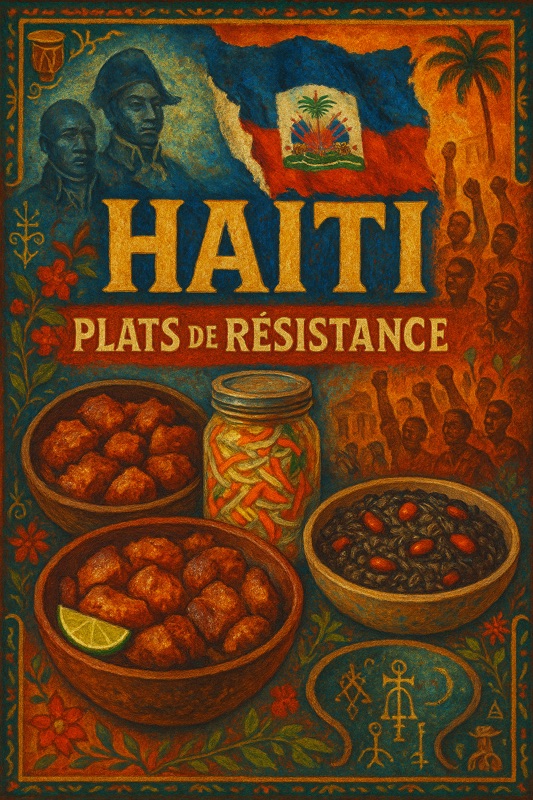

Haiti: Plats de Résistance

Haiti: Plats de Résistance

Yesterday, May 18, was Haitian Flag Day. It marks the moment in 1803 when revolutionary leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines tore the white from the French tricolor, declaring that Haiti’s banner would be one of liberty or death. It wasn’t just the birth of a flag. It was the birth of a nation forged in fire. In 1804, Haiti became the second independent country in the Western Hemisphere and the first to rise from the ashes of slavery, built by the only successful slave revolt in modern history.

Today, Haiti is often labeled the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere. Some blame political instability or recent crises like the 2021 assassination. Others—like Pat Robertson—infamously claimed Haiti’s woes stem from “deals with the devil” during its revolution. But the truth lies elsewhere: in debt imposed by Western powers, foreign occupations, U.S.-backed coups, and homegrown tyrants. The Haitian people have never been handed freedom—they’ve had to fight for it, over and over again.

And they have. From the sugarcane fields to the garment factories, Haiti resists. It resists in the streets, in the markets, in the kitchens. Haitian cuisine is built from this resistance. Its flavors are not just delicious; they are the spice of the rebellion. Today we will talk about just how they have flavored Haiti’s history of revolution.

We will talk about the Haitian Revolution, and how a dish of marinated and fried pork connected a new nation with its people’s African roots. We will discuss how the West forced Haiti to exorbitant debts for lost slaves, how the US occupied the nation to ensure those debts were paid, and the spaghetti dish that came from the US but was remade into a Haitian icon. We discuss the homegrown dictators of the Duvalier family, and the northern mushroom dish that sparked a rebellion against him. We discuss the hope of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, his commitment to the working class and how that cost him, and the resilience of a slaw dish in the face of austerity imposed by Aristide’s predecessors. Finally, we will discuss how Aristide’s second removal sparked protests on Flag Day 2004, and how a popular Flag Day potato dish was subverted as a symbol of resilience.

Get your epis and sauce ti-malice ready as we dig in.

Griot: Marinated Resistance

In West African culture, Griots are historians and storytellers who hold a special significance in the community. They are used almost as a living history book, imbued with rich stories of a people’s past, passing this rich oral tradition from generation to generation.

However, in Haiti this name has a different connotation. It refers to a dish of marinated, braised, and fried pork, soaking in the flavors of citrus and epis, a Haitian cooking base, that has become Haiti’s national dish. Like the storytellers of West Africa, the Haitian dish of griot is steeped in legacy and tradition, its roots tracing back to marinated meats brought to the French colony of Saint-Domingue by enslaved Africans.

Pork was originally a luxury reserved for the colonial elite. But like all things, the Revolution upended the order—what was once a dish of the privileged became a meal of the liberated. It was this role reversal and reclamation that gave it the name griot, becoming a meal intricately associated with the establishment of Haiti itself.

Before Haiti became Haiti, it was Saint-Domingue, a French colony and the crown jewel of France’s empire, built on the backs of enslaved Africans working vast sugar plantations. A rigid racial hierarchy defined life there: the enslaved at the bottom, free people of color (often mixed-race) facing severe discrimination, and the white colonial elite at the top, enjoying luxuries like pork while slaves labored relentlessly. The cooking techniques for griot, brought from Africa, were adapted in this harsh environment, with enslaved workers raising pigs in secret to reclaim a taste of freedom.

In the 1780s, the ideals of the French Revolution—liberty, equality, fraternity—reached Saint-Domingue, igniting unrest. Free people of color and Creole merchants petitioned France’s National Assembly for equal rights and the abolition of slavery, but their demands were met with brutal rejection, including public torture as “counter-revolutionaries.” As France’s revolutionary government neglected its colonies, the Code Noir—a set of laws offering minimal protections to slaves and free people of color—was ignored, stirring racial animosities.

In 1791, a number of free people of color and slave foremen met in secret at a plantation in the North and planned a revolt. For their leader, they picked a freed former slave named Toussaint L'Ouverture, who was a skilled orator and self-educated writer. The Rebellion was started with a massive public voodoo ceremony in the north of the colony, amongst the largest plantations and most escaped slaves. Voodoo was, of course, a uniquely Haitian religion, a synthesis of Christianity, West African religious traditions, and indigenous ceremonies, much like the cuisine of the island colony. Voodoo was not just faith; it was a rallying cry for a unique people, searching for the strength deep inside to rise up against their oppressors despite the long odds of it succeeding.

L'Ouverture would prove to be a fearless general and political leader, training his troops in the arts of European combat and guerilla warfare, and making treaties with the Spanish and English as he saw fit. As France was embroiled in its own revolutionary struggles, the army of freed slaves made great progress liberating the plantations and fighting off the military forces on the island. As they liberated slaves, they also liberated stores of food, including pork. Former slaves not only seized freedom, but seized their own tables, being able to taste the marinated brilliance of griot as free people for the first time.

In order to maintain control of their colony, and not let it fall to the Spanish or the British, the French abolished slavery in all of its colonies in 1794. This served multiple purposes. For the French people, struggling with the chaos of a revolution, it showed a moral victory over the royalist powers. It also took the air out of the rebellion in Haiti, and Toussaint L'Ouverture turned legal control of the colony back to France, while still operating as a de facto independent entity. This worked, for a time. Griot scented the air of Saint-Domingue as a free people fried it in celebration.

Toussaint did not rest on his laurels. He would take his army and seek to free slaves in both Jamaica and Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), and would need to fight local rivals in the South and North, who were intent on keeping Haiti a slave republic. After uniting the colony, Toussaint would start to write declarations stating that Haiti should be a republic for people of color and by people of color. This would get the attention of Napoleon Bonaparte, who in 1801 would send an expeditionary force to Saint-Domingue to re-establish direct French control, and attempt to re-impose slavery, and the profits it produced, to fund his wartime efforts in Europe. In 1802, Toussaint L'Ouverture would be captured and deported to Europe to face his death.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Toussaint L'Ouverture’s closest advisor and friend, would take on the torch of revolution. He would declare the nation of Haiti independent in 1804 after several decisive victories against the French, and would declare himself emperor of a newly independent Haiti. With the fear of the return of the French and slavery, Dessalines would order the execution of the French remaining in the colony, exempting German traders who did not take part in the slave trade, and Polish mercenaries who defected from the French army. He would classify this newly exempted class as people of color within Haiti’s new legal code, establishing a new hierarchy that turned the old one on its head. Those early years are still controversial, with many citing Jacques I (his chosen name of royalty) as a brutal genocidal dictator. For the newly free Haitians, eating griot as free people, the question was not just philosophical—it was survival. Much in the realm of what John Milton once asked, if France had made Haiti hell, was it better to reign in it, or serve under its chains?

There were several times while I was making griot where I questioned whether I was making it right. Was there enough marinade? Was I braising it too much? Would frying ruin the taste? However, it came out tasty, and it will definitely be a favorite of mine going forward.

- Griot with Sauce Ti-Malice Recipe

- Serves: 4–6

- Prep Time: 15 minutes

- Cook Time: 1 hour

- Marinating Time: 4 hours (or overnight)

Total Time: 5 hours 15 minutes (or overnight)

- Ingredients:

Griot:

- 2 lbs pork shoulder, cut into 1-inch cubes

- 1/2 cup sour orange juice (or 1/4 cup lime juice + 1/4 cup orange juice)

- 2 tbsp Revolution Epis (see below)

- 1/4 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- 2 tsp fresh thyme leaves (or 1 tsp dried thyme)

- 1 tsp salt

- 1/2 tsp black pepper

- Vegetable oil, for frying (about 2 cups)

- 1/4 cup fresh parsley, chopped (for garnish)

Sauce Ti-Malice:

- 1 medium onion, thinly sliced

- 1/4 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 2 garlic cloves, minced

- 1/4 cup lime juice

- 1/4 cup white vinegar

- 1/2 cup water

- 1 tbsp olive oil

- 1 tsp salt

- 1/2 tsp black pepper

- 1 tsp fresh thyme leaves (optional)

- Instructions:

Griot:

- In a large bowl, combine pork, sour orange juice, Revolution Epis, Scotch bonnet powder, onion, thyme, salt, and pepper. Mix well to coat. Cover and marinate in the refrigerator for at least 4 hours, preferably overnight.

- Transfer pork and marinade to a large pot. Add 1 cup water, bring to a simmer over medium heat, and cook until pork is tender, about 45–50 minutes, stirring occasionally. Reserve 1/4 cup cooking liquid.

- In a deep skillet or Dutch oven, heat 2 inches of vegetable oil to 350°F (175°C) over medium-high heat. Remove pork from pot, draining excess liquid, and fry in batches until golden and crispy, about 5–7 minutes per batch, turning occasionally.

- Drain on paper towels. Keep warm in a low oven (200°F) while frying remaining batches.

- Garnish with parsley and serve hot with Sauce Ti-Malice and Pikliz.

Sauce Ti-Malice:

- In a small saucepan, heat olive oil over medium heat. Add onion and garlic; sauté until soft, about 3–4 minutes.

- Add Scotch bonnet powder, lime juice, vinegar, water, salt, pepper, and thyme (if using). Bring to a simmer and cook for 5 minutes, stirring occasionally, until slightly thickened.

- Remove from heat and let cool slightly. Serve warm or at room temperature alongside Griot, or store in a jar in the refrigerator for up to 1 week.

- Revolution Epis Recipe

- Description: A foundational Haitian seasoning for Griot.

Makes: About 1 cup

Ingredients:

- 1 red bell pepper, roughly chopped

- 1/2 onion, roughly chopped

- 3 garlic cloves, peeled

- 1/2 cup fresh parsley, chopped

- 2 scallions, chopped

- 1/4 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 2 sprigs fresh thyme, leaves only

- 1/3 cup sour orange juice (or 2 tbsp lime juice + 2 tbsp orange juice)

- 1/4 cup olive oil

- 1 tbsp white vinegar

- 1 tsp salt

Instructions:

- In a blender, combine bell pepper, onion, garlic, parsley, scallions, Scotch bonnet powder, thyme, and salt. Pulse until finely chopped, about 20 seconds.

- Add sour orange juice, olive oil, and vinegar. Blend into a coarse paste, about 10 seconds.

- Store in a sealed jar in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks. Use 2 tbsp for Griot.

Espageti: Spaghetti Remix ft. USA

In the early 1900s, the USA graciously “exported freedom” to Haiti, much as it had done in Puerto Rico and the Philippines a mere two decades prior. Of course, American freedom has a peculiar shape: it often looks a lot like occupation, and the US occupied Haiti from 1915–1934, before deciding Haiti had been sufficiently ‘liberated’ and withdrawing. One thing the Americans did bring during the occupation was food. Spaghetti, hot dogs, and ketchup were standard issue fare by the US military. However, the Haitians, being a people who excel at adaptation, took these foods and made a uniquely Haitian breakfast dish. By the time the US left, Espageti was a popular street food for the working class of Haiti. Of course, the story of why the US was there, and how the food was adapted, deserves to be told.

Haiti is a nation that has been looked upon with scorn by the Western powers since the very start. From the moment Haiti claimed independence, the West made sure it remained shackled, not in chains, but in debt. In order to normalize relations with the powers of Europe, Haiti was made to take on a substantial debt to repay France for its lost slaves. This debt of 150 million francs would take from 1825–1947 to repay, and cripple the young nation as other neighboring nations, like the US, were able to stand on their own two feet.

Of course, burdened by such immense debt, Haiti turned to selling its natural resources to stay afloat. Its political situation was fraught with instability, with presidents chosen by a fractious senate, and a series of “Empires,” “Kingdoms,” and “Republics” established throughout the 1800s. Meanwhile, the neighboring colony of Santo Domingo—later the independent Dominican Republic—remained constantly at odds with Haiti.

Although its sugar plantations were no longer owned by French slaveholders, foreign investments, particularly from German and American capital, began exerting significant influence. German landowners, descended from those originally exempted from Haiti’s early ban on foreign white landowners during the revolution, maintained a stranglehold on the country’s economy. By the late 1800s, Haiti was heavily in debt—owing its freedom to France, its infrastructure to Germany, and its business operations to the U.S.—trapped by foreign hands tightening their grip.

As the political instability continued, and the influence of German investment grew, US business interests grew increasingly worried. World War I was on the verge of breaking out in Europe, and the US was concerned about a German outpost on its front yard. In addition, it grew concerned about the money it was owed. The outbreak of the war in Europe would provide a window of opportunity.

In 1914, US president Woodrow Wilson would order US Marines to storm Haiti and take $500,000 in gold from the Haitian National Bank and bring it to New York City for safekeeping, giving the US control of Haiti’s finances. This was not the end, however. As in 1915, Haiti’s pro-American president Vilbrun Guillaume Sam was assassinated by rebels led by the anti-American leader Dr. Rosalvo Bobo, prompting the US to invade.

The US set to work immediately, installing a new president, Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave, a member of the mulatto elite and senate president. It then took over Haiti’s customs houses and all its administrative institutions, redirecting 40% of Haiti’s income to pay down debt to the US and France. By the end of 1915, Haiti’s legislature granted the US economic and security oversight for a 10-year period, under threat of aid payments being suspended if they didn’t sign it. US rule would establish a corvée system, a form of state-imposed unpaid labor or slavery, in order to rapidly finish building out Haiti’s infrastructure. The US military would be the ultimate authority during this time, and would establish a permanent presence in Haiti. They brought with them spaghetti, hot dogs, and ketchup, which became a cheap food for the working-class population after dealing with crippling austerity and legalized slavery imposed by the US.

It wouldn’t be long before the Haitians, whose national identity is tied to resistance to slavery, began to see the US as establishing a new form of slavery. Groups of rebels, called Cacos, would begin a guerilla war against the US, often supported by the German government. Cacos are birds native to Haiti, known for ambushing their prey. Like their namesake, the Cacos struck fast, hit hard, and vanished into the mountains—a rebellion built on ambush and defiance. The US crushed the first Cacos rebellion shortly after it started, and would further entrench themselves in the country’s affairs by forcing an amendment to the Constitution that would overturn the ban on foreigners owning land that had been in existence since the Revolution in 1804. The legislature would not support amending the Constitution, so the US would dissolve Haiti’s legislature for 10 years.

The end of World War I in 1918 would mean that German influence in the Caribbean ended. But this did not dissuade the rebels, with a new Cacos Rebellion rising, one that involved at least 20% of Haiti’s population. As Woodrow Wilson proudly claimed that he supported making a world safe for democracy at the end of World War I, US troops would brutally put down Haitians fighting for their independence and control of their destinies. It was around this time that espageti became a staple of the Cacos diet. Easy to prepare and cook, it proved to be revolutionary fuel.

Throughout the 20s, the US would begin to get frustrated with rebellion, as its puppet governments would expand the forced unpaid labor practices, and the US would divert even more money to repay American investors, taking complete control of the Bank of Haiti. In 1929, Haitians would take to the streets, demanding direct elections and an end to occupations, with US marines firing on and killing several Haitians in the Les Cayes massacre. The streets were left empty, with spaghetti stalls on the streets serving as a reminder of the deep scar the American occupation had left on the country.

This would prompt President Herbert Hoover to order an investigation, and then finally in 1933 under FDR’s good neighbor policy, the US and Haiti would agree to a US withdrawal, the US finally establishing freedom within its neighbor. Espageti remains a working-class staple to this very day.

Espageti, I found to be an odd sort of beautiful mix, a spicy take on spaghetti and meatballs. I have found epis to be a cooking base that I love, and will likely start incorporating into other things.

- Haitian Espageti Recipe

- Serves: 4

- Prep Time: 15 minutes

- Cook Time: 20 minutes

Total Time: 35 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1 lb spaghetti (or linguine/vermicelli)

- 12 oz hot dogs, sliced into 1/4-inch rounds (or 1/2 cup smoked herring, soaked and shredded)

- 1 medium onion, thinly sliced

- 1 green bell pepper, diced

- 3 garlic cloves, minced

- 1/4 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 9 tbsp tomato paste

- 2 cups reserved pasta water

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 2 tbsp Cacos Fire Epis (see below)

- 1/4 cup fresh parsley, chopped

- 3 sprigs fresh thyme, leaves only (or 1 tsp dried thyme)

- 1 tsp salt, or to taste

- 1/2 tsp black pepper, or to taste

Instructions:

- Cook spaghetti in a large pot of salted boiling water until al dente, about 8–10 minutes. Reserve 2 cups pasta water, then drain and set aside.

- In a large skillet, heat olive oil over medium heat. Add hot dogs (or herring); cook until browned, 5–7 minutes. Remove and set aside on a plate.

- In the same skillet, add bell pepper, half the onion, and garlic. Sauté until soft, 3–4 minutes, stirring constantly.

- Add tomato paste, Scotch bonnet powder, and Cacos Fire Epis; stir for 1 minute. Add 1/4 cup pasta water to loosen paste, mixing well. Return hot dogs (or herring) to skillet; stir to combine.

- Reduce heat to low. Add cooked spaghetti, salt, pepper, parsley, thyme, and remaining pasta water (as needed for moisture). Toss well to coat.

- Cover and cook 2 minutes to meld flavors. Serve hot, garnished with remaining onion slices.

Notes:

- Sourcing: Use spaghetti or linguine; avoid angel hair. Scotch bonnet powder in Epis and sauce adds bold heat.

- Storage: Refrigerate for up to 2 days; reheat with a splash of water.

- Cacos Fire Epis Recipe

- Description: A fiery seasoning for Espageti.

Makes: About 1 cup

Ingredients:

- 1 green bell pepper, roughly chopped

- 1/2 onion, roughly chopped

- 4 garlic cloves, peeled

- 1/4 cup fresh parsley, chopped

- 2 scallions, chopped

- 1/4 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 2 sprigs fresh thyme, leaves only

- 1/4 cup olive oil

- 1/4 cup white vinegar

- 1 tsp smoked paprika

- 1 tsp salt

- 1/2 tsp black pepper

Instructions:

- In a blender, combine bell pepper, onion, garlic, parsley, scallions, Scotch bonnet powder, thyme, smoked paprika, salt, and pepper. Pulse until finely chopped, about 20 seconds.

- Add olive oil and vinegar. Blend into a coarse paste, about 10 seconds.

- Store in a sealed jar in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks. Use 2 tbsp for Haitian Espageti.

- Substitute:

If unavailable, mix 1 tbsp minced garlic, 1 tsp hot sauce, 1 tsp dried thyme, 1 tsp smoked paprika, and 1 tbsp vinegar.

Diri Ak Djon Djon: Black Rice For Black Years

In the north of Haiti, a mushroom called the djon djon mushroom grows. For centuries, the people of the north have boiled the mushroom, removed it, and used the black broth to cook rice, infusing it with a natural, earthy flavor and a striking black hue. With its deep roots in the North and its status as a Haitian icon, it would become a crucial part of Haiti’s resistance in the years to come. A homegrown oppressor would rise in Haiti, feasting on its rotting corpse as the djon djon mushroom fed on decaying wood. The dark broth of Diri Ak Djon Djon would come to embody both the blackness of the years ahead and the struggle for survival that defined them.

In 1950, after years and years of instability, American occupation, and military juntas, direct democratic elections for president were held for the first time in the nation’s history in 1950. The person who won, Paul Magloire, was an elite Colonel in the military. After a devastating hurricane struck Haiti, President Magloire did not rebuild—he fled, taking relief money with him and leaving a shattered nation in his wake. In the ruins left behind, a quiet, calculating doctor named François Duvalier (known as “Papa Doc”) stepped forward, rallying rural Haitians with promises of justice—an end to corruption, an end to colonial and elite exploitation.

Duvalier’s Party, the National Unity Party, swept the legislature in the 1957 elections, and Duvalier himself became president with a substantial victory. At first, his reign seemed promising—his words carried hope for Haiti’s forgotten poor. But behind the speeches, shadows gathered. He began exiling the supporters of his political opponents, painting them as wealthy supporters of colonialism. After a failed 1958 coup, Duvalier’s paranoia hardened into strategy—he moved to dismantle Haiti’s military, replacing it with a force that owed loyalty only to him.

Duvalier began to incorporate voodoo mysticism into his rule, and the new rural police force he established, which became known as the Tonton Macoute after a boogeyman figure from Haitian voodoo, would help to silence dissent as a terrifying secret police force. He often took part in their tortures of his political opponents himself, watching with a ceremonial voodoo death mask. He started to expel all foreign-born bishops from Haiti, becoming excommunicated from the Catholic Church.

By 1963, he had dissolved the bicameral legislature and replaced it with a unicameral legislature of supporters. While his term was up in 1963, the ballot proceeded with his name on it, showing 0 in opposition. He “hesitantly” accepted a new term, not wanting to “undermine the will of the people.” With no opposition left, he rewrote Haiti’s Constitution—and its identity. The nation’s flag, once blue and red, now bore a bottom field as black as diri ak djon djon, a symbolic gesture steeped in his own vision of power.

The US under Kennedy, concerned with the growing anti-Western sentiment of the Haitian government and misallocation of foreign aid, moved to suspend all aid payments to the Haitian government. Duvalier welcomed this, portraying it as “punishment for being the sole leader to stand up to the colonial powers.” He very publicly placed a voodoo curse on Kennedy, and after the Kennedy assassination, claimed credit for it. People began to eat Diri ak Djon Djon, both as sustenance and a dirge for the nation they had lost.

The US stance towards Haiti would evolve as the world did. Cuba’s communist regime sparked fears of other Caribbean nations becoming hostile to the US, and the US begrudgingly accepted Duvalier as a buffer against communism. Haiti would begin receiving millions of dollars a year of US aid again, setting the stage for misappropriation, and also serving as a base for the US against Cuba. Duvalier would reinvent himself as a staunch anti-communist, using the Tonton Macoute to terrorize leftists throughout Haiti.

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier died in 1971, leaving behind a bloody legacy. An estimated 30,000 citizens were killed by the government during his rule. Control of the government passed to his 19-year-old son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. Unlike his father, Baby Doc had little interest in governing—he preferred to bask in wealth and excess, leaving the actual ruling to advisors deeply entrenched in foreign interests. He was initially seen as kinder and gentler, with foreign nations becoming more generous with foreign aid. Of course, corruption soon became undeniable—Baby Doc turned the country’s tobacco administration into his personal slush fund, with no oversight, no accountability, and no concern for governance.

Baby Doc dispensed with Voodoo mysticism, thawing the chilling effect of his father’s regime, but opposition grew, especially in the North, the home of the djon djon mushroom. Under U.S. pressure, he agreed to eradicate Haiti’s creole pigs (1978–1982) to prevent African swine fever, devastating rural farmers’ livelihoods in the name of “modernization.” His 1981 marriage to Michèle Bennett, a light-skinned mulatto, exposed the hypocrisy of the Duvaliers’ black nationalism, further fueling northern resentment.

On March 9, 1983, Pope John Paul II visited Haiti, declaring, “Things must change here.” The nation was ready to erupt. In Gonaïves—the northern city where the Haitian flag was adopted in 1803—protests began in 1985, with demonstrators raiding a food distribution warehouse, looting djon djon mushrooms among other supplies. The unrest spread nationwide, often fueled by communal meals of Diri Ak Djon Djon shared among protesters. By February 7, 1986, the military, seeing no allies left for Baby Doc, forced him to flee. That night, Haitians ate Diri Ak Djon Djon as a free people once again after nearly 30 years of Duvalier rule.

I found Diri ak Djon Djon to have a unique, woody flavor. Shrimp was a welcome addition, and the more epis in this dish, the better.

- Diri Ak Djon Djon Recipe

- Serves: 4

- Prep Time: 15 minutes

- Cook Time: 30 minutes

Total Time: 45 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1 cup dried Djon Djon mushrooms (or 2 oz, available at Caribbean markets or online)

- 2 cups long-grain white rice, rinsed

- 1/2 cup green peas, fresh or frozen

- 1 medium onion, finely chopped

- 2 garlic cloves, minced

- 2 tbsp Mushroom Rebel Epis (see below)

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 1 tsp fresh thyme leaves (or 1/2 tsp dried thyme)

- 1 tsp salt, or to taste

- 1/2 tsp black pepper, or to taste

- 4 cups hot water (for soaking Djon Djon)

Instructions:

- Place Djon Djon mushrooms in a bowl with 4 cups hot water. Soak for 30 minutes until water turns inky black. Strain through a fine mesh sieve or cheesecloth, reserving the liquid. Discard mushrooms or finely chop for texture (optional).

- In a large pot, heat olive oil over medium heat. Add onion and garlic; sauté until soft, about 3–4 minutes, stirring occasionally.

- Stir in Mushroom Rebel Epis, thyme, salt, and pepper; cook for 1 minute until fragrant.

- Add rinsed rice and green peas; stir to coat, about 2 minutes.

- Pour in 3 1/2 cups of the reserved Djon Djon liquid (top with water if needed). Bring to a boil, then reduce to low, cover, and simmer for 20–25 minutes until rice is tender and liquid is absorbed.

- Fluff with a fork and let rest, covered, for 5 minutes before serving.

Notes:

- Sourcing: Find Djon Djon at Caribbean markets or online. Substitute with 1 tbsp mushroom powder and 1 tsp black food coloring for color. Scotch bonnet powder in Epis adds subtle heat.

- Storage: Best fresh; refrigerate for 2 days, reheat with a splash of water.

- Vegetarian: Ensure Epis is meat-free; dish is naturally vegetarian.

- Mushroom Rebel Epis Recipe

- Description: A seasoning for Diri Ak Djon Djon with earthy depth.

Makes: About 1 cup

Ingredients:

- 1/2 green bell pepper, roughly chopped

- 1/4 onion, roughly chopped

- 2 garlic cloves, peeled

- 1/4 cup fresh parsley, chopped

- 1 scallion, chopped

- 1/8 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 1 sprig fresh thyme, leaves only

- 1 tbsp dried porcini mushroom powder (or finely ground dried shiitake)

- 1/4 cup lime juice

- 1/4 cup olive oil

- 1 tsp white vinegar

- 1 tsp salt

Instructions:

- In a blender, combine bell pepper, onion, garlic, parsley, scallion, Scotch bonnet powder, thyme, mushroom powder, and salt. Pulse until finely chopped, about 20 seconds.

- Add lime juice, olive oil, and vinegar. Blend into a coarse paste, about 10 seconds.

- Store in a sealed jar in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks. Use 2 tbsp for Diri Ak Djon Djon.

Pikliz: The Spicy Slaw of Austerity

Pikliz, a spicy form of slaw, came from French methods of preservation of vegetables brought to its colonies. However, it combined with available Haitian produce, like Scotch Bonnet Peppers, to form a unique slaw that is imbued with the flavors of the Caribbean. It has served as a cheap method of keeping food from spoiling for centuries, and a staple of the Haitian working class. More than preservation, Pikliz became a symbol of survival—a working-class staple whose fiery sting matched the fury of Haiti’s workers in the early 90s as they fought for their livelihoods.

Following Baby Doc Duvalier’s departure, a military government, the Conseil National du Gouvernement, remained in control of the country. There were many attempts to bring about democratic elections, attempts that ended in bloodshed and failure. In 1987, during the first attempt, dozens of inhabitants were shot in the capital by former Tonton Macoutes. In 1988, only 4% of the citizenry voted, and the elected president, Leslie Manigat, was soon overthrown.

During this era, a prominent critic of the government emerged. Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who, much like Oscar Romero in El Salvador, used his position as a priest to preach a liberation theology-tinged excoriation of both the Duvalier regime and the military government that followed. He would preach of a reclamation of Haiti by its poor and dispossessed, the need for liberation, and the corruption that plagued the country. From his humble neighborhood in Port-au-Prince, he built a movement from the ground up—founding an orphanage for street children, teaching them not just survival but democracy, and instilling the belief that Haiti’s poor could reclaim their future. Pikliz was a staple of the poor then, and having fresh batches always made, in addition to more substantial food, proved to be a lifesaver for Port-au-Prince’s youth.

Because of his prominence, he was the target of four different assassination attempts. The largest one, the St. Jean Bosco massacre on September 11, 1988, saw 100 Tonton Macoutes wearing red armbands forcing their way into his church while he was saying Sunday mass. Army troops and police stood by and watched as armed men attacked parishioners with machine guns and machetes. 13 people died. 77 were wounded. Jean-Bertrand went into hiding and was ordered to leave Haiti by his priestly order. He refused and was expelled. Expelled but undeterred, Aristide knew there was only one path forward—he would run for president, turning his faith into a belief in political revolution.

Against the weight of history, Aristide won 67% of the vote with his new party, the Lavalas Political Organization—Haiti’s first true democratic election, a resounding rejection of decades of dictatorship. The people saw it as a rejection of austerity politics as well, taking barrels of pikliz to the streets and protesting for higher wages. Jean-Bertrand’s agenda was nothing short of revolutionary, calling for shorter working days, higher pay, and attempts to reform the military and stop corruption. He lit a fire in Haiti’s working class but made powerful enemies as well.

Several months into his term, his popular reforms sent shockwaves throughout the country, bolstered by massive demonstrations in support in every section of the country. Often these demonstrators would have barrels of pikliz to show the impact of austerity upon the working class. Aristide dismantled the Tonton Macoute-era strongholds, stripping power from local warlords and bringing Haiti’s fractured law enforcement under a single system—one loyal to the people, not the old regime. He also would increase the minimum wage, establish a literacy program, and begin an investigation into human rights abuses.

At the end of 1991, the military overthrew Aristide and threw him into exile. A military regime was established, one whose extreme measures of oppression would have made Papa Doc Duvalier blush. A massive diaspora of Haitians left, with barrels of pikliz left fermenting in their homes as they struggled to escape.

The UN, Organization of American States, and US took note as Haiti descended into chaos. They would contact Jean-Bertrand Aristide and help return him to power with military action to finish out the remainder of his term. He would honor the constitution and stand down, not running for another uninterrupted term. Leaving office with unfinished promises, an economic meltdown, and interrupted by a coup, he saw the democracy he helped foster to be more important than ambition. By the time his successor took office, René Préval, people were still demonstrating, with pikliz in hand.

I am a big fan of slaw of all kinds. Pikliz has proven to be no exception. The sharp bite and spicy, tangy taste have proven to make it one of my favorites.

- Pikliz Recipe

- Serves: 8 (as a condiment)

- Prep Time: 15 minutes

- Rest Time: 24 hours

Total Time: 24 hours 15 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1/2 head green cabbage, shredded

- 1 large carrot, grated

- 1/2 medium onion, thinly sliced

- 1/4 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 1 cup white vinegar

- 1/2 cup lime juice

- 1 tbsp Holy Ghost Epis (see below)

- 1 tsp salt

- 1/2 tsp black pepper

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 tsp fresh thyme leaves (optional)

Instructions:

- In a large glass jar or bowl, combine cabbage, carrot, onion, Scotch bonnet powder, garlic, and thyme (if using).

- Add Holy Ghost Epis and toss to distribute evenly.

- In a small saucepan, heat vinegar, lime juice, salt, and pepper over medium heat until just simmering, about 2 minutes.

- Pour hot liquid over vegetables, ensuring they’re submerged. Let cool to room temperature, about 30 minutes.

- Seal jar or cover bowl and refrigerate for at least 24 hours (best after 2–3 days).

- Serve with Griot, shaking or stirring before serving.

Notes:

- Sourcing: Scotch bonnet powder adds concentrated heat; adjust quantity for spice level.

- Storage: Lasts up to 1 month in the refrigerator.

- Holy Ghost Epis Recipe

- Description: A liberation-inspired seasoning for Pikliz.

Makes: About 1 cup

Ingredients:

- 1/2 green bell pepper, roughly chopped

- 1/4 onion, roughly chopped

- 3 garlic cloves, peeled

- 1/4 cup fresh parsley, chopped

- 1 scallion, chopped

- 1/4 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 1 sprig fresh oregano, leaves only

- 1/4 cup lime juice

- 1/4 cup olive oil

- 1 tsp white vinegar

- 1 tsp salt

Instructions:

- In a blender, combine bell pepper, onion, garlic, parsley, scallion, Scotch bonnet powder, oregano, and salt. Pulse until finely chopped, about 20 seconds.

- Add lime juice, olive oil, and vinegar. Blend into a coarse paste, about 10 seconds.

- Store in a sealed jar in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks. Use 1 tbsp for Pikliz.

- Substitute:

If unavailable, mix 1 tsp minced garlic, 1 tsp lime juice, 1/2 tsp hot sauce, and 1 tsp dried oregano.

Salade de Betteraves: Flag Day Feast of Frenzy

Salade de Betteraves, or Salade Russe, is commonly a dish associated with Russia, first being made by a Belgian chef in Moscow. But, over years of being served in Haiti, it became something uniquely Haitian, replacing the creamy textures and taste with a more tangy taste associated with the Caribbean, and beets taking an extra spot of prominence. Its colors evoke the colors of the Haitian flag, and it’s often eaten at celebrations, especially Flag Day celebrations. But it is Flag Day 2004 we are most interested in today.

After Jean-Bertrand left the presidency in 1996, he quickly found himself at odds with his former protégé. René Préval embraced economic liberalization in the privatization-heavy 90s, securing foreign approval but alienating Haiti’s working class. Aristide, once his ally, became his sharpest critic. Aristide formed a new Fanmi Lavalas Party and would contest the presidency again in 2000, as Haiti’s constitution did not prohibit non-consecutive presidential terms.

From the outset, controversy plagued 2000’s elections. Haiti’s election authority changed the method of selecting members of the legislature. With the opposition boycotting, Aristide’s party dominated the polls, securing a staggering 90% victory. But in the West, the election was condemned—viewed not as a mandate, but as a crisis.

Aristide saw his landslide victory as a mandate for sweeping change—expanding education, improving healthcare, raising wages, and dismantling the military that had long been a tool of political repression. But as Haiti’s working class cheered, his enemies sharpened their knives. Aristide didn’t just challenge Haiti’s internal power structures—he took aim at France itself, demanding reparations for the centuries of slavery that had built its wealth. It was a direct challenge to the independence debt that had strangled Haiti for generations, and the global elite took notice.

The Flag Day ceremonies were jubilant in 2001, as the working class celebrated with extra Salade de Betteraves, full of hope for the future. However, the wealthier segments of Haiti’s population, military, foreign governments, and international financial institutions were less happy and less hopeful.

Aristide’s reforms gained momentum—Cuban doctors arrived, new schools rose, and Haiti’s working class saw glimpses of a future once denied to them. But progress breeds enemies. As change spread, so did fear among Haiti’s elite. The military weaponized fear, spreading the claim that Aristide’s reforms were a smokescreen for street gangs enforcing his rule. The message spread, echoed by Haiti’s elite and amplified in the halls of Western power.

The ground beneath Aristide shifted. In the North, gangs that had once operated in the shadows now moved against him, claiming retribution for his government’s targeting of their leaders. Their name—the Cannibal Army—made their intent clear: they would feast on the ruins of the state. They took the city of Gonaïves and linked up with far-right paramilitary members, former Duvalier-era Tonton Macoute, and former military that had participated in the first coup against Aristide in 1991 and had been exiled to the Dominican Republic.

Now, the paramilitaries had a lifeline—trained by the Dominican Republic, and almost certainly linked to American and French intelligence. The shadow of intervention grew darker, and Aristide’s government was running out of time. The newly christened National Revolutionary Front for the Liberation and Reconstruction of Haiti would engage in open guerilla warfare against Aristide’s government. It wouldn’t be long before they were knocking on the gates of the capital.

In February 2004, Aristide—isolated and surrounded by forces beyond his control—was pressured into departure. To this day, he maintains it was a US-led coup. Washington insists it was an internal power struggle. The truth, buried in diplomatic cables and backroom deals, remains contested. Either way, three days later, UN peacekeepers would enter the country and ensure the presidency passed to the next in line of succession: Boniface Alexandre, the Chief Justice.

The country would soon erupt into the largest mass protests it had ever seen. These culminated with Flag Day, May 18, 2004, when Port-au-Prince erupted into a massive protest, with marchers, fresh from their Salade de Betteraves, attempting to defend the legacy of their flag and revolution. The jury is still out on that.

Now, as to the food. This salad is incredibly easy to make and quite flavorful. I’m a big fan!

- Salade de Betteraves Recipe

- Serves: 6

- Prep Time: 30 minutes

- Chilling Time: 1–3 hours

Total Time: 1 hour 30 minutes to 3 hours 30 minutes

Ingredients:

- 2 lbs russet potatoes, peeled and cubed (1-inch pieces)

- 1 cup carrots, diced (1/4-inch pieces)

- 1 cup cooked beets, diced (1/4-inch pieces, about 2 medium beets)

- 1 cup green peas, fresh or frozen

- 3 large eggs, hard-boiled and chopped

- 1 cup mayonnaise (or vegan mayo for plant-based)

- 1 tbsp Dijon mustard

- 2 tbsp apple cider vinegar

- 1/4 cup green onions, finely chopped

- 1 tbsp lime juice

- 1 tbsp Flag Feast Epis (see below)

- 1/2 tsp salt, or to taste

- 1/2 tsp black pepper, or to taste

- 1/2 cup chayote, diced (optional)

- 2 tbsp fresh parsley, chopped (for garnish)

- Hot sauce (optional, to taste)

Instructions:

- If using raw beets, boil separately in a small pot for 30 minutes until tender; drain, cool, and dice. Alternatively, use pre-cooked beets.

- In a large pot, bring salted water to a boil. Add potatoes and carrots; boil 12–15 minutes until tender but firm. Add peas in the last 2 minutes. Drain and cool to room temperature, about 15 minutes.

- In a large bowl, combine cooled potatoes, carrots, beets, peas, eggs, and chayote (if using). Add mayonnaise, mustard, vinegar, green onions, lime juice, Flag Feast Epis, salt, pepper, and hot sauce (if using). Gently toss to coat.

- Cover and refrigerate for at least 1 hour to meld flavors, preferably 2–3 hours.

- Before serving, garnish with parsley. Serve chilled.

Notes:

- Sourcing: Scotch bonnet powder in Epis adds concentrated heat; adjust to taste.

- Storage: Refrigerate for up to 3 days.

- Cultural Note: Bright with beets and Flag Feast Epis’s lime-cilantro tang, this salad united 2004’s protesters, a festive fist for Flag Day 2025.

- Flag Feast Epis Recipe

- Description: A vibrant seasoning for Salade de Betteraves.

Makes: About 1 cup

Ingredients:

- 1/2 red bell pepper, roughly chopped

- 1/2 green bell pepper, roughly chopped

- 1/4 onion, roughly chopped

- 2 garlic cloves, peeled

- 1/4 cup fresh cilantro, chopped

- 1 scallion, chopped

- 1/8 tsp Scotch bonnet powder

- 1 sprig fresh thyme, leaves only

- 1/4 cup lime juice

- 1/4 cup olive oil

- 1 tsp apple cider vinegar

- 1 tsp salt

Instructions:

- In a blender, combine bell peppers, onion, garlic, cilantro, scallion, Scotch bonnet powder, thyme, and salt. Pulse until finely chopped, about 20 seconds.

- Add lime juice, olive oil, and vinegar. Blend into a coarse paste, about 10 seconds.

- Store in a sealed jar in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks. Use 1 tbsp for Salade de Betteraves.

- Substitute:

If unavailable, mix 1 tsp minced garlic, 1 tsp lime juice, 1/2 tsp hot sauce, and 1 tbsp cilantro.

Comments

Post a Comment