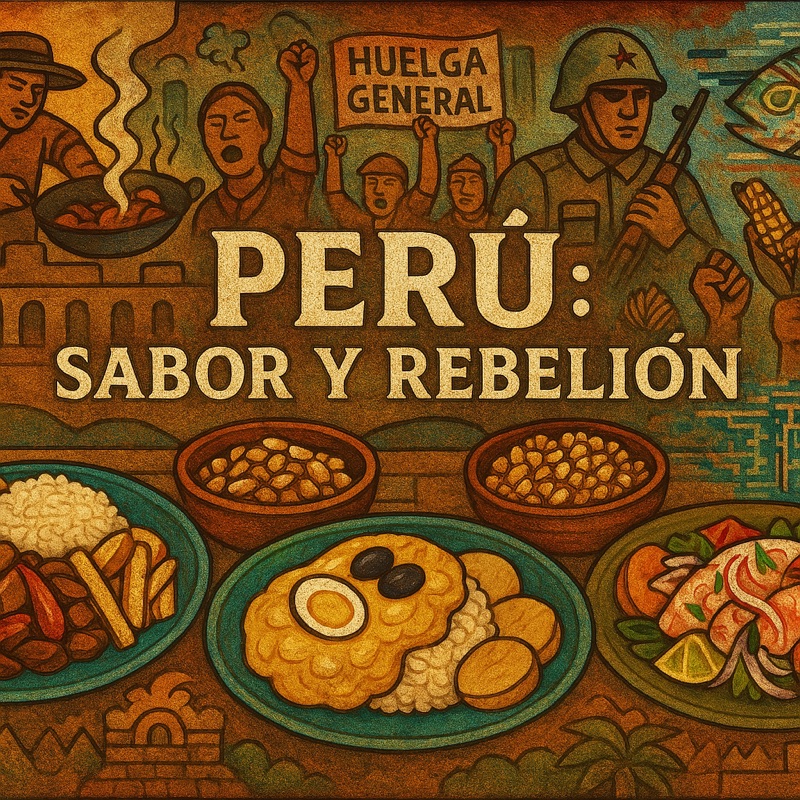

Peru: Sabor y Rebelión

Peru: Sabor y Rebelión

Nestled on the west coast of South America, among the Andes Mountains, on the edge of the Amazon Rainforest, is the ecologically superdiverse nation of Peru. This country was once home to one of the most advanced empires on Earth, that of the Incas. The suppression of this past and the taking of indigenous land by the Spanish led to an attempt to re-establish the grandeur of the Incan Empire by Túpac Amaru II. This failed, but the scars of this rebellion remain in the country to this day. In 1821, the independent nation of Peru was established. Thanks to a robust sector of natural resources, the importation of indentured servants, and strict adherence to a caste system, Peru started off as a much more stable country than many of the other colonies that became independent from Spain.

Yet, this fragile equilibrium would soon be disrupted. Throughout the 20th century, military juntas, relentless hyperinflation, and the unresolved wounds of colonial exploitation repeatedly upended the nation’s hopes for lasting peace. Peru’s cuisine reflects these struggles.

In Peru, the flavors of Spanish colonists, traditional indigenous foods, the survival foods of the enslaved, and the quick bites those in indentured servitude could steal combine to make a truly unique culinary mural. Today, we dive into the revolutionary narrative simmering in every Peruvian dish. We begin with the story of indentured Chinese laborers who, facing exploitation, ingeniously fused traditional stir-fry techniques with local ingredients—a culinary defiance that sparked its own rebellions. Then, we explore the velvety depths of Aji de Gallina—a creamy Creole stew whose makers took to the streets in 1919, demanding justice and change. Next, we savor the rich, garlicky aroma of Peruvian rice, whose unpretentious simplicity once sat at the very heart of 1948 riots against fascist austerity. We also recall how, in 1968, Indigenous laborers with toasted cancha corn in hand boldly re-occupied the lands that were once theirs. Finally, we examine the provocative role of Ceviche—the national dish turned propaganda tool in the early ‘90s, wielded against fishermen grappling with cholera outbreaks and the harsh boot of neoliberal austerity.

In Peru, every bite is a story, and every story, a fight.

Lomo Saltado: Stirring It Up

Lomo Saltado is perhaps the most iconic expression of Chifa cuisine—a uniquely Peruvian fusion of Chinese cooking techniques and Latin American ingredients. A sizzling stir-fry of onions, potatoes (in the form of French fries), hot peppers like ají amarillo, soy sauce, and thin strips of steak, it combines sizzling wok intensity with the local flavors of South America. The result is a dish that’s as vibrant as Peru itself. But behind its popularity lies a darker history—a scar carved by exploitation, survival, and resistance.

In 1854, Peru officially abolished slavery—nearly a decade before the Emancipation Proclamation in the United States. This milestone had been a long time coming, as the institution had been gradually dismantled since the 1820s. But even as slavery waned, Peru’s demand for cheap labor surged. The country’s booming guano industry—fueled by vast deposits of bat dung (yes, bat dung) essential to agriculture—required an enormous workforce. With enslaved labor no longer an option, Peruvian capitalists looked abroad.

In 1849, they found their answer in southern China. Over the following decades, roughly 100,000 men from Guangdong province were contracted as indentured laborers under what became known as the coolie trade. Though these contracts were technically voluntary, the reality was grim. Many workers were deceived, coerced, or kidnapped. Once in Peru, they faced brutal conditions in guano mines, on sugarcane plantations, and along the country’s nascent railroads—conditions hauntingly reminiscent of slavery. There were very few things that coolie laborers were able to bring from home, but one such thing was the Chinese cooking device known as the wok. The coolie laborers weren’t making the culinary fusion we now know as Lomo Saltado, but they started to flash-fry local ingredients (onions, peppers, beef) in the manner they were most used to, in order to survive these grueling conditions.

Of course, coolies did not take these abuses lying down. A series of coolie rebellions cut to the heart of the coolie trade. On Peru’s Chincha Islands, dubbed the “Islands of Hell,” in the 1850s, the indignities were particularly abhorrent. Over two-thirds of coolie laborers working these guano extraction sites died before their contract was up due to poor working conditions, malnutrition, and abuse by the overseers. In 1852, the coolies here had enough, began making makeshift weapons to attack their overseers, seized boats, and escaped the islands. This wouldn’t be the last time that coolies would fight back. In 1861, on Palpa Plantation in Ica, coolies began attacking guards and burning sugarcane fields, with some saying they took out their woks and began frying their dinners over the open flames. In the late 1860s, coolies began mass walk-offs from railroad sites. By the time the 1870s rolled around, the frequent rebellions not only began to make coolie labor economically untenable, they began to draw international attention to the practice. The Western world was “civilized” now, and slavery was a thing of the past. Peru’s major trading partners began to demand that something change.

In 1874, Peru enacted a treaty with China, effectively ending the coolie trade. Of course, the Chinese laborers now found themselves in Peru as a free people. They began experimenting with more extravagant flavors, and by the 1880s, Lomo Saltado became a staple of Peruvian cuisine. Much like modern Peru was built on the backs of indentured labor, Peruvian cuisine would celebrate the fusion of Asian and Latin American influences that were a reflection of a tumultuous past. For my own part, Lomo Saltado quickly became a new favorite, and it is not incredibly difficult to make.

Lomo Saltado (Beef Stir-Fry)

A Peruvian-Chinese fusion dish with stir-fried beef, vegetables, and fries, served with rice.

Ingredients (Serves 4):

• 1 lb beef sirloin or tenderloin, sliced into thin strips

• 2 tbsp soy sauce

• 2 tbsp red wine vinegar

• 1 tsp ground cumin

• 1 red onion, sliced into wedges

• 1 red bell pepper, sliced

• 2 tomatoes, sliced into wedges

• 1 ají amarillo pepper, sliced (or jalapeño)

• 2 garlic cloves, minced

• 2 tbsp vegetable oil

• ¼ cup chopped cilantro

• Salt and pepper to taste

• 2 cups French fries, freshly cooked

Instructions:

1. Marinate beef strips in soy sauce, vinegar, cumin, salt, and pepper for 10 minutes.

2. Heat 1 tbsp oil in a large skillet or wok over high heat. Stir-fry beef for 2–3 minutes until browned. Remove and set aside.

3. Add remaining oil to the skillet. Sauté garlic, onion, bell pepper, and ají amarillo for 2 minutes. Add tomatoes and cook for 1 minute.

4. Return beef to the skillet, toss with vegetables, and mix in fries and cilantro. Adjust seasoning.

5. Serve immediately with rice.

Tips: Cook fries fresh for best texture. Keep the stir-fry quick to retain vegetable crunch.

Aji de Gallina: Stewing in Rage

Aji de Gallina is a rich chicken stew flavored with walnuts, cheese, ají amarillo peppers, and made with a base of bread soaked in milk. While it is unknown precisely who started making it, whether it was Creole chefs in bondage adapting recipes to local ingredients or French chefs fleeing the revolution, this savory stew became a staple of Peru’s Creole cuisine. It was, of course, this Creole base that powered the urban workforce in the early 1900s, the same workforce that found themselves aflame in 1919.

Peru was not a major player in the First World War, but the economic effects were palpable. The cost of living for Lima’s working poor doubled. This meant a working-class staple like Aji de Gallina became impossible to afford. When a law passed restricting women and children from working beyond 8-hour workdays, rather than making things better for workers, the men were merely made to pick up the slack and work long hours in dangerous conditions. At the time, Peru was known throughout the world as the “Aristocratic Republic,” as it found much more stability than its neighbors, but at the cost of a regimented social structure. The climate was ripe for revolutionary protest.

In December of 1918, textile workers began walking out, demanding a 50% wage increase and an 8-hour workday for all. By the beginning of 1919, this expanded to a full general strike, with all of Lima paralyzed for several days. Aji de Gallina became both a communal staple of the strikers, with people bringing what bread they could for the stew’s base, and massive pots cooking the stew to dole out to strikers.

President José Pardo y Barreda initially met the strike with heavy-handed tactics, arresting strike leaders and sending in riot police, but the economic paralysis proved too much. The Aji de Gallina pots just kept going, and strikers kept striking. The government eventually relented and enacted an eight-hour workday, leading to the end of the strikes.

Politically, this event destabilized the government, with the oligarchy divided and weak, and the working class newly awakened. The government was overthrown in a coup by former President Augusto B. Leguía, officially ending the “Aristocratic Republic.” He initially presented himself as a champion of the working class but quickly pivoted to a personality-based nationalist regime known as the “Oncenio” for its 11-year period. He would be overthrown by the military, and coups would become the norm in Peru for a very long time. The working class would become involved in organized politics for the first time and begin such political parties as the Communist Party of Peru and, most notably, the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (or APRA), which would stand as a radical workers’ anti-imperialist party before becoming a major part of Peru’s political system for years to come. Through it all, Aji de Gallina continued to provide sustenance to the workers of Peru, its creamy, simple ingredients becoming a warm comfort through tough times.

Aji de Gallina was one of the most unique dishes I’ve ever had the pleasure of making. The way it comes together and thickens is so interesting, and the taste, the taste is beyond rewarding.

Aji de Gallina (Creamy Chicken Stew)

A creamy, spicy chicken dish with a nutty sauce, served with rice and boiled potatoes.

Ingredients (Serves 4):

• 2 chicken breasts (about 1 lb), cooked and shredded

• 2 cups chicken broth

• 2 slices white bread, crusts removed, soaked in ½ cup milk

• 2 ají amarillo peppers, seeded and blended (or 2 tbsp ají amarillo paste)

• 1 onion, finely chopped

• 2 garlic cloves, minced

• ¼ cup ground walnuts or pecans

• ¼ cup grated Parmesan cheese

• 2 tbsp vegetable oil

• Salt and pepper to taste

• 2 boiled potatoes, sliced

• 2 hard-boiled eggs, sliced

• Black olives for garnish

Instructions:

1. Heat oil in a large pan over medium heat. Sauté onion and garlic until soft, about 5 minutes.

2. Add ají amarillo paste and cook for 2 minutes. Blend soaked bread with milk until smooth, then add to the pan.

3. Stir in chicken broth, shredded chicken, ground nuts, and Parmesan. Simmer for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally, until thickened. Season with salt and pepper.

4. Serve over rice with boiled potato slices, garnished with egg slices and olives.

Tips: If ají amarillo is unavailable, substitute with a mix of yellow bell pepper and a pinch of chili powder.

Arroz al Ajo: The Grains of Wrath

It goes without saying that rice is a staple in Peru. It wasn’t native to the area, but once introduced by the Spanish in the 1600s, rice never left the side of Peru’s food. Peruvian rice is also almost always cooked with garlic. The simple yet flavorful combination of white rice and garlic makes Peruvian rice in particular a great pairing with any number of dishes. Of course, when something that essential becomes scarce, people don’t just grumble—they riot.

By the end of the 1940s, Peru was in upheaval. President José Luis Bustamante y Rivero was in constant contention with the working class of Peru, represented by the APRA Party. While Peru’s government attempted to enact price controls on things such as rice, inflation continued to creep up. Daily demonstrations over the cost of staples such as rice rocked all sectors of Peru. People began to look for anything to bring stability to the country.

The Minister of Government and Police was a war hero named Manuel A. Odría. He was extremely right-wing and began to seethe at Bustamante’s back-and-forth with the APRA Party. In 1948, he led a military coup, pledging to “end the misery.” His first act was to outlaw the APRA Party and drastically cut government spending, enacting crippling austerity measures and oppressive political measures. Ruling as a fascist dictator, people began to be able to afford staples, but only the most bare-bones essentials: garlic, oil, and rice. It worked for a time, ringing in the “Ochenio” period of Peruvian politics.

Odría’s government initially was able to ride the wave of an increase in foreign business. The Korean War led to a spike in activity in Peru’s commodities market. But by the middle of the 1950s, this spike began to slow, and prices began to rise again. People also began to tire of political repression, as well as “rice austerity.”

By the middle of the 1950s, demonstrations and strikes became nearly constant. All the repression in the world could not disguise people’s disgust with the regime. The straw that broke the camel’s back was in Peru’s second-largest city, the southern city of Arequipa.

Arequipa is notable as the site that started the 1948 coup. In 1956, Arequipa’s students started staging public protests against the regime’s political repression. Ordinary citizens began joining in, once again protesting the price of rice. The government’s response was to send troops to suppress these demonstrations and brutalize protesters. But something strange happened.

Rather than join in, the troops began to join the protests. One general, General Marcial Merino Pereira, began to give speeches calling for the return of democracy. With this event highlighting the fragility of his regime, Odría called elections for the end of that year, elections that he lost. Peru would see a number of years of democracy in the years after, but the tricky working-class issues would persist. Garlicky rice, of course, would remain a staple.

There is something artistic about the simplicity of garlic rice that cannot be beat. I find it goes well with everything.

Peruvian Garlic Rice (Arroz al Ajo)

A simple yet flavorful rice dish, perfect as a side for many Peruvian meals.

Ingredients (Serves 4):

• 2 cups long-grain white rice (Jasmine rice is a good choice for its aroma and texture)

• 3 cups water (or chicken broth for richer flavor)

• 3–4 cloves garlic, minced

• 2 tbsp vegetable oil (or a mix of vegetable oil and butter for added richness)

• 1 tsp salt (or to taste)

Instructions:

1. Sauté the Garlic: In a medium-sized pot with a tight-fitting lid, heat the oil over medium heat. Add the minced garlic and sauté for about 30 seconds to 1 minute, until fragrant, but do not let it brown or burn, as this can make it bitter.

2. Toast the Rice: Add the rinsed and drained rice to the pot with the garlic and oil. Stir well to coat each grain of rice. Cook for 1–2 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the rice appears slightly translucent around the edges.

3. Add Liquid and Seasoning: Pour in the water (or broth) and add the salt. Stir once to combine everything.

4. Boil and Simmer: Bring the mixture to a rolling boil over high heat. Once boiling, reduce the heat to the lowest setting and cover the pot tightly with the lid.

5. Cook the Rice: Let the rice simmer undisturbed for 15–18 minutes, or until all the liquid has been absorbed and small “craters” appear on the surface of the rice. Do not lift the lid during this time.

6. Rest and Fluff: Once cooked, remove the pot from the heat and let it rest, still covered, for 5–10 minutes. This allows the steam to redistribute and makes the rice even fluffier.

7. Serve: Fluff the rice gently with a fork before serving.

Cancha: Corned Beef

Cancha, or toasted corn, has been enjoyed by the people of the Andes for millennia. These large kernels don’t quite pop; they just expand in size and make a nice, crunchy snack. Toasted on pans near open fires, the Indigenous people of the Andes often carried these around as a staple with cheese, a snack dating back to Incan times. They can be found as an appetizer at Peruvian restaurants, a side for such dishes as ceviche, and enjoyed, as mentioned before, on their own. But, perhaps most importantly, they are a symbol of Peru’s Indigenous culture. This culture, and its survival, exploded into prominence in 1968. Just as cancha endured through centuries of upheaval, Peru’s Indigenous communities found themselves fighting once again—this time, for the land that had been stolen from them.

In 1968, Peru’s mountain landscape, which had once been the home base of the Incan Empire, was divided into vast haciendas, plantations that employed the people who had once lived there to work in back-breaking labor in order to live on their own ancestral lands. Reform of this system had doomed several Peruvian presidencies, and patience among Peru’s Indigenous population was wearing thin. A military coup by a leftist military officer named Juan Velasco Alvarado proved their opportunity.

Juan Velasco Alvarado led a coup in 1968 that overthrew the civilian government. But, unlike previous coups, which were instigated by the right, this one had been primarily driven by concerns important to Peru’s political left. First and foremost of these was the nationalization of key industries that had been owned by foreign corporations. One sign of promise for the Andean population was that, unlike past military rulers, Velasco saw Peru’s land inequality as a structural injustice that had to be undone at its roots and promised change.

The Indigenous workers weren’t waiting around for promises. They started occupying haciendas, kicking out the feudal overlords and claiming what was theirs. Picture this: families roasting cancha over makeshift fires, the smoky scent mixing with the crackle of defiance as they turned their ancestral snack into a victory feast. It was a message to Velasco—follow through, or we’ll keep pushing. The occupations weren’t a picnic, though. The landowning elite fought back hard, hiring private militias to scare off occupiers, even torching crops to leave nothing behind. They screamed at Velasco to shut it down, but the general wasn’t backing off. In 1969, he dropped the Agrarian Reform Law, handing millions of acres to Indigenous and peasant cooperatives. The hacendados got agrarian bonds as “compensation,” but most spat on them, saying they were worth less than dirt.

During those tense occupations, cancha was a lifeline. It was easy to carry, quick to roast, and gave you the energy to hold your ground. Indigenous workers munched on it with cheese and dried meats, keeping watch over their reclaimed fields. It wasn’t just food—it was a middle finger to the idea that they could be starved into giving up. But the wins didn’t last. With burned infrastructure and landowners digging in their heels, the reforms started to crumble. In 1975, a right-wing military coup ousted Velasco, kicking off a backslide that undid much of his work. Maoist guerrillas like the Shining Path tried to push further, but their violence scared folks into backing increasingly hardline governments. By the ‘80s, hyperinflation hit, and a Japanese-Peruvian economist named Alberto Fujimori took the reins, setting the stage to re-privatize those hard-won lands. Through it all—coups, reforms, guerrillas, privatization—cancha stayed a constant, a crunchy reminder of what endures.

I don’t have many notes other than cancha is a delightful, crunchy snack that popcorn lovers will find great!

Cancha (Toasted Corn Kernels)

A crunchy snack made from dried corn, often served as a side or appetizer.

Ingredients (Serves 4):

• 2 cups dried Peruvian corn (maíz chulpe or cancha corn)

• 2 tbsp vegetable oil

• Salt to taste

Instructions:

1. Heat oil in a large skillet over medium heat.

2. Add dried corn kernels and stir constantly to prevent burning. Cook for 10–15 minutes until kernels are golden and puffed.

3. Remove from heat, drain on paper towels, and sprinkle with salt.

4. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Ceviche: Fujimori’s Fishy Fujishock

Ceviche is the most interesting of dishes. Doused in lime juice, fish reacts in a way that gives it the texture and properties of being cooked. This has been done among Peruvian coast-dwellers for centuries, and ceviche itself, the fish combined with various types of garnish and peppers, has evolved to become Peru’s national dish. The fishermen and dock workers who form Peru’s coastal working class live off of ceviche, and it is strongly linked to their livelihoods. Of course, when neoliberalism hit in the 1990s, with the associated downsides, it became subverted as propaganda.

Much like Javier Milei has in Argentina, Alberto Fujimori’s victory in the 1990s elections caught many by surprise. A right-wing gadfly college professor with a television program, Fujimori ascended to the presidency with the goal of slashing a century’s worth of government programs. His campaign spoke to a population sick of Shining Path guerrillas and hyperinflation with an outsider image, but there is much evidence that he had prior knowledge and collaboration with the military on Plan Verde. This was a plan concocted by members of the military to exterminate much of the Indigenous population and institute an authoritarian regime.

Regardless of his connection, Fujimori, like Pinochet in Chile, enacted a strict program of cuts to social spending known as Fujishock. His administration slashed social spending, gutted subsidies, froze wages, and unleashed a wave of privatizations. Coastal workers were left gasping for air. Fishermen saw fuel prices spike, food prices climb, and markets destabilize. Entire communities that had lived off the sea were now drowning in austerity.

Then came the cholera.

In 1991, Peru was hit by its first cholera outbreak in over a century. It spread rapidly through poor, under-resourced coastal regions—exposing the catastrophic failures of Peru’s hollowed-out public health system. Rather than invest in sanitation and clean water infrastructure, the government did what any image-obsessed regime might do: it blamed the victims. Fishermen were scapegoated. Ceviche—once a national treasure—was suddenly framed as a health hazard. Sales plummeted. Street vendors were ruined. Families that relied on ceviche for income were devastated overnight.

In order to calm the public, get control of the issue, and boost the struggling fishing industry, Fujimori hatched a plan to prove everything was okay. On live TV, Fujimori ate a plate of ceviche. Of course, this ran directly contrary to the government’s warnings about eating raw fish. People took the message to heart and started ignoring government health warnings. As a result, the crisis deepened, and more people died. Within days of the stunt, even Fujimori’s own health minister contracted cholera.

Of course, Fujimori was fine using his own government as scapegoats. Citing bureaucratic hurdles, he staged a “self-coup” in 1992 with the military, dissolved the legislature, and dismissed many of his own civilian ministers. Much like his televised ceviche stunt, Fujimori’s self-coup was a performance—one designed to frame himself as Peru’s sole problem-solver while scapegoating his own government. But just as eating raw fish couldn’t undo a cholera outbreak, dissolving Congress couldn’t mask the growing cracks in his rule, which compounded over time. In 2000, external pressure became too much, and Fujimori fled to Japan, a country that would shield him from extradition, faxing his resignation from abroad.

Ceviche itself would recover and remains internationally recognized as Peru’s national dish. Making it is incredible if you’ve never done so before. You really don’t understand how magical it is to watch the lime juice transform the fish. Just make sure you buy enough limes.

Ceviche (Peruvian Fish Ceviche)

A refreshing dish of raw fish marinated in lime juice, served with onions, cilantro, and chili.

Ingredients (Serves 4):

• 1 lb fresh white fish (tilapia, sea bass, or cod), cut into ½-inch cubes

• 1 cup fresh lime juice (about 8–10 limes)

• 1 red onion, thinly sliced

• 1–2 ají amarillo peppers (or habanero), seeded and finely chopped

• 1 tbsp chopped cilantro

• 1 garlic clove, minced

• Salt and pepper to taste

• 1 boiled sweet potato, sliced

• 1 cup boiled corn kernels (or choclo)

• Lettuce leaves for serving

Instructions:

1. Place fish cubes in a glass bowl. Sprinkle with salt and cover with lime juice. Stir gently and let marinate in the fridge for 10–15 minutes until fish turns opaque.

2. Add red onion, ají amarillo, garlic, and cilantro to the bowl. Mix gently and season with salt and pepper.

3. Serve immediately on a bed of lettuce, garnished with sweet potato slices and corn kernels.

Comments

Post a Comment