- 1 tsp rose or orange blossom water (optional)

Baklava:

- 1 lb (450g) phyllo dough (about 40 sheets)

- 2–2½ cups finely ground pistachios

- 1 cup clarified butter or ghee

- 2 tbsp crushed pistachios (for garnish)

Instructions:

- Make Syrup (Cool Completely): Simmer sugar and water 10–12 minutes. Add lemon juice; simmer 2 minutes. Add flower water if using. Cool fully.

- Prep Phyllo: Keep covered with a damp towel. Trim to fit pan if needed.

- Clarify Butter: Melt butter, skim foam, and use clear fat.

- Layer: Butter a baking pan. Layer 15–20 buttered phyllo sheets. Spread half the pistachios. Add 5–7 buttered sheets. Spread remaining pistachios. Top with 15–20 buttered sheets.

- Cut: Cut into diamonds or squares before baking.

- Bake: 325°F (165°C) for 55–70 minutes until deep golden.

- Add Syrup: Pour cold syrup over hot baklava.

- Rest: 4–6 hours or overnight.

- Garnish: Sprinkle crushed pistachios.

Döner Dürüm: Rolling Resistance

Döner, like many of these dishes, long predates the Turkish Republic. The technique of stacking seasoned meat on a vertical spit and shaving it as it roasted evolved in the late Ottoman period, particularly in Anatolia in the 19th century. Earlier forms were horizontal, cağ kebabı in Erzurum being the clearest ancestor, but the vertical spit was a technological and urban adaptation, saving space and allowing continuous service. Döner was efficient, modular, and scalable, perfectly suited to cities growing denser by the year. What changed over time was not just the meat, but how it was eaten.

The dürüm, meat wrapped in thin flatbread rather than plated or stuffed into a loaf, was a further step toward portability. Lavash or yufka replaced plates and cutlery. The wrap could be held in one hand, eaten standing, finished quickly, or folded away for later. By the 1960s, döner dürüm had become a worker’s meal par excellence: cheap, filling, fast, and available near factories, bus terminals, docks, and construction sites. It was sustenance designed for people whose time was not their own, and in 1970, these people would need to make a statement.

The Turkey that emerged from the hopeful moment of 1961 changed rapidly. The new constitution had legalized strikes and collective bargaining, and workers used those rights aggressively. Union membership expanded, particularly under the Confederation of Revolutionary Trade Unions (DİSK), founded in 1967 by unions dissatisfied with the more conservative Türk-İş. The late 1960s saw a surge of labor militancy: factory occupations, wildcat strikes, and solidarity actions that crossed sectors. Industrialization accelerated, especially around Istanbul, Kocaeli, and İzmit. Migrants from Anatolia poured into shantytowns, becoming the backbone of a growing industrial workforce.

But the same state that had legalized labor rights remained deeply suspicious of their use. Employers complained that unions were becoming too powerful. Conservative politicians warned of “chaos” and “communist infiltration.” The military, ever-present since 1960, viewed mass politics with unease. As the decade wore on, governments changed frequently, coalitions collapsed, and instability became the pretext for rollback.

The breaking point came in 1970. The ruling Justice Party government proposed amendments to the Trade Unions Law and the Collective Bargaining, Strike, and Lockout Law. Framed as technical reforms, their purpose was clear: to weaken DİSK by making it nearly impossible for workers to switch unions and by raising thresholds for collective bargaining authority. In effect, the laws would have frozen union representation in favor of state-aligned federations and neutralized the most militant segments of the labor movement. Rights would still exist, but only for unions that posed no threat.

Workers understood this immediately. The issue was not abstract legality; it was survival as a collective force. If the laws passed, DİSK would wither, shop by shop, contract by contract. The constitutional promise of 1961 would remain intact in theory while being dismantled in practice. The response was swift and unprecedented.

On June 15, 1970, tens of thousands of workers walked out of factories across Istanbul and the industrial towns of the Marmara region. They did not gather in a single square. They moved. Columns of workers marched from Levent, Kartal, Alibeyköy, and Gebze, converging on bridges, highways, and industrial arteries. Ferries stopped. Traffic halted. Factories fell silent. By the next day, June 16, the number of participants exceeded 150,000.

This was not a symbolic protest; it was a mass workers’ resistance. Police barricades were breached. Bridges were blocked. In some areas, workers clashed directly with security forces. The state responded with force. Martial law was declared in Istanbul and Kocaeli. The army was deployed. Tanks appeared on streets built by the very labor now being suppressed. Several workers were killed. Hundreds were injured. Thousands were detained.

And throughout it all, people ate döner dürüm.

Food vendors did not organize the resistance, but they sustained it. Along march routes and near factory gates, döner stands stayed open as long as they could. Some vendors sold at cost. Others handed out wraps on credit, trusting they’d be paid later. The wrap itself mattered. There were no tables, no pauses long enough for a shared tray of sweets. Workers ate while walking, chewing as chants rose and fell. Grease soaked into paper. Bread absorbed sweat and sauce. The meal disappeared quickly, leaving only energy.

The state won the immediate confrontation. Martial law broke the marches. Leaders were arrested. Factories reopened under guard. But the resistance left scars that could not be erased. In December 1970, Turkey’s Constitutional Court annulled the offending amendments, ruling that they violated the constitution’s protections for union freedom. It was a rare admission that the workers had been right.

The victory was partial and temporary. Repression intensified in the following years. Political violence escalated. Another military coup would come in 1971, and a far more devastating one in 1980, which would crush unions, ban strikes, and remake Turkey’s economy along neoliberal lines. But June 15–16 could not be undone. It became a reference point—a moment when workers moved not as petitioners, but as a force capable of stopping the country.

Döner dürüm remained what it had always been: a cheap street meal. It did not become ceremonial. No anniversaries were marked with it intentionally. But memory does not require intention. For a generation of workers, the taste of shaved meat wrapped in bread became inseparable from the feeling of moving together through the city, of occupying streets normally reserved for cars, of realizing their numbers. It was the taste of urgency rather than celebration.

Chronologically, döner dürüm follows baklava naturally. Baklava belonged to the moment when rights were acknowledged and sweetness could be shared openly. Döner dürüm belongs to the moment when those rights had to be defended in motion, against the state itself. One is cut carefully and eaten seated. The other is wrapped tight and eaten on the run. One marks recognition; the other marks resistance.

Together, they tell the story of the 1960s in Turkey as it was lived from below: not as abstract constitutional debates or parliamentary maneuvers, but as bodies moving through streets, pausing briefly to eat, then moving again. If baklava was the taste of possibility, döner dürüm was the taste of refusal—the refusal to let hard-won layers of collective power be shaved away without a fight.

Oven Döner Kebab (Home-Friendly Dürüm Version)

Description: A home-friendly authentic Turkish döner kebab using a vertical skewer method. Serve wrapped in flatbread as dürüm.

Serves: 4

Ingredients:

Meat:

- 500g ground lamb or beef (or mix; 80/20 fat ideal)

- 1 small onion, finely grated

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 tsp ground cumin

- 1 tsp ground coriander

- 1 tsp smoked paprika

- 1 tsp dried oregano

- ½ tsp black pepper

- 1 tsp salt

- ½ tsp red pepper flakes (optional)

- 2 tbsp plain yogurt

For Serving (Dürüm):

- Flatbreads or lavash

- Sliced tomatoes, onions, lettuce

- Pickles (optional)

Yogurt–Tahini Sauce:

- ½ cup yogurt

- 1 tbsp tahini

- 1 tsp lemon juice

- Salt to taste

Instructions:

- Prepare Meat: Mix all meat ingredients vigorously by hand 4–5 minutes until sticky. Refrigerate 2 hours or overnight.

- First Bake (Loaf): Preheat oven to 400°F (200°C). Shape into a tight loaf. Bake on parchment 30–35 minutes until cooked. Rest 10 minutes, slice very thin.

- Vertical Setup: Thread slices onto upright metal skewer in a deep pan (use potato base if needed). Press tightly.

- Second Bake: 425°F (220°C) for 15–20 minutes until crisp. Broil 2–3 minutes for extra browning.

- Slice and Serve: Shave thin slices. Wrap in flatbread with veggies and sauce.

İmam Bayıldı: Softness Under Fire

İmam Bayıldı is simple: whole eggplants slit open and stuffed with onions cooked down until sweet, tomatoes softened into sauce, garlic mellowed, parsley folded in at the end. If done right, it is so soft, you can simply scoop it up with a fork. Its origins lie in the Ottoman domestic kitchen rather than the palace or the street. Eggplant, brought to Anatolia centuries earlier, became central to Ottoman cuisine precisely because it absorbed oil, spice, and labor.

The name, meaning “the imam fainted”, comes from folklore surrounding the history of the dish, with several possible meanings. Some say an imam fainted from delight at how delicious it was. Others say he fainted when he learned how much olive oil his wife had used to make the dish, depleting their stores. In the final version, the Imam ate so much that he slipped into a food coma. Either way, it became central to Turkish cuisine, often being served cold. While served cold, in the late 70s, it would become central to an event that saw the Turkish people under fire.

The years after the June 1970 Workers’ Resistance did not resolve the contradictions it exposed. The constitutional victory, striking down the anti-union amendments, did not stabilize the country. Instead, it sharpened lines. The 1971 military memorandum reasserted control without fully suspending civilian politics. Governments rose and fell quickly. Inflation climbed. Unemployment spread. Universities radicalized. So did the streets.

Labor did not retreat. DİSK continued to grow. So did socialist parties, student movements, and neighborhood committees. May Day, legalized and reclaimed, became the central ritual through which these forces made themselves visible. Each year it grew larger, more confident, more disciplined. It was not merely a demonstration; it was a rehearsal of power.

At the same time, the state fractured internally. Security forces competed rather than coordinated. Intelligence agencies pursued shadow wars against the left. Paramilitary groups emerged, particularly from the far right (such as the Grey Wolves), armed and protected by segments of the state apparatus. Political assassinations became routine. Bombings, drive-by shootings, and street clashes normalized fear.

This was Cold War violence, but localized.

By 1977, everyone understood that May Day would be a test. DİSK called for a mass gathering at Taksim Square in Istanbul, the symbolic heart of the republic. Half a million people came. Workers arrived in disciplined columns from factories and neighborhoods. Banners were raised. Slogans echoed off concrete and glass. Families came. Students came. The square filled not with panic but with confidence.

This mattered. After years of instability, the gathering was calm. It was orderly. It suggested that mass politics did not have to mean chaos, that the left could claim space responsibly. That suggestion was intolerable to those who benefited from disorder.

Shortly after the speeches began, gunfire erupted.

Shots came from surrounding buildings: the Intercontinental Hotel, the Water Administration building, nearby rooftops. Panic spread instantly. People ran toward exits that narrowed into bottlenecks. Police vehicles blocked escape routes. Armored cars advanced into the crowd. Tear gas compounded confusion. Some people were trampled. Others were shot. Thirty-four people died. Hundreds were injured.

No shooter was conclusively identified. No high-level perpetrators were punished.

What mattered was the effect.

The massacre shattered the illusion that legality could protect mass politics. This was not June 1970, when the army intervened openly and the courts later acknowledged wrongdoing. This was violence without authorship. Terror without fingerprints. It was a message: even peaceful strength would be met with annihilation.

In the days after May 1, mourning took place not only in streets but in homes and union halls. This is where İmam Bayıldı reenters the story.

İmam Bayıldı is often cooked in advance, served at room temperature. It is made in batches. It feeds many. In the aftermath of the massacre, people gathered quietly; after funerals, after hospital visits, after meetings conducted under surveillance. They cooked food that did not require attention at the table so they could mourn. Food that could be eaten slowly, between conversations that trailed off or stopped entirely. İmam Bayıldı being a food that gives way under a fork with no resistance, made it the perfect pairing.

After 1977, something hardened. May Day was banned again. Mass gatherings were restricted. Fear returned to the calculus of organizing. Political violence escalated further, spiraling toward the 1980 coup, which would formalize repression and dismantle organized labor for a generation.

But 1977 was the turning point in consciousness. June 1970 had taught workers they could stop the country. May 1977 taught them that stopping the country did not mean the country would stop killing them.

While presented here as a dish of mourning, it is a celebration of the tastes. Make it and enjoy.

İmam Bayıldı (Stuffed Eggplants)

Description: Tender eggplants stuffed with a rich onion–tomato mixture, baked until silky. A legendary Ottoman vegan dish.

Serves: 4

Ingredients:

Eggplants:

- 4 small eggplants

- Olive oil for frying

Filling:

- 2 large onions, sliced

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- 2 tomatoes, diced

- 1 green pepper, chopped

- ¼ cup olive oil

- 1 tbsp tomato paste

- 1 tsp sugar

- 1 tsp salt

- ½ tsp black pepper

- ¼ cup chopped parsley

- Optional: 1 tbsp pine nuts or currants

Baking:

- ½ cup hot water

- 1 tbsp olive oil

Instructions:

- Prepare Eggplants: Peel in stripes, soak in salted water 30 minutes, drain, dry. Lightly fry all sides 8 minutes. Cool and slit lengthwise.

- Make Filling: Sauté onions and garlic in olive oil 8–10 minutes. Add pepper, tomatoes, paste, sugar, salt, pepper; cook 10 minutes. Stir in parsley (and optionals).

- Stuff and Bake: Preheat oven to 350°F (180°C). Stuff eggplants, place in dish. Pour water + oil around (not over). Cover and bake 40–45 minutes.

- Serve: Warm or room temperature with bread.

Tips: Improves overnight.

Pide: Firing Up the Oven

Pide is sometimes called “Turkish Pizza”. These boat-shaped flatbreads, are topped with a variety of toppings, and cut into little rectangles. Its history predates the republic by centuries. Flatbreads baked in communal brick ovens were a constant across Anatolia, but the classic boat shape of pide emerged as a practical method of keeping the juices from meats and other toppings from spilling into the rest of the oven. It soon spread from Anatolia to the rest of the Turkish heartland, with the Black Sea region creating the most well known versions. So important did this dish become to the Turkish people, that in 1502, Sultan Bayezid II enacted laws regulating pide’s quality. In the late Ottoman period, it would become an urban bakery staple. It was truly food enjoyed by urban laborers and pastoral farmers alike. The unity of this food across classes would become important in the late 1980s.

The massacre at Taksim did not immediately end labor politics; it poisoned them. Violence escalated through 1978 and 1979. Street assassinations multiplied. Entire neighborhoods were divided along ideological lines. The state’s response oscillated between paralysis and selective brutality. By the time the military seized power on September 12, 1980, the coup was framed not as a rupture but as a grim restoration of order.

Order came at a cost. Parliament was dissolved. Political parties were banned. DİSK was shut down; its leaders were arrested and tried. Strikes were outlawed. Thousands were detained, tortured, exiled, or silenced. The new constitution of 1982 entrenched authoritarian rule and sharply restricted union activity. Labor did not merely lose visibility; it lost legality.

And yet, life continued. People still worked, commuted, taught, drove buses, loaded docks, staffed factories that now ran under emergency laws. They still ate. In this period, public political space shrank almost to nothing, but semi-public space survived. One of those spaces was the pide shop.

Pide shops were not meeting halls or union offices. They were nondescript and mundane. That was their protection. They stayed open late because workers ate late. They took cash, credit, sometimes neither. They were lit, warm, and loud enough to drown out whispered conversations. In a decade when gathering could itself be suspicious, sitting in a pide shop was still normal. It was not resistance; it was continuity.

The 1980s were not static. The junta gradually handed power to civilians, but on its own terms. Turgut Özal’s rise marked a shift from overt military rule to neoliberal restructuring. Export-led growth, privatization, wage suppression, and union containment became policy. Inflation eroded incomes. Real wages fell dramatically through the decade. Workers were disciplined not by tanks in the street, but by contracts rewritten, strikes delayed, courts stacked.

By the late 1980s, the contradiction became unbearable. The economy grew on paper, but living standards lagged. Teachers, municipal workers, miners, factory laborers, civil servants all felt the squeeze. Crucially, a generation that had been politically frozen since 1980 began to move again. They had learned caution, but not resignation.

This is where pide shifts from backdrop to actor.

The Bahar Eylemleri of 1989 did not begin as a single call to action. They emerged from hundreds of workplace-level disputes over wages, bonuses, and contracts, especially in the public sector. When legal strike mechanisms failed; blocked by arbitration, delayed by courts, workers acted anyway. They marched, slowed production, walked out, returned, walked out again. The scale surprised everyone. Over a million workers participated across more than a hundred industries.

These were not the theatrical marches of the 1970s. They were pragmatic, dispersed, relentless. Sustaining them required logistics as much as slogans. Neighborhoods organized food. Families cooked. Bakeries extended credit. Pide ovens worked overtime.

A bag of pide could sustain a picket line through the night or fuel a march that stretched longer than expected. In cities like Bursa and Kocaeli, union representatives met not in offices, still risky, but over shared bread in late-night bakeries. In Zonguldak, miners on rotating actions ate pide between shifts, between arguments about how far they could push before the state pushed back.

There is a reason workers remembered it as “the bread that kept the Spring going.”

Even bakers themselves joined in. Fırın workers staged brief shutdowns in solidarity, symbolic pauses rather than prolonged strikes, knowing exactly how fragile their position was. Others offered free or discounted pide, lahmacun, or simple cheese-topped slices to demonstrators. This mattered. It marked a return of worker to worker organizing, after years of enforced isolation.

The state responded unevenly. Police broke up some marches. Governors banned others. But the repression of 1989 did not carry the same absolute certainty as that of 1980. The regime hesitated. International scrutiny mattered more. The economy needed stability. Concessions were made. Wages rose modestly. Confidence rose more.

This confidence did not erase memory. The shadow of 1977 and 1980 remained. No one believed the state had become benign. What changed was the calculation. The Spring Actions proved that collective movement was possible again, even within constraints. It did not overturn the system, but it cracked the silence that had sealed it.

The Bahar Eylemleri did not end repression, nor did they restore the lost 1970s. But they mattered because they were collective again. They rebuilt muscle memory. They taught a new generation that organization could survive invisibly, then reappear.

By 1989, the ovens were no longer just staying lit. They were feeding something that had begun to rise.

Of the two presented here, I liked the version with egg, cheese, and sausage more. I substituted pepperoni for the sucuk. It works great!

Turkish Pide (Boat-Shaped Flatbread)

Description: Yeasted boat-shaped flatbread with optional toppings like beef or cheese/sucuk.

Serves: 4–6 pides

Ingredients:

Dough:

- 3 cups (375g) all-purpose flour

- 1 cup (240ml) warm water

- 2¼ tsp (1 packet) dry yeast

- 1½ tsp sugar

- 1½ tsp salt

- 2 tbsp olive oil (plus extra for brushing)

Option A: Beef (Kıymalı) Filling:

- 300g ground beef or lamb

- 1 small onion, finely minced

- 1 small tomato, finely diced

- 1 small green pepper, finely diced

- 1–2 tbsp tomato paste

- 1 tsp paprika

- ½ tsp cumin

- Salt & pepper

- Optional: chopped parsley

Option B: Cheese & Sucuk:

- 1 cup shredded mozzarella or kaşar cheese

- 60–80g sucuk (sub chorizo, salami, or pepperoni), thinly sliced

- 1 egg (optional, per pide)

Instructions:

- Make Dough: Bloom yeast in water with sugar 10 minutes. Add flour, salt, oil; knead 8–10 minutes. Rise 1 hour until doubled.

- Prepare Filling: Mix chosen filling ingredients (beef raw).

- Shape: Preheat oven to 475°F (245°C) with stone/sheet. Divide dough into 4–6. Roll into thin ovals. Add filling in center. Fold edges to form boat, pinch ends.

- Bake: Brush edges with oil or egg. Bake 10–12 minutes until browned.

- Finish (Optional): Brush beef with butter/parsley; add egg to cheese in last 2 minutes.

Tips: Roll dough thin for crisp edges. Serve with lemon for beef.

Ezogelin Çorbası: Warmth for the Long Walk

Ezogelin Çorbası is a soup born of scarcity and adaptation. Its legend ties it to Ezo Gelin, a young woman from southeastern Anatolia in the early twentieth century, remembered less for her biography than for what she cooked: a lentil and bulgur soup enriched with onions, tomato paste, dried mint, and chili flakes. Lentils provided protein where meat was rare; bulgur stretched the pot further; spices added warmth when fuel and calories were limited. Often compared to its lighter cousin, mercimek, ezogelin is closer to a hearty meal than a starter. It is the perfect soup for a cold day, or in the early 90s, a long, cold walk.

The Spring Actions of 1989 cracked open a decade of enforced stillness, but they did not resolve the structural pressures placed on labor since 1980. Wage gains were partial. Inflation surged. Public sector workers, briefly emboldened, discovered how quickly concessions could be clawed back. The Özal government’s neoliberal program continued: privatization accelerated, state enterprises were restructured, and unions remained constrained by laws written under military rule. The state had not forgotten how to repress; it had simply learned when to retreat and when to wait.

Nowhere were these contradictions sharper than in in the mining city of Zonguldak.

Coal mining in the Black Sea region had long been a pillar of the Turkish state. Since the early republic, coal from Zonguldak fueled industry, railways, and power plants. The mines were state-owned, dangerous, and indispensable. Miners lived with chronic injury, lung disease, and death as occupational facts. In exchange, they had once been offered stability: secure employment, housing, healthcare, and a degree of political leverage. By the late 1980s, that bargain was unraveling. Wages lagged behind inflation. Working conditions deteriorated. Privatization loomed, threatening not only jobs but entire towns built around the mines.

The Bahar Eylemleri had shown miners that collective action was again possible. In 1990, when collective bargaining negotiations between the Turkish Hard Coal Enterprises (TTK) and the miners’ union stalled, miners escalated. Strikes spread. Production slowed. The government responded with familiar tactics: legal delays, arbitration threats, and public warnings about “economic sabotage.” But Zonguldak was not a factory on the outskirts of a city. It was a region. When miners stopped, everything stopped.

By January 1991, patience collapsed into decision.

On January 4, nearly 48,000 miners and supporters began a march from Zonguldak toward the Turkish capital of Ankara; roughly 400 kilometers in winter conditions. It was an audacious move, unprecedented in scale since the early republican period. This was not a symbolic walkout or a one-day protest. It was a mass migration of labor, leaving pits, towns, and families behind to confront the state directly.

Ezogelin Çorbası moved with them.

Along the Black Sea coast and into the interior, villagers opened their homes, municipal buildings, mosques, and schools to the miners. Kitchens became logistical nodes. Large pots simmered from morning to night. Ezogelin made sense: ingredients were cheap, shelf-stable, and familiar. Lentils and bulgur could be bought in bulk. Chili and dried mint warmed bodies soaked by rain and snow. The soup could be stretched to feed hundreds without losing substance. It filled stomachs enough to keep people walking.

The march itself unfolded as a lesson in both solidarity and constraint. At every stage, miners were joined by families, local workers, and supporters. Women walked with children in tow. Elderly retirees marched part of the way. Banners were modest; slogans restrained. This was not the ideological theater of the 1970s. It was practical, disciplined, and unmistakably collective. The miners understood the stakes. They also understood the limits imposed since 1980. No one expected the state to collapse. What they demanded was recognition.

The state responded by tightening the road.

As the march approached Ankara, security forces blocked key routes. Governors issued bans. Negotiations were reopened under pressure. Behind the scenes, the government calculated risk: international optics, domestic legitimacy, and the memory, still raw, of how quickly repression could spiral. Tanks did not roll. But the road did not open either.

The march was stopped in Mengen, short of Ankara.

In conventional terms, it was a defeat. The miners did not reach the capital. Their demands were only partially met. The government avoided setting a precedent that mass marches could force policy change. But to frame the Zonguldak Miners’ March as failure misses its historical weight.

However, its significance lay in accumulation rather than spectacle.

The march proved that the confidence rebuilt in 1989 could be carried forward, literally. It showed that labor could still mobilize at scale despite legal restrictions. It revealed that communities beyond the workplace would still step in: cooking, housing, feeding, sustaining. This mattered profoundly in a post-coup society designed to isolate workers from one another. Each bowl of soup ladled along the route was a quiet refusal of that isolation.

Within months, Turkey would face new shocks. The Gulf War disrupted the economy. Inflation surged again. Özal would die in 1993, opening another political chapter. Yet the miners’ march remained a reference point. It was invoked in later labor struggles as proof that mass action had not been permanently extinguished by 1980. It stood as a bridge between the cautious rediscovery of protest in 1989 and the more confrontational labor politics that would surface in the mid-1990s.

When miners ate Ezogelin along the road, steam rising into winter air, they were not reenacting folklore. They were drawing on a practical tradition of mutual aid embedded in Anatolian life. In a country where the state had long demanded sacrifice without protection, this mattered. It reminded people that care could still flow horizontally, from kitchen to road, from village to march.

I never heard of this soup before starting the cooking for Turkish week, but I can say confidently this is my new go-to “cold day soup”.

Ezogelin Çorbası (Bride’s Lentil Soup)

Description: Comforting red lentil soup enriched with bulgur, rice, and Turkish pepper paste.

Serves: 4

Ingredients:

- 1 cup red lentils

- ¼ cup fine bulgur

- ¼ cup rice

- 1 onion, chopped

- 2 tbsp olive oil or butter

- 1 tbsp tomato paste

- 1 tbsp pepper paste (mild or hot)

- 1 tsp paprika

- 1 tsp cumin

- 1 tsp dried mint

- 6 cups vegetable or chicken stock

- Salt & black pepper

- Lemon wedges for serving

Instructions:

- Base: Sauté onion in oil until soft.

- Add Pastes: Stir in tomato and pepper pastes; cook 2–3 minutes.

- Add Grains & Spices: Add paprika, cumin, mint, then lentils, bulgur, rice, and stock.

- Simmer: 30–35 minutes until tender.

- Blend: Partially blend or leave rustic.

- Finish: Season. Serve with lemon.

Optional Garnish (Nane Yağı): Melt 1 tbsp butter, add ½ tsp pepper paste + pinch mint; drizzle over bowls..

Menemen: Mix-Up in the Square

Menemen is a simple dish elevated into something extravagant. Eggs scrambled gently into softened tomatoes and green peppers, usually with onions, sometimes without. Olive oil instead of butter. Bread for scooping. Beyond that, everything else is negotiable. Some add sausage, others insist that meat violates its spirit. Some crumble white cheese, others consider that a regional version. Even the question of onions can spark argument.That flexibility is not accidental. Menemen emerged as a modern dish alongside the spread of tomatoes and peppers into Anatolian cooking in the late Ottoman and early Republican periods.

In the 1920s, in a Turkey reshaped by migration, as orthodox Greeks fled Turkey for Greece and Muslims fled Greece for Turkey, Cretan Turks brought with them a Greek-style meat and vegetable stew. The only problem was, in a time of scarcity, meat was hard to come by, and so they made due with eggs instead. Also in the 1920s, tomatoes found their way into Turkish cooking, and the new dish found a perfect binder. The communal spirit of this dish would become crucial in 2013.

By 2013, Turkey had changed in ways the miners of Zonguldak could scarcely have imagined. The country that entered the new millennium was no longer defined primarily by state-owned heavy industry or rural labor migration. It was urban, service-oriented, and deeply unequal. After the 2001 financial crisis, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power promising stability, growth, and an end to the old secular–military tutelage. For a time, it delivered. Economic growth was real. Infrastructure expanded. Millions experienced rising living standards. But beneath that surface, a new set of tensions accumulated.

Power centralized. Independent institutions weakened. Courts were reshaped. Media ownership concentrated. Urban space itself became a site of extraction. Istanbul, especially, was remade through aggressive redevelopment: shopping malls replaced public spaces; historic neighborhoods were cleared in the name of renewal; construction became both economic engine and political symbol. Trees were not just trees. They stood in the way of profit, spectacle, and control.

Gezi Park was small, almost trivial in scale; a patch of green beside Taksim Square, itself already loaded with the memory of May Day 1977 and decades of contested public assembly. When plans were announced to demolish the park and replace it with a reconstruction of an Ottoman-era barracks housing a shopping mall, the objection was initially modest. Environmentalists camped in the park. Architects filed lawsuits. A handful of activists pitched tents.

The state’s response transformed the issue.

On May 28, 2013, police moved in with tear gas and batons, burning tents and dispersing the campers. The violence was unnecessary, disproportionate, and highly visible. Images spread instantly. What might have remained a local planning dispute detonated into a national uprising. People did not come to Gezi because they had studied zoning laws. They came because something familiar had happened again: power had spoken with force instead of listening.

Within days, Taksim Square and Gezi Park were occupied. Protests spread to dozens of cities across Turkey. Millions participated in some form, marching, banging pots from balconies, sharing information online, or simply showing up. The movement had no single leader, no unified program, and no agreed endpoint. That was both its strength and its vulnerability.

Inside the park, a different kind of order emerged. Protesters organized libraries, first-aid stations, childcare areas, and, crucially, kitchens. Food arrived from everywhere: bakeries donating bread, restaurants sending trays, individuals carrying bags of produce on the metro. Cooking became logistics, politics, and care at once. Large pans appeared on camping stoves. Someone chopped peppers. Someone else cracked eggs. Someone stirred.

Eating in the park collapsed social distance. Students, unionists, white-collar professionals, artists, football ultras, feminists, Kurds, secularists, and practicing Muslims ate from the same pans. Political identities remained, but hierarchy softened. People argued fiercely about ideology and then passed bread. The act of feeding one another did not resolve contradictions, but it suspended them long enough to coexist.

The protests themselves were chaotic and creative. Humor flourished alongside rage. Slogans mutated daily. Graffiti rewrote official language into parody. Police violence escalated: tear gas canisters fired directly at bodies, water cannons laced with chemicals, raids at dawn. Several protesters were killed. Thousands were injured. Yet the occupation persisted for weeks, not because it had seized power, but because it had seized meaning.

The state eventually reclaimed the space by force. On June 15–16, police cleared the park. Tents were destroyed. Barricades dismantled. The square was sealed. In the immediate aftermath, the government framed Gezi as a foreign-backed plot, a moral threat, a brief disturbance already resolved. In institutional terms, that framing largely prevailed. No major concessions were made. Repression intensified in the years that followed.

And yet, like the miners’ march, Gezi could not be measured solely by outcomes.

Gezi reshaped political memory. It marked the moment when a generation that had grown up after the 1980 coup discovered itself as a collective actor. It normalized protest for people who had never marched. It exposed the limits of consent under neoliberal authoritarianism. It taught skills; mutual aid, rapid organization, horizontal decision-making, that would reappear later, even under harsher conditions.

Neither overturned the state. Both altered what people believed was possible.

Menemen is almost like a shakshuka. However, instead of poaching eggs in a tomato sauce, the eggs and tomatoes and peppers all cook together, forming something creamy and wonderful.

Menemen (Turkish Scrambled Eggs)

Description: Soft, silky scrambled eggs cooked in a tomato–pepper base — a classic Turkish breakfast.

Serves: 2–3

Ingredients:

- 4 large eggs

- 2 medium tomatoes, diced (or 1 cup canned)

- 1 green pepper or sivri biber, chopped

- 1 small onion, chopped

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 1 tsp red pepper flakes (optional)

- ½ tsp salt

- ¼ tsp black pepper

- 1 tbsp chopped parsley (garnish)

- Optional: 50g feta, crumbled

Instructions:

- Cook Vegetables: Heat oil over medium. Sauté onion and pepper 5–7 minutes. Add tomatoes, flakes, salt, pepper; cook 8–10 minutes until thick.

- Add Eggs: Whisk eggs, pour in. Stir gently 2–4 minutes until just set.

- Serve: Top with parsley (and feta). Eat with bread or simit.

Tips: Adjust stirring for texture — more for creamier, less for chunkier.

Comments

Post a Comment