Samoa: Coconuts and Courage

Samoa: Coconut and Courage

In 1961, the Western Samoa Act passed by New Zealand designated the tiny island nation of Samoa (Then called Western Samoa) as the first independent nation in Oceania outside of Australia and New Zealand. But independence was not granted with the stroke of a pen. It was earned over the course of decades through struggle, sacrifice, and solidarity.

For centuries, these islands have stood as a cradle of Polynesian culture. Before the arrival of Europeans, Samoa was governed by a complex system of chiefly titles, village councils (fono), and kinship networks that emphasized service, humility, and balance. It was a world bound by coconut palms, breadfruit groves, and the rhythm of the Pacific Ocean, where power was measured not by conquest, but by one’s ability to provide and care for others. This way of life is called fa’a Samoa, “The Samoan way”.

European ships arrived in the early 18th century, first traders, then missionaries, and finally colonizers. By the late 19th century, Samoa became a pawn in the imperial rivalries of Germany, Britain, and the United States, culminating in two brutal civil wars where factions sponsored by each of these imperial powers would fight for the title of King. The 1899 Tripartite Convention carved the islands apart, the western islands (modern Samoa) falling under German control, while the eastern islands (American Samoa) went to the United States. German rule brought plantations and taxes, forcing Samoans into a cash economy that clashed with communal life. Chiefs who resisted were exiled; others, co-opted. But beneath the quiet obedience of coconut groves, the seeds of resistance were taking root.

In 1908, the Mau a Pule rebellion erupted on Savai‘i, led by Lauaki Namulau‘ulu Mamoe, who defied German demands for tribute and obedience. His followers, farmers, fishermen, and orators, rejected foreign interference and insisted on the right to self-governance. Though Lauaki was exiled and later died on the journey home, the rebellion became the first spark of Samoa’s long struggle for independence. Around village fires and in communal feasts, the people reaffirmed their unity through food, simple dishes like Fa‘alifu Fa‘i, green bananas boiled in coconut cream, sustaining the rebels as they dreamed of freedom.

When New Zealand took control during World War I, Samoa’s suffering did not end. In 1918, New Zealand administrators allowed an influenza-infected ship to dock in Apia, unleashing a pandemic that wiped out over 20% of the Samoan population in just weeks. Entire villages were left silent. In grief and anger, families gathered around their umu (earth ovens), cooking Palusami, taro leaves baked in coconut cream. Each bite was a prayer for survival amidst the forces of extinction.

Out of tragedy rose the Mau movement of the 1920s, a nonviolent, nationwide campaign for self-determination. The Mau rejected violence, choosing peaceful marches, petitions, and civic disobedience. Its members dressed in fine white, the color of peace, and organized through the same village networks that had sustained Samoa for centuries. Oka I‘a, a dish of raw fish marinated in coconut cream and citrus, became the food of gatherings, shared communally after long days of protest meetings beneath the palms. The Mau united Samoans of all classes, and even members of the Chinese-Samoan community who joined in solidarity, making it one of the first truly Pacific independence movements.

Then came Black Saturday, December 28, 1929. A peaceful march in Apia turned deadly when New Zealand police opened fire on unarmed Samoan demonstrators, killing several, including the movement’s leader, Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III, who died calling for peace even as bullets fell. In the days after, families across the islands cooked Sapasui, Samoan-style chop suey, made from imported noodles, soy sauce, and corned beef, a dish born of colonial trade but reclaimed as their own. It fed the mourning, its mingled flavors reflecting Samoa itself: Pacific ingredients, Asian influence, but distinctly Samoan all the same.

The struggle continued into the 1930s, when Samoan women stepped forward to lead after the imprisonment and exile of many male leaders. Known as the Women’s Mau, they used traditional weaving circles and church groups to organize protests, boycott colonial goods, and sustain the movement through song and solidarity. Pani Popo, soft buns baked in sweet coconut milk, became a staple of these gatherings, comfort in a time of loss, sweetness amid struggle. Their persistence ensured the flame of independence would not die, even under constant surveillance and suppression.

By the mid-20th century, Samoa stood tall as the first Pacific nation to regain independence, not through war, but through unity, patience, and faith in the ways of Samoa.

Samoan cuisine is rich in coconut, taro, and the fruits of the sea. It also carries with it the story of a long resistance.

Today, we remember that story not through monuments, but through five humble dishes; the everyday meals that nourished a revolution. Fa‘alifu Fa‘i fueled the Mau a Pule uprising of 1908. Palusami sustained communities through the 1918 influenza tragedy. Oka I‘a brought together the organizers of the Mau movement of the 1920s. Sapasui fed the mourners after Black Saturday in 1929. And Pani Popo, sweet with coconut milk, comforted the Women’s Mau in the 1930s.

So light the umu. Today we not only eat, but remember the unbroken spirit of an ocean people and fa’a Samoa.

Fa’alifu F’ai: Bananas Rebellion

Fa’alifu F’ai, or green bananas, or plantains simmered in rich coconut cream, is a cornerstone of Samoan cuisine. It features chunks of ripe or green bananas boiled until tender, then bathed in creamy coconut milk, often flavored with a touch of salt, onion, or seawater for that subtle oceanic tang. This staple traces its roots deep into Polynesian history, predating European contact by centuries. Banana plants, brought to the Pacific by ancient voyagers from Southeast Asia around 3,000 years ago, became integral to the Samoan diet. The dish's simplicity, harvested from backyard groves, prepared over open fires or in umu (earth ovens), reflects the self-reliant, communal ethos of fa'a Samoa, the traditional Samoan way of life. Variations abound: some add young taro leaves for a palusami twist, others keep it pure to highlight the banana's soft, starchy texture absorbing the coconut's velvety richness. It's a meal for everyday consumption, served at family feasts on Sundays or ceremonial events, symbolizing the harvest and the unbreakable bond between Samoans and their soil. In the early 20th century, as colonial forces encroached, this humble dish became more than food, it embodied the Samoan way of life under threat.

The story of Fa’alifu F’ai intertwines with the dawn of Samoa's organized resistance to colonialism, particularly the Mau a Pule of 1908, the spark that ignited a decades-long flame for independence. To understand this tie, we must delve into the dense history of Samoa under German rule. By the late 19th century, Samoa's strategic Pacific location had drawn the imperial ambitions of Germany, Britain, and the United States. The 1899 Tripartite Convention carved up the islands: the eastern group went to America (now American Samoa), while the western islands, including Upolu and Savai'i, became German Samoa. Wilhelm Solf, appointed Governor in 1900, arrived with a vision of "enlightened" colonialism. A former diplomat with a doctorate in Sanskrit, Solf was seen as liberal compared to his peers; he spoke some Samoan, incorporated elements of fa'a Samoa into administration, and focused on economic development through plantations, roads, schools, and hospitals. Yet, his policies masked a deeper agenda: centralizing power in Apia, the capital, and dismantling traditional Samoan structures to facilitate German control.

Solf's reforms clashed head-on with the matai system, where chiefs (matai) and orators (tulafale) held authority through consensus in villages and districts. He abolished the traditional kingship in 1900, replacing it with a puppet ali'i sili (high chief) under German oversight, and imposed taxes on copra (dried coconut), Samoa's economic lifeblood. Land alienation accelerated as German firms like the Deutsche Handels- und Plantagen-Gesellschaft (DHPG) seized vast tracts for plantations, displacing families and eroding communal land tenure. By 1908, tensions boiled over on Savai'i, the largest island, where the traditional districts of Tumua (Upolu) and Pule (Savai'i) represented the heart of Samoan governance. The catalyst was a dispute over the Oloa Company, a native-owned copra trading firm that challenged German monopolies. Solf viewed it as a threat to economic order and dissolved it, igniting widespread discontent.

Enter Lauaki Namulau'ulu Mamoe, the paramount orator from Safotulafai on Savai'i. A master tulafale known for his eloquence and strategic mind, Lauaki had been deposed by Solf earlier for defying colonial edicts but retained immense influence. He rallied the matai of Pule districts, forming the Mau a Pule, "Mau" meaning firm opinion or resolute stance, and "a Pule" denoting the authority of Savai'i's chiefs. This was no armed revolt but a sophisticated, non-violent protest rooted in fa'a Samoa: petitions, boycotts of German taxes, and refusal to labor on plantations. Lauaki's followers gathered in fale (open houses), sharing Fa’alifu F’ai from communal pots, the dish's sweet-savory flavors fueling discussions on sovereignty. Bananas, harvested from ancestral groves, symbolized the very 'ele'ele that Solf's policies threatened to commodify. As families tended banana plants amid rising tensions, the meal became an act of resistance.

The movement spread rapidly across Savai'i in late 1908, with thousands withholding copra and ignoring colonial decrees. Solf, alarmed, summoned German warships, the cruiser SMS Arcona and others, to Apia harbor as a show of force. He labeled the Mau a Pule as sedition, accusing Lauaki of plotting rebellion. In early 1909, under the guise of peace talks, Solf invited Lauaki aboard the German ship SMS Condor. It was a trap: Lauaki and nine other leaders were arrested, their canoes seized to prevent escape. Solf exiled them to Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands, a distant German possession, along with their families, 71 people in total. The deportation was a brutal crackdown, marking the first major suppression of Samoan resistance. En route and in exile, many suffered from disease and hardship; Lauaki himself died at sea in 1915 while being repatriated after New Zealand seized Samoa at the outbreak of World War I. The Mau a Pule's suppression scattered its leaders but didn't extinguish the spirit. Villages continued to prepare Fa’alifu F’ai in umu pits, tying the dish to memories of lost chiefs and stolen independence.

Today, Fa’alifu F’ai remains a daily staple. In modern Samoa, it's served at independence celebrations.

For my own part, I used green plantains, and found the substitution to work quite well.

Fa’alifu Fa’i

Fa’alifu fa’i is a simple Samoan side dish featuring green bananas cooked in a savory coconut sauce. It's starchy rather than sweet, making it a great accompaniment to meats or other mains.

Ingredients (serves 4):

- 8-10 green bananas (unripe, firm ones)

- 1 can (13.5 oz) coconut milk

- 1 small onion, finely chopped (optional)

- Salt to taste

- Water for boiling

Instructions:

- Peel the green bananas carefully (they can be sticky; use gloves if needed). Cut off the ends but leave them whole or slice into large chunks if preferred.

- Place the bananas in a pot and cover with water. Add a pinch of salt and bring to a boil.

- Simmer for 15-20 minutes until the bananas are tender but not mushy. They should float to the top when ready.

- Drain most of the water, leaving a little in the pot.

- Pour in the coconut milk and add the chopped onion if using. Stir gently and heat on low for 5-10 minutes to infuse flavors. Do not boil vigorously to avoid curdling.

- If the sauce is too thin, mix 1-2 tablespoons of cornstarch with water and stir in to thicken.

- Season with more salt if needed and serve warm alongside proteins like fish or chicken.

Palusami: Leaves of Sorrow

Palusami is a beloved staple of Samoan cuisine. At its core, it consists of young taro leaves (lu'au) layered and wrapped around a filling of thick, creamy coconut milk, often enhanced with onions, salt, or seawater for flavor. Traditionally, these parcels are baked slowly in an umu, an underground earth oven heated by hot stones. Variations abound across the Pacific: in Samoa, it might include corned beef (a post-colonial addition), fish, or even just the pure vegetarian form; in Fiji, it's similar but sometimes spiced differently; and in Hawaii, it's known as laulau, often stuffed with pork. The dish's origins trace back to ancient Polynesian voyagers who brought taro and coconut from Southeast Asia around 3,000 years ago, adapting them to island life. Palusami's name is thought to derive from Samoan words meaning "to mix with seawater," reflecting its ties to the ocean and land. Served at feasts, funerals, or daily meals, it's a symbol of fa’a Samoa, the Samoan Way. In the early 20th century, amid colonial upheaval, palusami became more than food; it represented survival when external powers faltered.

The 1918 influenza epidemic in Samoa stands as one of history's most devastating colonial failures, a catastrophe that decimated Western Samoa under New Zealand's young colonial administration and sowed seeds of enduring resistance. In order to understand why, we must rewind to the geopolitical shifts that set the stage. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, New Zealand forces, acting on British orders, seized German Samoa without resistance, occupying the western islands including Upolu and Savai'i. This marked the end of 14 years of German rule, but the transition was marred by incompetence. Colonel Robert Logan, a military administrator with no prior experience in tropical governance or public health, was appointed to oversee the territory. Logan's regime prioritized military order over welfare, imposing strict controls on Samoan customs while neglecting infrastructure and health systems. By 1918, as the global Spanish flu pandemic raged, killing an estimated 50 million worldwide, New Zealand itself was reeling, with over 9,000 deaths in late 1918. Despite this, no warnings were sent to Pacific dependencies.

The flu arrived on November 7, 1918, aboard the SS Talune, a Union Steam Ship Company vessel from Auckland. The ship had departed New Zealand amid the epidemic's peak, carrying passengers and crew already exhibiting symptoms; coughs, fevers, and pneumonia. In Auckland, health checks were cursory; no quarantine was enforced despite known risks. The Talune first stopped in Fiji and Tonga, seeding outbreaks there before docking in Apia, Samoa's capital. Logan, informed of illnesses aboard, allowed disembarkation without isolation, citing a lack of medical staff and facilities. Within days, the virus exploded across the islands. Samoa's population of about 38,000 was highly vulnerable: dense villages, communal living in open fale houses, and no prior exposure to this strain amplified transmission. Symptoms were brutal; high fevers, hemorrhaging, and rapid death from pneumonia. Entire families perished; bodies piled up unburied as survivors weakened. In contrast, American Samoa, just 80 kilometers east and under U.S. Navy control, enforced a strict quarantine under Commander John Martin Poyer. No ships were allowed to land, and the territory escaped unscathed, with zero deaths; a stark testament to preventive action.

The toll in Western Samoa was apocalyptic: approximately 8,500 died, or 22% of the population, one of the highest mortality rates globally. Villages were decimated; matai (chiefs) and orators fell, disrupting social structures. Logan's response was disastrously inept: he rejected aid offers from American Samoa, including doctors and nurses, due to pride or fear of U.S. encroachment. Instead, he relied on untrained New Zealand soldiers and missionaries, who spread misinformation and failed to distribute supplies effectively. A makeshift vaccine from the Australian navy ship HMAS Encounter arrived too late and proved ineffective. Amid the chaos, Samoans turned inward, isolating in family 'aiga (extended kin groups) and relying on traditional remedies like herbal teas and rest. Palusami, prepared from abundant taro and coconuts, became a lifeline, its nutrient-rich coconut cream providing calories and hydration when imported goods vanished. Families huddled in fale, wrapping leaves in the umu as a ritual of normalcy, the sealed bundles mirroring their enforced isolation. The dish's slow cooking evoked the quiet endurance required, sustaining bodies while colonial promises crumbled.

Grief morphed into fury. Survivors blamed Logan's negligence, viewing it as deliberate indifference rooted in racism; Samoans as expendable under white rule. Petitions flooded New Zealand, demanding accountability; a 1919 Royal Commission confirmed administrative failures but offered scant justice. This betrayal reignited smoldering resentments from the earlier Mau a Pule (1908-1909) under German rule, where chiefs like Lauaki Namulau'ulu Mamoe resisted centralization. By the mid-1920s, Samoan attitudes towards independence heated up like an umu baking a palusami parcel.

Today, palusami remains a central dish in Samoan cuisine, both for its sustenance and the ritualistic communal preparation it provides. Next time I make it, I am planning on constructing an umu of my own.

Palusami

Palusami is a traditional Samoan dish made from taro leaves filled with a coconut cream mixture, often including corned beef for added flavor. It's typically baked or steamed in an underground oven (umu), but you can use a conventional oven.

Ingredients (serves 4-6):

- 12-15 young taro leaves (or spinach as a substitute if taro leaves are unavailable)

- 1 can (12 oz) corned beef, broken into pieces

- 1 large onion, finely chopped

- 2-3 garlic cloves, minced

- 2 cans (13.5 oz each) coconut cream or milk

- Salt and pepper to taste

- Aluminum foil (for wrapping if baking)

Instructions:

- Preheat your oven to 350°F (175°C) if baking.

- In a bowl, mix the corned beef, chopped onion, minced garlic, salt, pepper, and one can of coconut cream until well combined.

- Wash the taro leaves thoroughly. If using large leaves, trim the stems and veins to make them flexible.

- Layer 2-3 taro leaves together on a piece of aluminum foil. Spoon 2-3 tablespoons of the corned beef mixture into the center.

- Fold the leaves over the filling to form a parcel, then wrap tightly in foil.

- Repeat with the remaining leaves and mixture.

- Place the parcels in a baking dish and pour the second can of coconut cream over them.

- Bake for 45-60 minutes, or until the leaves are tender. Alternatively, steam for about 1 hour.

- Serve hot as a side dish with rice or taro.

Oka I’a: Raw Resolve

Oka I’a is a vibrant raw fish salad central to Samoan cuisine. Known as "oka" meaning raw or fresh in Samoan, and "i’a" for fish, this dish features cubes of fresh tuna, snapper, or other firm white fish marinated in lime or lemon juice to "cook" through acidification, then mixed with creamy coconut milk, diced cucumbers, tomatoes, onions, and sometimes chilies or spring onions for a zesty kick. Its origins trace back to ancient Polynesian seafarers who relied on ocean harvests and coconut palms, with similar preparations across Oceania: Tongan 'ota 'ika, Tahitian poisson cru, Fijian kokoda, and Hawaiian poke. Variations abound. Some add coriander, parsley, or even pineapple for sweetness, while purists keep it simple to highlight the fish's freshness. No fire or imported tools are needed; it's prepared spontaneously with a knife, bowl, and local ingredients, making it ideal for communal gatherings, feasts, or quick meals. In Samoa, it's often served chilled as an appetizer or main, symbolizing fa'a Samoa, the traditional way of life tied to sea and soil. During the turbulent 1920s, as colonial pressures mounted, Oka I’a transcended its role as a foodstuff, becoming a emblem of self-sufficiency amid economic defiance.

The Mau Movement's general strike and boycotts in the mid-1920s represent a pinnacle of non-violent resistance in Samoa's colonial history, a grassroots uprising against New Zealand's heavy-handed rule that paralyzed the administration and foreshadowed independence. Building on earlier grievances from the 1918 influenza disaster, which killed 22% of the population due to NZ negligence, and the suppressed Mau a Pule of 1908-1909 under German rule, the Mau ("firm opinion") coalesced around 1926. New Zealand had administered Western Samoa as a League of Nations mandate since seizing it from Germany in 1914, but governance was marred by cultural insensitivity. Major-General George Spafford Richardson, appointed Administrator in 1923, embodied this: a decorated military man with experience in Egypt and World War I, he viewed Samoans as "childlike" and sought to impose "progress" through taxes, land reforms favoring Europeans, and dismantling matai (chiefly) authority. Richardson banned traditional gatherings, enforced copra production for export, and marginalized mixed-race "afakasi" like Olaf Frederick Nelson, a prominent merchant of Swedish-Samoan descent who became the Mau's de facto leader.

By 1926, discontent erupted into organized action. Nelson's Citizens' Committee, formed to petition for reforms, evolved into the Mau after Richardson dismissed their demands for self-governance. Adopting the slogan "Samoa mo Samoa" (Samoa for Samoans), the movement drew inspiration from Gandhi's non-violence, with members wearing distinctive lava-lava uniforms in navy blue with white stripes. The core tactics were economic sabotage: a general strike refusing plantation labor, boycotts of imported goods from NZ traders, and withholding copra and cocoa harvests, Samoa's economic backbone, accounting for 90% of exports. Villages ceased paying head taxes, crippling revenue. This "silent strike" created a parallel shadow government: Mau committees in every district enforced local rule, collecting their own "taxes" for community needs, while ignoring colonial courts and officials. Richardson, alarmed, proclaimed the Mau seditious in 1927, deporting Nelson and two other afakasi leaders to New Zealand for six months, hoping to decapitate the movement. Instead, it grew: women's branches, led by figures like Rosabel Nelson, organized marches and sustained families through communal support.

Amid this, Oka I’a mirrored the Mau's ethos of self-reliance. As boycotts shunned kerosene stoves, canned goods, and imported fabrics, families turned to the ocean and palms, fishing with handmade lines for i’a, grating coconuts for cream, preparing Oka I’a as a quick, fuel-free meal that sustained strikers without engaging the colonial market.

In village fale (open houses), where Mau strategies were debated, bowls of marinated fish fueled resolve, its fresh tang a reminder of Samoa's pre-colonial abundance. The dish's spontaneity echoed the movement's grassroots surge: no elaborate planning needed, just local resources to defy economic dependence.

Richardson's response escalated tensions. In 1928, he requested naval support; cruisers HMS Dunedin and Diomede arrived, their marines raiding Mau headquarters and arresting hundreds. Nelson, upon return, was exiled again in 1928 for five years, but the Mau persisted, with paramount chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III assuming leadership. By 1929, 90% of Samoans supported the Mau, boycotts halving copra exports and bankrupting traders. The New Zealand colonial authority would need to either escalate or accede to the protestors demands.

As for Oka I’a it remains a testament to the Samoan way. It is quite interesting how despite having almost all the same ingredients as ceviche, the coconut milk and chili powder change the taste substantially.

Oka I'a

Oka i'a is a fresh Samoan raw fish salad, akin to ceviche but enriched with coconut milk. The acid from citrus "cooks" the fish, making it safe and flavorful.

Ingredients (serves 4):

- 1 lb fresh firm white fish (like tuna, snapper, or mahi-mahi), cubed into bite-sized pieces

- 1 cup fresh lime or lemon juice (enough to cover the fish)

- 1 can (13.5 oz) coconut milk

- 1 small red onion, finely diced

- 1-2 tomatoes, diced

- 1 cucumber, peeled and diced

- 1/2 cup fresh cilantro or green onions, chopped (optional)

- Salt to taste

Instructions:

- Place the cubed fish in a non-reactive bowl. Pour over the lime/lemon juice to fully submerge. Stir to coat and refrigerate for 30-60 minutes until the fish turns opaque (it's "cooked" by the acid).

- Drain most of the citrus juice, leaving a little for flavor.

- Add the diced onion, tomatoes, cucumber, and cilantro/green onions if using.

- Pour in the coconut milk and stir gently to combine. Season with salt.

- Refrigerate for another 10-15 minutes to let flavors meld.

- Serve chilled as an appetizer or light meal, perhaps with taro chips or rice.

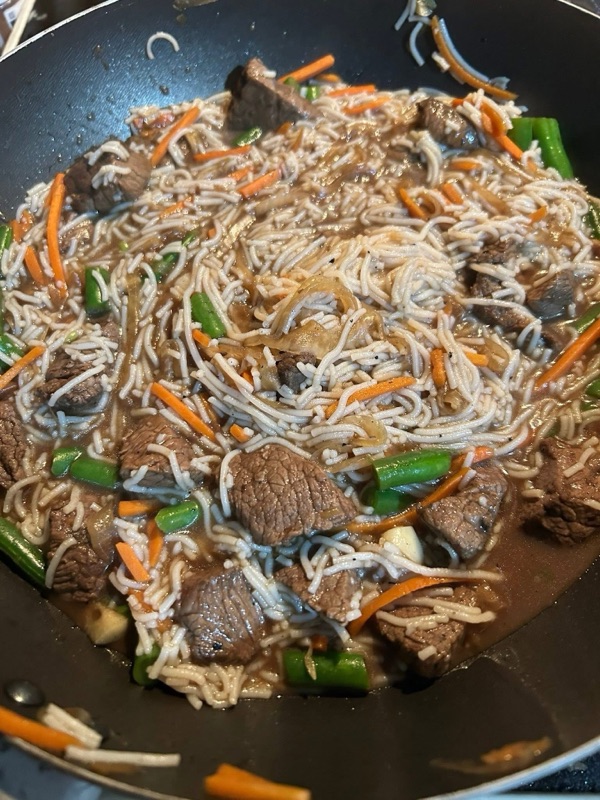

Sapasui: Noodles of Defiance

Sapasui, Samoa's take on chop suey, is a hearty stir-fry that fuses vermicelli noodles with meat, often beef, pork, or chicken, vegetables like carrots, cabbage, onions, and sometimes corn or beans, all bound in a savory soy sauce gravy. This dish, known as "Samoan chop suey," traces its roots to Chinese immigrants who arrived in the Pacific in the 19th century. Chop suey itself originated as a Cantonese-American adaptation in the mid-1800s, meaning "miscellaneous pieces," but in Samoa, it was indigenized by Chinese laborers brought as indentured workers from the 1870s onward, or earlier free settlers around 1840. These migrants, escaping poverty or seeking opportunity, introduced rice noodles and stir-frying techniques, blending them with local ingredients. Variations include adding ginger, garlic, or even coconut milk for a Polynesian twist, making it a staple at family gatherings, to'ona'i (Sunday lunches), and fa'alavelave (ceremonial events). Affordable and quick to prepare, sapasui symbolizes cultural fusion, imported noodles meeting island flavors, reflecting Samoa's history of migration and adaptation. In the 1920s, as urban centers like Apia grew with diverse populations, this dish nourished a melting pot of Samoans, Europeans, and mixed-heritage "afakasi," embodying the inclusivity that fueled resistance movements.

Black Saturday, December 28, 1929, marks a tragic zenith in Samoa's Mau movement, a non-violent campaign for independence from New Zealand's colonial rule that exposed the brutality of imperialism. The Mau, "firm opinion" in Samoan, emerged from deep-seated grievances dating back to New Zealand's 1914 seizure of Western Samoa from Germany during World War I. Administered as a League of Nations mandate, NZ's governance under figures like Colonel Robert Logan and later Major-General George Spafford Richardson was paternalistic and oppressive. By the mid-1920s, Richardson's policies, high taxes, land alienation favoring Europeans, bans on traditional customs, and marginalization of matai (chiefs), fueled the Mau's rise. Led by Olaf Frederick Nelson, a wealthy afakasi merchant of Swedish-Samoan descent, the movement adopted Gandhi-inspired tactics: boycotts of taxes and imports, strikes on copra plantations, and parallel governance in villages. Supporters wore uniforms of lava-lava skirts with white shirts and ties, chanting "Samoa mo Samoa" (Samoa for Samoans). By 1927, 90% of Samoans backed the Mau, crippling the economy.

Richardson responded with repression: declaring the Mau seditious, deporting Nelson and other leaders to New Zealand in 1927 and again in 1928, and deploying marines from cruisers like HMS Dunedin to raid Mau headquarters. Women's branches, organized by figures like Rosabel Nelson (Olaf's wife), sustained the effort through communal support. In late 1929, with exiled leaders like Nelson, Edwin Gurr, and Alfred Smyth returning aboard the Maui Pomare, excitement peaked. On December 28, a procession of about 400 Mau supporters, chiefs, women, afakasi, and even some Europeans, marched through Apia to welcome them at the wharf, as street vendors sold sapasui in stalls in the streets. The crowd, diverse in ethnicity and class, reflected Samoa's blended society. Tensions escalated when a scuffle broke out: a European constable assaulted a Mau member, prompting stones to be thrown. NZ military police, armed with rifles and a Lewis machine gun, opened fire on the unarmed crowd from the police station balcony. Eleven Samoans died, including paramount chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III, shot in the back while urging peace. His final words, "My blood has been spilt for Samoa. I am proud to give it. Do not dream of avenging it, as it was spilt in maintaining peace", echoed the Mau's non-violent ethos. Fifty others were wounded in the chaos, with police pursuing fleeing protesters into alleyways.

Sapasui's ties to Black Saturday weave through themes of cultural blending and unified resistance. As a dish born from Chinese migration and adapted in urban Apia, where diverse communities intermingled, it mirrored the Mau's inclusive coalition. Nelson, an afakasi like many urban dwellers, drew support from Europeans, Chinese traders, and indigenous Samoans, much as sapasui combined imported soy sauce and noodles with local meats and veggies. On that fateful day, marchers shared sapasui in Apia's markets or homes, its high-energy mix fueling the long procession. The dish's affordability and portability suited the mobile, grassroots nature of the protest.

The resolution of Black Saturday transformed tragedy into a catalyst for change. Global outrage ensued: newspapers condemned NZ's actions, and petitions to the League of Nations highlighted the massacre. Richardson resigned in early 1930, replaced by more conciliatory administrators. The Mau persisted with boycotts, though arrests and raids continued until 1933. A 1935 NZ Labour government election brought reforms: pardons for leaders, recognition of matai authority, and eased taxes.

New Zealand's 2002 apology by Prime Minister Helen Clark acknowledged the wrongs, including Black Saturday. Today, the event is commemorated annually, with Tamasese a national martyr. Sapasui endures as a festive staple, its blended flavors evoking the unity that overcame division.

If you like stir fries. This is DEFINITELY one you have to try.

Sapasui

Sapasui is Samoa's version of chop suey, a stir-fried noodle dish with vermicelli, meat, and vegetables influenced by Chinese cuisine. It's hearty and customizable with whatever veggies you have.

Ingredients (serves 4-6):

- 8 oz vermicelli noodles (glass noodles)

- 1 lb beef (chuck, rump, or sirloin), thinly sliced (or substitute chicken or pork)

- 2 tablespoons vegetable oil

- 1 large onion, sliced

- 3 garlic cloves, minced

- 1 tablespoon fresh ginger, grated

- 2-3 carrots, julienned

- 1 cup green beans or cabbage, chopped

- 1/4 cup soy sauce

- 2 cups water or beef broth

- Salt and pepper to taste

Instructions:

- Soak the vermicelli noodles in hot water for 10-15 minutes until soft, then drain and cut into shorter lengths if needed.

- Heat oil in a large wok or pan over medium-high heat. Add the sliced beef and stir-fry until browned, about 5 minutes. Remove and set aside.

- In the same pan, sauté the onion, garlic, and ginger until fragrant, about 2 minutes.

- Add the carrots and green beans (or other veggies), stir-frying for 3-4 minutes until slightly tender.

- Return the beef to the pan. Pour in the soy sauce and water/broth. Bring to a simmer and cook for 10 minutes to develop flavors.

- Add the softened noodles, tossing everything together. Cook for another 5 minutes until the noodles absorb the sauce and are heated through.

- Season with salt and pepper. Serve hot as a main dish.

Pani Popo: Buns of Endurance

Pani Popo, the irresistible Samoan coconut buns, are soft, fluffy yeast rolls baked in a bath of sweet, creamy coconut sauce that soaks into every bite, creating a gooey, indulgent treat. "Pani" derives from the English "bun," and "popo" from "coconut," reflecting its hybrid origins. The dish likely emerged in the late 19th century, influenced by European bakeries introduced during German colonial rule from 1900 to 1914, with similarities to German dampfnudel, steamed buns in a milky sauce. Samoan adaptations replaced milk with abundant coconut cream, sweetened with sugar, and baked in tins over open fires or in modern ovens. Traditional recipes involve kneading flour, yeast, sugar, salt, and butter into dough, letting it rise, shaping into balls, then pouring a mixture of coconut milk, water, and sugar over them before baking until golden and saturated. Variations include adding condensed milk or cornstarch for thickness, or using store-bought rolls for shortcuts. Served warm at family to'ona'i (Sunday feasts), fa'alavelave (ceremonies), or casual gatherings, pani popo symbolizes communal warmth and nurturing, often prepared by women in village settings. In the 1930s, amid colonial strife, this labor-intensive dish embodied the patient, sustaining role of Samoan women in resistance.

The 1930s Women's Mau, known as O le Faletua ma le Ta'imua (the Wives and Leaders), represented a pivotal escalation in Samoa's non-violent struggle for independence from New Zealand's mandate rule, stepping into the forefront when male leaders were suppressed. The broader Mau movement, "Mau" meaning firm resolve, originated in the 1920s, building on earlier resistances like the 1908-1909 Mau a Pule against German centralization and the catastrophic 1918 influenza epidemic under NZ negligence, which killed 22% of the population. By 1926, under Administrator Major-General George Spafford Richardson's oppressive policies, high taxes, land grabs for Europeans, bans on customs, and deportation of leaders like Olaf Frederick Nelson, the Mau organized boycotts, strikes, and parallel governance. The movement's slogan, "Samoa mo Samoa," unified 90% of Samoans by 1929, with supporters in distinctive uniforms engaging in passive resistance.

The turning point was Black Saturday, December 28, 1929, when NZ police fired on a peaceful Apia procession, killing 11, including paramount chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III. His martyrdom galvanized the Mau, but reprisals followed: hundreds arrested, men fled to the bush or were imprisoned, leaving villages vulnerable. Into this void stepped the Women's Mau, formalized in early 1930 as O le Faletua ma le Ta'imua. Led by figures like Rosabel Nelson (Olaf's wife), Fa'afetai Tamasese (Tamasese's widow), and others from matai families, it swelled to over 8,000 members by mid-1930. Drawing from traditional roles as faletua (chiefs' wives) and ta'imua (leaders' supporters), women leveraged their status as peacekeepers and organizers in fa'a Samoa, the communal way of life. They wore Mau uniforms, held banned public meetings, sang protest songs, and defied curfews, often in Apia under armed guard.

Their activities were multifaceted: fundraising through dances and sales to support exiled leaders, smuggling messages and supplies to men in hiding, and sustaining boycotts by managing village economies. In 1930, they petitioned the League of Nations and gained international backing from the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Colonial reluctance to brutalize women, rooted in cultural norms and fear of backlash, allowed them greater mobility than men. Yet, repression came: arrests, fines, and forced labor for some, though less severe than for males. By 1931-1932, as NZ replaced Richardson with Brigadier-General Herbert Hart, who eased some policies, the Women's Mau persisted, organizing marches and maintaining morale amid economic hardship. Their efforts bridged the Mau's survival into the mid-1930s, influencing global opinion and NZ politics.

Pani Popo's connections to the Women's Mau run deep. In villages, women prepared pani popo for secret gatherings, its sweet aroma fostering community bonds while they plotted strategies or fundraised.

The buns' communal sharing at fa'alavelave echoed how faletua mobilized 'aiga (extended families) networks, providing sustenance to fugitives in the bush or imprisoned kin. Coconut, a local staple, represented self-reliance against colonial imports, much as women upheld fa'a Samoa amid boycotts. Even in urban Apia, where mixed-heritage women like Rosabel operated, pani popo blended traditions, fueling diverse allies in protests.

The Women's Mau's resolution marked a gradual victory, reshaping Samoa's path to freedom. By 1933, persistent non-cooperation and international pressure forced NZ concessions: reduced taxes, recognition of matai authority, and return of exiles like Nelson in 1933. The 1935 election of NZ's Labour government under Michael Savage brought further reforms, pardoning Mau leaders and easing mandates. Though the Mau dissolved formally in 1936, its legacy endured through World War II and UN trusteeship, culminating in independence on January 1, 1962, the first Pacific nation to achieve it. Women like those in O le Faletua ma le Ta'imua were hailed as peace warriors, their roles integral to national identity. Today, pani popo graces independence celebrations, a sweet reminder of endurance.

If you like Hawaiian buns, you definitely will want to try this. It is like the softer, more coconutty cousin.

Pani Popo (Samoan Coconut Buns)

Servings: about 12 rolls

Ingredients

For the dough:

- 4 cups all-purpose flour

- 2 ¼ tsp active dry yeast (1 packet)

- ¼ cup sugar

- 1 tsp salt

- 3 Tbsp butter, melted

- 1 large egg

- 1 cup warm water (105–110°F / 40–43°C)

- ½ cup coconut milk

For the coconut sauce:

- 1 can (13.5 oz / 400ml) coconut milk

- ½ cup sugar (adjust to taste — some recipes go lighter)

- ½ cup water

Instructions

- Activate the yeast

- In a bowl, combine warm water, 1 Tbsp of the sugar, and the yeast. Let sit 5–10 minutes until foamy.

- Make the dough

- In a large mixing bowl (or stand mixer with dough hook), combine flour, sugar, and salt.

- Add yeast mixture, egg, melted butter, and coconut milk. Mix until dough forms.

- Knead for 8–10 minutes (or 5–6 in mixer) until smooth and elastic.

- First rise

- Place dough in a greased bowl, cover, and let rise in a warm place 1–1.5 hours, until doubled.

- Shape the rolls

- Punch down the dough, divide into 12 equal pieces, and shape into smooth balls.

- Arrange in a greased 9×13-inch baking dish.

- Second rise

- Cover and let rolls rise 30–45 minutes until puffy.

- Make the coconut sauce

- Whisk coconut milk, sugar, and water together until sugar dissolves.

- Bake with coconut milk

- Pour sauce evenly over risen rolls (they should be partially sitting in the sauce).

- Bake at 350°F (175°C) for 30–40 minutes, until golden brown on top and sauce has thickened slightly at the bottom.

- Cool & serve

- Let rest 10 minutes before serving. Rolls will be fluffy, slightly sweet, and sitting in creamy coconut sauce.

Comments

Post a Comment